Background

Just over two decades ago, in 1989, Elizabeth Horton Sheff and a coalition of plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against Connecticut’s then-governor, William O’Neill, calling attention to the stark segregation and inequality that characterized Hartford Area schools at the time. Now, twenty-six years later, almost half of the students in Connecticut’s capital city attend integrated schools.[i] When plaintiffs returned to the courtroom in 2003, they walked out with a new settlement that set even higher standards for racial integration within schools. In addition to expanding participation in the “Open Choice” system (previously known as “Project Concern”), this legislation called for the expansion of public charters and themed magnet schools in the Hartford Area. Connecticut’s system has been hugely successful in its attempts to promote racial integration within schools: In a recent Civil Rights Project report, Gary Orfield, a Distinguished Professor of Education, Law and Political Science and Urban Planning at UCLA, referred to it as “the only successful effort to produce a new legal framework to deal with the reality of metropolitan segregation.”[ii],[iii] Despite this undeniable progress, though, the system has been far from inclusive of the state’s large population of nonnative English speakers and has a long way to go before reaching its goal of equal educational opportunity for all students.[iv],[v] In order for English Language Learners (ELL) to be fairly represented in Connecticut’s choice schools, two things must happen. First and foremost, the state must implement recommended policy changes designed to address the insufficiency of bilingual education programs in these schools. Secondly, they should support the establishment of new dual-language magnet schools.

ELL Disparity in Choice Schools: What the Numbers Say

The number of English Language Learners in Connecticut is immense, and it is growing rapidly. In 2011-2012, over 30,000 students were considered to be ELL (and it is likely that this is an underestimate), making up 5.4% of the state’s total student population.[vi] Despite their large presence, ELL students are severely underrepresented in Connecticut’s public choice schools (specifically in magnet, charter and technical schools). According to the Choice Watch Report released in 2014 by policy analysts Robert Cotto and Kenny Feder, in the 2011-2012 school year, 76% of public charters, 64% of magnets, and 56% of technical schools in the Greater Hartford Area (GHA) had substantially lower enrollment percentages of ELL students than the local, traditional public schools in their districts.[vii] Unfortunately, choice schools have not become any more inclusive in the years since their report. These schools still enroll significantly lower percentages of ELL students than the traditional public schools in their respective districts.

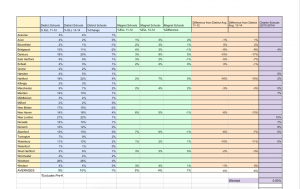

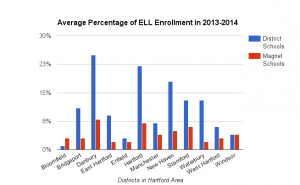

ELL Enrollment in Magnet Schools, by District (2013-2014)

When our Choice Seminar at Wesleyan updated the Choice Watch Report with 2013-2014 data provided to us by the CT State Department of Education (based on 13 of the 28 GHA districts – as much data as was available), we found that ELL students are still underrepresented, and especially so in magnet schools. ELL students are no more represented in magnet schools than they were two years ago, and in some cases, they are less so. Currently, the average ELL student-composition across the GHA is 10% for district schools, but only 4% for magnets. To identify districts that did a better job in encouraging ELL enrollment, it is most useful to look at the relative proportions within a particular district, rather than looking at the GHA as a whole. Danbury (25%), Hartford (22%), New London (22%) and Windham (26%) district schools enroll the highest percentages of ELL students. Danbury magnet schools, however, enroll 17% fewer ELL students than their district counterparts; this represents the largest enrollment gap in the GHA.[viii] Charter and technical schools also tend to under-enroll ELL students. The average composition of ELL students among Bridgeport’s four public charter schools is only 4%.[ix]

Solution #1: Policy Changes

This past January, a group of concerned stakeholders including teachers, administrators, and members of the Latino and Asian communities held a forum to address the lack of resources for bilingual education. Luckily, a few legislators listened to their suggestions and worked with them to write what because known as House Bill 6835, “An Act Concerning English Language Learners.”[xiii] Aiming to better educational opportunities for ELL students in Connecticut, the original bill proposed changes to existing policies. Two recommendations, in particular, are ones that, if passed, could potentially have a significant and positive impact on the under enrollment of ELL students at choice schools.

As it stands, the Bilingual Education Statute (Section 10-17e-j) dictates that only schools with twenty or more ELL students must offer a program of bilingual education. [xiv] Furthermore, those twenty students have to speak the same foreign language. [xiv] On top of that, to say bilingual education is loosely defined in the statutes would be a gross understatement. H.B. 6835’s originally called for a decrease in this threshold, from twenty students to six. Based on 2013-2014 enrollment data, this decreased minimum would lead to the new bilingual education programs in at least forty additional choice schools in the Hartford Area. Soon after the stakeholders met, the Joint Education Commission held a public hearing, at which much dissent was expressed over the proposed amendments, in part due to financial concerns. Interestingly enough, Connecticut only spends a mere $1.9 million dollars on over 30,000 ELL students every year: a number that comes out to around $50-$60 per student.[xv] Nonetheless, in the resulting substitution bill, the proposed amendment to lower the twenty-person minimum had been thrown out.

The Connecticut Statute for Education also limits the amount of time that a student is allowed to spend in a bilingual education program to just thirty months – If the student is within 30 months of high school graduation, they are not eligible for the services at all. A second, important feature of H.B. 6835, that did make it into the substitution bill, was a two-fold increase in this time frame, from thirty to sixty months. Just last week, on April 29th, the Appropriations Committee of the Connecticut General Assembly voted 36 to 20 in favor of the Joint Education Committee’s substitution bill. [xvi] H.B. 6835 still has a long way to go – it must pass through both House and Senate before its fate is sealed.

Solution #2: Dual Language Magnet Schools

According to Cotto and Feder’s 2012 Report, in the 2011-2012 school year, just under 50,000 students were enrolled in one of Connecticut’s choice programs – the majority of these students attended one of 63 interdistrict magnet schools.[xvii] In Connecticut, it’s easy enough to find a magnet school with just about any theme – there are magnet schools for arts, for aerospace and engineering, and for global citizenship. In New Haven, there is a very special magnet school called the John C. Daniels School (JDS). JDS is a dual-language immersion school, and with 19% of its students being ELL, a proportion one percentage point higher than the district average and more than twice that of any other interdistrict magnet school in New Haven.[xviii] So, if only 19% of students at JDS are ELL, then who are the other 81%? They are native English speakers, and they have chosen to go to JDS to learn Spanish. At JDS, half of classes are taught in English, and half are taught in Spanish. Then, in middle school, students can elect to take either Mandarin or continue on with Spanish.[xix]

With the creation of more bilingual education schools comes the problem of staffing. Some consider the state’s stringent certification requirements for bilingual education teachers to be one of the biggest barriers to serving the needs of the state’s large (and growing) ELL student population. To become certified in bilingual education, a teacher must go to through a fifth year of schooling. However, once certified, they are not paid any more than regular teachers. The state also does not recognize out-of-state certification – only teachers who received their bilingual education certificates in the state of Connecticut are eligible to teach. A bill that is currently on the senate calendar, Bill 1102, addresses these stipulations. If it passes, establishing more of these themed-magnets will become a more feasible prospect: more teachers mean more programs in more schools, and more options for ELL students.

Looking Forward

Both key policy changes originally proposed in H.B. 6835 could have made many more schools practical choices for ELL students. The suggestion for the extension of the time maximum for bilingual education programs that still remains in the bill’s text is not an insignificant one. Not only could it enhance learning opportunities for students already enrolled in these programs, but it could also serve as a potential justification for the creation of new, dual-language magnet schools, if their documented success will not suffice as persuasion, since they would be providing dual-language instruction over four-or-more years. Connecticut’s choice schools should be more than just options for ELL students: they should be sensible options, at the very least. I am neither a policy analyst nor an expert in education, but I do believe in evidence, and right now the evidence suggests that something must be done.

[i] Rabe Thomas, J. (2013, November 26). Nearly half the students from Hartford now attend integrated schools. Retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://ctmirror.org/nearly-half students-hartford-now-attend-integrated-schools/.

[ii] http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/connecticut-school-integration-moving-forward-as-the-northeast-retreats/orfield-ee-connecticut-school-integration-2015.pdf.

[iii] Rabe Thomas, J. (2013, November 26). Nearly half the students from Hartford now attend integrated schools. Retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://ctmirror.org/nearly-half students-hartford-now-attend-integrated-schools/.

[iv] See, Plurality Opinion of the State Supreme Court, Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding vs. Rell. March, 2009. Available at http://ccjef.org/litigation.

[v] How and Miller. Inequality in ELL-Enrollment at District versus Magnet Schools in the Greater Hartford Area. March, 2015. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1n0kDYiXIWSq17hSQl5aW8ecmKwZb6J-3PhHsdfHkffg/edit

[vi] Hartford Public Schools. Two-Way Language Program Feasibility Study, January 3, 2013. http://www.achievehartford.org/upload/files/DualLanguageDiscussion—20130124123318926.pdf.

[vii] Cotto, R. & Feder, K. (2014). Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs, (p. 17). Connecticut Voices for Children. New Haven, CT.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Miller, C. & How, H. (2015, March 6). “Inequality in ELL-Enrollment at District versus Magnet Schools in the Greater Hartford Area. Available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1n0kDYiXIWSq17hSQl5aW8ecmKwZb6J-3PhHsdfHkffg/edit.

[x] Zimmerman, E. (Director) (2015, February 25). Testimony before the Education Committee on Proposed S.B. No. 944 and H.B. 6835. Commission on Children. Lecture conducted from State of Connecticut General Assembly, Hartford, Connecticut. Available at http://www.cga.ct.gov/2015/eddata/tmy/2015SB-00944-R000225-Elaine%20Zimmerman,%20CT%20Commission%20on%20Children-TMY.PDF.

[xi] ConnCan: Connecticut Maintains Worst-in-the-Nation Achievement Gap. (2013, November 8). Retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://www.conncan.org/media-room/press-releases/2013-11-conncan-connecticut-maintains-worst-in-the-nation-ac.

[xii] Boesner, B. (2013, November 7). 2013 NAEP Snapshot [PDF document]. Retrieved from http://webiva-downton.s3.amazonaws.com/696/f8/4/1276/4/2013_ConnCAN_NAEP_Snapshot.pdf.

[xv] Rodriguez, O. (2015, May 1). Background Information on H.B. 6835 [Telephone interview].

[xvi] Appropriations Committee – Vote Tally Sheet. (2015, April 29). Retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://www.cga.ct.gov/2015/TS/H/2015HB-06835-R00APP-CV33-TS.htm.

[xvii] Cotto, R. & Feder, K. (2014). Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs. Connecticut Voices for Children. New Haven, CT.

[xviii] MacDonald, A. (2015, March 6). “Angus’s Exercise D.” Available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1CPD_xgiWQFqSIPHbyRDXEHWRZ_ti61Qv8P-FhuXRxwE/edit.

[xx] John C. Daniels School Test Scores – New Haven County, CT. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2015, from http://www.realtor.com/local/John-C-Daniels-School_New-Haven_New-Haven-County_CT/test-scores

[xxi] Image retrieved from http://childcarecenter.us/static/images/providers/9/1022289/129453-John-Daniels.png.