1.“About half way between West Egg and New York the motor road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile, so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes—a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens; where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and, finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air.” – The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

“T.J. Eckleberg from The Great Gatsby”

Today, strip malls are a great American tradition. They are a pillar of Suburban Sprawl and the face of American architecture. Patrick Gallagher of the American Bar Association describes Suburban Sprawl as “uncontrolled development that expands outward from city centers and consumes otherwise undeveloped land.” (219). Strip malls and small shopping centers consume the journey between urban districts and affluent suburban neighborhoods. They create a wasteland of passerby’s and short-term renters. F. Scott Fitzgerald provides an excellent description and foreshadow in The Great Gatsby’s Valley of Ashes. Since the 1920s strip malls have defined the American aesthetic and provided a platform for the impediment of upward mobility. As a result, the demise of the American Dream can be traced to the introduction of small-scale shopping centers.

2. “Modernism is about space. Postmodernism is about communication. You should do what turns you on.” –Robert Venturi

“Strip Mall, 1960”

Baltimore, 1907. Pilot shopping centers were introduced in Baltimore as social spaces for community engagement. By 1931 these shopping centers began to be built deliberately beyond walking distance, begging the need for cars. The Highland Park Shopping Village in Dallas, TX began this automobile-dependent economy. Richard Feinberg of Purdue University explains “Whatever and wherever its start, the phenomenal growth and development of shopping centers naturally followed the migration of population out from the cities and paralleled the growth of the use of the automobile.” (426). This phenomenon is referred to as Suburban Sprawl and defined the spatiality and subsequent social structure of America. As the nation moved into the 20th century their homes became bigger, their cars faster, and their neighbors whiter. In this sense strip malls became a necessary redistricting mechanism, which had profound ramifications on group identity.

3. “In the 1954 Internal Revenue Code, a Republican Congress changed forty-year, straight-line depreciation for buildings to permit ‘accelerated depreciation’ of greenfield income-producing property in seven years. By enabling owners to depreciate or write off the value of a building in such a short time, the law created a gigantic hidden subsidy for the developers of cheap new commercial buildings located on strips.” – Dolores Hayden, Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000

Strip malls emerged and took hold of Suburban America as white families began their “sprawl” beyond city lines. Following World War II city planners deliberately built these quasi-malls in order to offset the formerly rural suburban towns. Strip malls created a sense of purpose for white suburban dwellers. Residents hoped their new neighborhoods would become a hybrid between urban and rural neighborhoods. Moving beyond city limits they yearned for spacious, crime-free, demographically homogenous landscapes to raise their children. However, many families were weary to settle too far beyond a sense of civilization. The popularization and affordability of automobiles allowed middle-class white families access to out-of-reach areas. City planners jumped at this opportunity by creating small shopping centers just far enough out of site to avoid obstruction of the spacious landscape.

4. “It was very unusual to employ prettiness as part of a building.” –Robert Venturi

Strip malls are notoriously ugly. However, wealthy, well-kempt neighborhoods across America depend on strip malls in order to maintain their status. This paradox stems from the functionality of strip malls; their scale and semi-accessibility allow them to be near wealthy suburbs, but just far enough out of site as to not diminish status. Jane Gross defines this functionality as allowing suburban dwellers to “have our cake and eat it too”. Gross uses Westchester County as her primary example. Westchester includes many of these affluent, well-kempt neighborhoods, however, it also includes 10-miles of consecutive strip malls. The two are able to coexist, and even flourish simultaneously due to their extreme concentration.

5. “It was clear that there needed to be a movement for the architects of the middle ground, once the elite became inaccessible.” –Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, architect, Seaside, FL.

“Housewives shopping, 1950”

Whoever said housewives don’t do anything was seriously disturbed. Strip malls acted like a kryptonite for these white, middle-class housewives, and they still do. The end of World War II diminished female roles in society. As men returned home, women were no longer required to pick up their slack on the home front. As a result, most women quit their industrial jobs, married, and settled down. Bored at home and searching for purpose while their husbands went to work, housewives took to these shopping centers. As shopping centers moved out of cities, so did housewives and their families. In fact, housewives acted as the “invisible hand” behind the so-called “uncontrolled development”. For this reason, housewives deserve far more recognition for their contributions to American national identity as well as the many ramifications resulting from Suburban Sprawl.

6. “Modern architects contradict themselves when they support functionalism and megastructure. They do not recognize the image of the processed city when they see it on the Strip, because it is both too familiar and too different from what they have been trained to accept.” –Robert Venturi

“Randy’s Donuts, Los Angelos, California”

Strip malls can teach us a lot about urban planning. Architects began studying strip mall culture during the post-modern era. By this time strip malls were an established feature of American architecture and worthy of deeper study. Famed architect Robert Venturi of the University of Pennsylvania and founder of the Philadelphia School, a philosophy of post-modernism in America, devoted his studies to strip mall architecture. With the help of his students he used the Las Vegas Strip as the focal point of his study. The Las Vegas Strip exemplifies how strip malls have come to established cultural dependencies on spatial constructions. Venturi introduced the “Duck v. Decorated Shed” theory as an exploration of the use of signs over space.

“Robert Venturi’s Duck v. Decorated Shed model”

Venturi advocates for structures that exemplify their intended use through their shape and structure, also known as a the “duck” approach. Signs dominate the Las Vegas Strip telling drivers and passerbies where to go and what they need. Venturi explains that strip mall parking lots are essential to the workings of this phenomenon. Strip malls do not offer window displays; therefore, they depend upon signs to lure shoppers into stores. These signs and advertisements are more easily read as shoppers approach their parking lots, which play host to many stores allowing choices. Choices increase a driver’s likelihood to approach a shopping center.

7. “Cars moving through neighborhoods are only borrowing the public space of the dwellings facing the street.” –Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk architect, Seaside, FL

“Las Vegas Strip, Nevada”

Strip malls invented U-turns. Busy roads alongside strip mall-ed areas, such as along the Las Vegas Strip, developed U-turns in order to allow drivers to easily return to a center they may have driven past. Storeowners and investors lobbied for the current turning systems in order to aid their own economic growth. Venturi explains, “the continuous highway itself and its systems for turning are absolutely consistent.

“Las Vegas Strip”

The medium strip accommodates the U-turns necessary to a vehicular promenade for casino crawlers as well as left turns onto the local streets pattern that the Strip intersects. The curbing allows for frequent right turns for casinos and other commercial enterprises and eases the difficult transition from highway to parking.”. In other words, the U-turn was invented to propel strip mall culture.

8. “Strip malls are history.” –Jeff Bezos CEO, Amazon

“Midlothian Turnpike, Richmond, Virginia”

There are many negative impacts of strip malls on the population, including air and water quality, and urban decline. Sprawl propelled the automobile industry, and, with it atmospheric carbon emissions. With the population influx to rural areas, Sprawl begged the need to increase water consumption. This meant a higher dependency on ground-water digging. However, by implementing pavement suburban areas are not conducive to ground-water digging. As a result, water must be transported into suburbs. Most concerning is the abandonment of smaller urban areas. Sprawl diminished municipal tax bases by removing wealthy residents from urban areas. This problem persists today.

Richard A. Feinberg and Jennifer Meoli (1991) ,”A Brief History of the Mall”, in NA – Advances in Consumer Research Volume 18, eds. Rebecca H. Holman and Michael R. Solomon, Provo, UT : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 426-427.

Gross, J. (2001, Mar 31). Westchester’s 10-mile strip mall. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/docview/92137419?accountid=14405

Gallagher, Patrick. “The Environmental, Social, and Cultural Impacts of Sprawl.” Natural Resources & Environment, vol. 15, no. 4, 2001, pp. 219–267. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40924406.

Venturi, Robert, et al. Learning from Las Vegas : The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form. Rev. ed. ed., MIT Press, 1977.

Venturi, Robert, and Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.). Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. Museum of Modern Art, 1966.

As the American Revolution approached, peo

As the American Revolution approached, peo

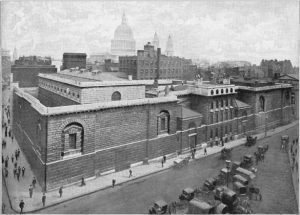

In 1797, New York State built its first penitentiary: Newgate Prison in Greenwich Village. This institution only remained open for 27 years, as several design flaws led to its ultimate destruction. The idea to move away from corporal punishment because of its violent nature was significantly undermined by the presence of violence for several reasons, one of which were cell designs that placed eight people in one cell to sleep. Prisons were justified as a place where human lives could be rehabilitated to prevent future criminal activity. The construction of Newgate and subsequent prisons call into the question the possibility to achieve that goal given the environment that results from the physical design of these institutions.

In 1797, New York State built its first penitentiary: Newgate Prison in Greenwich Village. This institution only remained open for 27 years, as several design flaws led to its ultimate destruction. The idea to move away from corporal punishment because of its violent nature was significantly undermined by the presence of violence for several reasons, one of which were cell designs that placed eight people in one cell to sleep. Prisons were justified as a place where human lives could be rehabilitated to prevent future criminal activity. The construction of Newgate and subsequent prisons call into the question the possibility to achieve that goal given the environment that results from the physical design of these institutions. Eastern State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania was a prison built in the context of the the “Auburn system.” A central idea behind the physical designs of prions fitting this model encourage separation/isolation as a form of rehabilitation, where the only “services” provided was a daily visit from the Warden. There were many complaints about cell designs, which aimed to minimize threats to the guards, yet it made it extremely difficult to pass food and transport inmates, presenting various human rights concerns.

Eastern State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania was a prison built in the context of the the “Auburn system.” A central idea behind the physical designs of prions fitting this model encourage separation/isolation as a form of rehabilitation, where the only “services” provided was a daily visit from the Warden. There were many complaints about cell designs, which aimed to minimize threats to the guards, yet it made it extremely difficult to pass food and transport inmates, presenting various human rights concerns. During the Civil War and Antebellum period, ideas about punishment shifted as well as the reality of overcrowding in prisons. The Jackson Era is well known for its negative influence on prisons, especially in regards to the physical deterioration the physical structures endured, which exacerbated conditions for people within the prisons. Several strategies – now viewed as cruel – were implemented during this time period, such as solitary confinement, straightjackets, the iron cage, etc.

During the Civil War and Antebellum period, ideas about punishment shifted as well as the reality of overcrowding in prisons. The Jackson Era is well known for its negative influence on prisons, especially in regards to the physical deterioration the physical structures endured, which exacerbated conditions for people within the prisons. Several strategies – now viewed as cruel – were implemented during this time period, such as solitary confinement, straightjackets, the iron cage, etc. While most people associate prison as a place where violent criminals are sent, this institution has been used as a tool to punish people for uncollected debt. The term “debtors prison” captures the ability of the state to punish people for unpaid fines through imprisonment. As an institution, prisons promote capitalism through the profits gained through privatization as well as the ability to use it as a tool for those who do not have the ability to pay a fine, child support, garnishments, etc.

While most people associate prison as a place where violent criminals are sent, this institution has been used as a tool to punish people for uncollected debt. The term “debtors prison” captures the ability of the state to punish people for unpaid fines through imprisonment. As an institution, prisons promote capitalism through the profits gained through privatization as well as the ability to use it as a tool for those who do not have the ability to pay a fine, child support, garnishments, etc. Gender identity within the prison context has become increasingly more known to people as women – especially women of color – started facing incarceration at higher rates during mass incarceration. Moreover, prisons are separated based upon a gender binary, which often forces people in the trans community to be incarcerated based on their sex rather than gender identity, which often creates violently dangerous situations.

Gender identity within the prison context has become increasingly more known to people as women – especially women of color – started facing incarceration at higher rates during mass incarceration. Moreover, prisons are separated based upon a gender binary, which often forces people in the trans community to be incarcerated based on their sex rather than gender identity, which often creates violently dangerous situations. One of the most controversial prisons in existence today is arguably Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp, which is a U.S naval base. A large part of the controversy is two-fold. On one hand, it is well known that people often end up in Guantanamo Bay for long periods of time without a trial, eliminating any presumption of innocence and directly contradicting the U.S Constitution. On the other hand, a huge focus on the use of torture against people being detained is repeatedly cited as a reason for advocating for the prison to be closed.

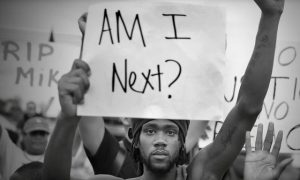

One of the most controversial prisons in existence today is arguably Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp, which is a U.S naval base. A large part of the controversy is two-fold. On one hand, it is well known that people often end up in Guantanamo Bay for long periods of time without a trial, eliminating any presumption of innocence and directly contradicting the U.S Constitution. On the other hand, a huge focus on the use of torture against people being detained is repeatedly cited as a reason for advocating for the prison to be closed. Mass incarceration can be understood as the system by which people of color are subjected to disparate rates of policing, arrests, and imprisonment. Several books and even documentaries outline the inherent racial bias of the U.S criminal justice system, which can be understood through various institutions and laws. Today, the privatization of prisons – in the context of the prison-industrial complex – has led to a system where economic profit drives incarceration rates, leading to the connection of mass incarceration being the new form of enslavement.

Mass incarceration can be understood as the system by which people of color are subjected to disparate rates of policing, arrests, and imprisonment. Several books and even documentaries outline the inherent racial bias of the U.S criminal justice system, which can be understood through various institutions and laws. Today, the privatization of prisons – in the context of the prison-industrial complex – has led to a system where economic profit drives incarceration rates, leading to the connection of mass incarceration being the new form of enslavement.

to gather. Similar to this, why should any historical community need to change? This community specifically represents hope and change, and should continue to do so in order to shine a light for those who feel disenfranchised within the LGBTQ community.

to gather. Similar to this, why should any historical community need to change? This community specifically represents hope and change, and should continue to do so in order to shine a light for those who feel disenfranchised within the LGBTQ community.

This is seen throughout the south and even the midwest, people wanting to ditch city lifestyle to live in a mire quaint town, that still seems to be a tourist destination. “Every year, thousands of working-age people move from big cities to smaller cities, often in scenic areas, that are better known for drawing seasonal tourists and retirees.” [10]

This is seen throughout the south and even the midwest, people wanting to ditch city lifestyle to live in a mire quaint town, that still seems to be a tourist destination. “Every year, thousands of working-age people move from big cities to smaller cities, often in scenic areas, that are better known for drawing seasonal tourists and retirees.” [10] ‘

‘