Hartford lawyer and Democratic delegate Simon Bernstein stuck out from his political peers at the 1965 Connecticut Constitutional Convention. While the Democratic and Republican chairmen of the time were entrenched in a debate over the state’s unequal political representation system, Bernstein dared to dream a little bigger (Bernstein interview by Campbell 10). As a member of the Bloomfield Board of Education, Bernstein recognized that in 1965, Connecticut was the only state that did not guarantee its citizens a constitutional right to an education and thus decided to draft a new amendment to address this problem (9, 11). After days of being ignored by his Democratic Party superiors and then finally threatening to confront the media about his concerns, Bernstein’s request was met. Delegates at the 1965 Connecticut Constitutional Convention passed Bernstein’s amendment which guarantees free public education to every child, setting the stage for a series of prominent educational lawsuits, including Horton v. Meskill (1970), Sheff v. O’Neill (1989), and Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding (CCJEF) v. Rell (2005) (Bernstein interview by Campbell 11, 1; “CCJEF v. Rell Overview”).

The Man Behind the Amendment

Bernstein was born on January 17, 1913, in Hartford, Connecticut (Bernstein interview by Campbell 13; “Simon Bernstein). After graduating from Trinity College and Harvard Law School, he began his political career in Hartford as a lawyer and democratic alderman (Bernstein interview by Campbell 1, 13). During his time in Hartford, Bernstein served on the city’s Finance Committee and also actively participated in the 1940s Zionist movement, a political effort that sought to encourage local lawmakers to support Israel’s fight for its own state (Bernstein interview by Campbell 9; Bernstein Interview by Zaiman 3). In 1950, Bernstein moved to Bloomfield and was elected to the Bloomfield Board of Education (Bernstein interview by Campbell 1, 9).

In all of his political efforts, Bernstein proved he was not afraid to confront difficult issues that others were hesitant to address. For example, in 1947, Bernstein took on a legal case involving a racially restrictive covenant, a term used to describe real estate agreements that prohibit people of a specific race from occupying a piece of land. This covenant, in particular, limited a property sale in the West Hartford area to “non-Semitic persons of the Caucasian race” (Bernstein interview by Campbell 4). The Hartford Courant published an article about Bernstein on March 28, 1947, which wrote that Bernstein felt the covenant’s racially specific language was “against public policy” (“Bernstein Seeks End” 21). Bernstein eventually managed to get this phrasing erased from the original property agreement, making him the first person in Connecticut to successfully address a legal case of this kind (Bernstein interview by Campbell 8).

The Creation and Impact of the Education Amendment

One of the reasons why Bernstein’s peers at the 1965 Connecticut Constitutional Convention attempted to stifle his enthusiasm about an education amendment was because they were focused on only one task: revising the state’s system of political representation. Connecticut’s representation system needed to be fixed because of the 1964 United States Supreme Court ruling in Reynolds v. Sims (Collier 593). The Court found that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause requires state legislatures to apportion representatives based on each district’s population to ensure that all citizens are equally represented (“Reynolds v. Sims”). This “one man, one vote” law thus made Connecticut’s system – two representatives for every district – unconstitutional (Collier 591).

Because the sole purpose of the Convention was to align Connecticut’s representation system with Reynolds v. Sims, John Bailey, the influential and Democratic chairman, had no interest in seeing any proposals regarding schools (Collier 593). However, this did not stop Bernstein from voicing his concerns about Connecticut’s lack of a constitutional guarantee to education: “I was enough of a history student of law, a lawyer, to know that once a convention is called for the state or national, nothing is irrelevant,” Bernstein stated in an oral interview (Bernstein interview by Campbell 10). Rather than accept the legislature’s pre-planned agenda, Bernstein chose to challenge his political superiors.

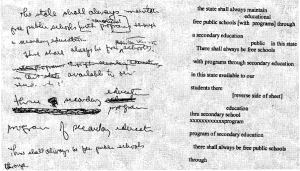

In order to get the legislature’s attention, Bernstein repeatedly asked Bailey to consider his proposal and also threatened to discuss his frustration with the media. In the end, it was this threat that got Bernstein what he wanted: Bailey granted Bernstein a meager five minutes to draft a proposal in an effort to quickly return to the discussion on political representation. Bernstein’s amendment, which he scribbled onto a scrap of paper in order to make his five-minute deadline, is general because Bernstein believed the language of the Constitution should reflect overall principles and ideas (Bernstein interview by Campbell 11). It states that, “There shall always be free public elementary and secondary schools in the state. The general assembly shall implement this principle by appropriate legislation” (Collier 591).

Although the world “equal” is not explicitly written in the amendment, its inference has been used as a foundation for nationally recognized educational inequality lawsuits such as Horton v. Meskill (1970), Sheff v. O’Neill (1989), and Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding (CCJEF) v. Rell (2005) (Bernstein interview by Campbell 1; Collier 594; “CCJEF v. Rell Overview”). At the time of Horton v. Meskill, Connecticut supplied school districts with $250 per child, forcing states to rely heavily on local property taxes for additional funding. The Horton plaintiffs used Bernstein’s amendment to argue that this system was unconstitutional because it meant educational quality varied considerably from poorer to wealthier towns (Eaton 90-91). Sheff v. O’Neill used Bernstein’s amendment to prove that the extreme racial, ethnic, and economic isolation of the Hartford school district left its schoolchildren, and other suburban schoolchildren, with an insufficient education that the state was required to remedy (“Sheff v. O’Neill”). The CCJEF v. Rell lawsuit used the 1965 Educational Amendment to argue that Connecticut’s system for funding public schools is not only inadequate, but also disproportionately harms minority schoolchildren and their ability to participate in the democratic process, thrive in college, and reap the monetary rewards of intellectual success (“CCJEF v. Rell Overview”; “CCJEF v. Rell” by The Lawyers Committee).

After his years as a laywer, Bernstein served as a Connecticut Superior Court Judge for 27 years. He passed away on January 17, 2013 at his home in Sarasota, Florida at the age of 100 (“Simon Bernstein”). His contribution to Connecticut lives on through the 1965 educational amendment that continues to serve as a foundation for educational inequality lawsuits throughout the state.

Works Cited

- “Bernstein Seeks End of Restrictive Clauses.” The Hartford Courant (1923-1987): 21. Mar 28 1947. ProQuest. Web. 5 Oct. 2013.

- Bernstein, Simon. Interview by Jack Zaiman. Greater Hartford Jewish Historical Society Oral History Collection. Greater Hartford Jewish Historical Society, 1971. Web. 6 Oct 2013.

- Bernstein, Simon. Interview by Katie Campbell. “Oral History Interview on Connecticut Civil Rights.” Trinity College Digital Repository. Trinity College, 2011. Web. 4 Oct 2013.

- “CCJEF v. Rell.” The Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, n.d. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. <www.lawyerscommittee.org/admin/site/documents/files/CCJEF-v.-Rell-Summary.pdf>.

- “CCJEF v. Rell Overview.” Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. <http://ccjef.org/ccjef-v-rell-overview>.

- Collier, Christopher. Connecticut’s Public Schools: A History, 1650-2000. Orange, CT: Clearwater Press, 2009. Print.

- Eaton, Susan E. The Children in Room E4: American Education on Trial. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2007. Print.

- “Reynolds v. Sims.” Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School, n.d. Web. 7 Oct 2013. <http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0377_0533_ZS.html>

- “Simon Bernstein.” The New Haven Register. 30 May 2013. New Haven Register. Web. 7 Oct 2013.

- “Sheff v. O’Neill—Today in History.” ConnecticutHistory.org. CThumanities, n.d. Web. 7 Oct 2013. <http://connecticuthistory.org/sheff-v-oneill-today-in-history/>.