The following essay gives voice to the stories of Project Concern alumni as they look back their on the experiences as participants in Project Concern, starting in the 1966. The experiences of Project Concern alumni are both unique to individual and span communally over 40 years.

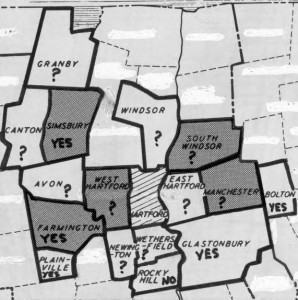

Project Concern was one of the first voluntary school desegregation programs in the United States. Project Concern was founded in 1966 by Trude Mero Johnson and Dr. Alexander Plant of the Connecticut State Department of Education. The goal of Project Concern was two-fold: (1) to promote racial diversity in suburban school settings and their surrounding communities; (2) to provide Hartford students with a highquality education that was otherwise not afforded by Hartford public schools. To participate in Project Concern students from the Hartford Community were bused to suburban communities to attend school. 1

In 1996, after the “Sheff v. O’Neil” ruling, Project Concern was reorganized. Project Concern became “Project Choice” and, later, “Open Choice” and now acts as remedy to Sheff v. O’Neil in conjunction “with a system of regional interdistrict magnet schools” 2

Project Concern Alumni: Introduction to Project Concern

The participation in Project Concern was often without choice from Project Concern alumni. Project Concern alumni were directed to participate by their families and friends. Consequently, there was ambivalence expressed amongst Project Concern alumni as they looked back on their early experiences with Project Concern. Alumni equally expressed feelings of reluctance, indifference and excitement towards Project Concern.

The parents of Project Concern alumni often made the decision for their children to participate in Project Concern. The decision was based on the premise that Project Concern would provide their children with access to a quality of education that was otherwise not afforded by the racially and economically constrained Hartford school system. As remembered by one Project Concern alumnus, “the quality of education in Hartford was not anywhere near the quality of the education in the suburbs, and that’s why parents were trying to get their children out of cities.” 3

As the parents of Project Concern alumni often made the decision for their children to participate in Project Concern, many alumni had neither a comprehensive understanding of the program nor a choice to participate in the program. For Project Concern alumni participating in the program simply meant being bused to suburban communities to attend school. The parents of Project Concern alumni expressed doing so as necessary and an opportunity to be taken advantage of despite its potential for discomfort.

Project Concern alumni responded to insisted participation in Project Concern in a manner that was dependent on their age and the place in the timeline of their schooling. Project Concern alumni who entered the program in the later years of their schooling had already established themselves among their peer groups in Hartford and often did not want to have to be apart from their peers or friends. Resultantly, these individuals viewed Project Concern unfavorably.

Lawrence Satchell’s reflection of his early experiences as a participant of Project Concern exemplify the reluctance he and other individuals felt having had entered Project Concern in the later years of their schooling. Lawrence entered the Project Concern in middle school. He attended Assumption Junior Middle School in Manchester, Connecticut and then Hall High School in West Hartford, Connecticut, graduating in 1982. Lawrence recalls that his mother pushed him (as well as his siblings) to participate in Project Concern, despite his disinterest: “[My mother] thought a little different education style would benefit her children. So, she was the one who pushed us into it. I didn’t really want to go initially, because, of course I was leaving friends, and you know like that. But she pushed me into it.” 4 Lawrence, like many other Project Concern students, did not understand the program or its social or educational benefits. In consequence, he focused on being separated from his friends and initially approached Project Concern “negatively.” 5

In contrast to Lawrence and age equivalent individuals with similar early Project Concern experiences, Project Concern alumni who entered the program early in their schooling did not have a clear opinion of participation in the program. They were too young to understand the social and educational impact Project Concern would have on their lives. Chrishaun Langs, a Project Concern alumnus who attended West Hartford public schools until her pregnancy in the eleventh grade, recalls, “I was in first grade. It really didn’t matter. I mean at the time I was just told that I was going to a different school, but it was okay.” 6 In some instances, Project Concern alumni themselves made conscious decisions to participate in Project Concern and welcomed the thought of attending a new school in a suburban community. In particular, Brenadeen Marshall, who graduated from the Mary Immaculate School in New Britain, Connecticut in 1974, signed herself up for Project Concern. Brenadeen originally planned to attend Hartford High School. However, after a change in Hartford school zoning, her neighborhood high school switched to Weaver High School. Brenadeen had long favored going to the high school that her mother attended (Hartford High School) and was resistant to going to Weaver High School. The change in options for high schools prompted Brenadeen to look for an alternative to Hartford schools. At the time, Brenadeen remembered seeing “yellow buses rolling all the time, much earlier than the average school buses.” 7 She asked her friends, who would be leaving Hartford public school after elementary school, and peers in the neighborhood about the affiliated program—Project Concern. Brendadeen knew that her parents would not support her participation in Project Concern, so she went to the program office with a friend and filled out the application on her own. 8

Ultimately, whether the decision for Project Concern alumni to attend the program was made by the families of an alumni or the alumnus him or herself, the decision was seemingly made out of the conclusiveness that participating in Project Concern was in the best interest of alumnus.

Project Concern Alumni: Extracurricular Activities, Transportation and Inclusion

Project Concern alumni who were able to experience their respective Project Concern schools and surrounding urban communities beyond the school day looked back on their experiences with positivity. Extracurricular activities led Project Concern alumni to feel included in suburban schools and communities as well as gave alumni the opportunity to build and strengthen relationships with their peers. Notably the ability to participate in extracurricular activities was linked to access to transportation. A lack of transportation forced Project Concern alumni to discontinue extracurricular activities.

Project Concern alumni often voiced that they did not mind riding the school bus despite its possible 2-hour span. During bus rides they often were able to fostered friendships with others participating in the program—especially in instances in which Project Concern participants took part in extracurricular activities.

Project Concern alumni participated in a variety of extracurricular activities as an extension of their schooling in the suburbs. Alumni, both male and female, participated in school sports (including basketball, football, volleyball, track and field and cheerleading) as well as school clubs (including dance and glee clubs) and attended school dances, movie nights and carnivals. Project Concern alumni also had the opportunity to participate in Brownies, and later Girl Scouts, as well as take drivers education courses.

When enough students stayed after for extracurricular activities, Project Concern would send an after school bus to transport participants home to Hartford. However, some Project Concern alumni remember using public transportation (public buses and cabs) to return home to Hartford after participating in extracurricular activities. In instances in which transportation wasn’t readily available Project Concern alumni stayed at the homes of friends from their respective Project Concern schools or emergency mothers. Emergency mothers were individuals in the community who would allow Project Concern alumni to stay with them overnight. They had clothes readily available for alumni for the next day and saw to it that alumni caught transportation home the next day.

Cheryl Shelton, a Project Concern alumnus who participated in the Project Concern program in Plainville, Connecticut from the start of her schooling, recalls positive experiences spent with the friends she made at schools. Specifically, Cheryl remembers instances in which Plainville schools held school dances that she and other Project Concern students wanted to attend. Cheryl stayed at the homes of friends before school dances. At her friend’s homes Cheryl “[ate] dinner, washed and changed and then [went] to the dance.” 9 After the dances, Cheryl would be picked up by her friend’s parents who would make the necessary plans for Cheryl to return to her home in Hartford. Cheryl looks back on these experiences as being “fun”: “it was fun getting into a different atmosphere and [interacting] with different people.” 10

Interestingly, despite Project Concern alumni frequenting the homes of their school friends, they rarely had school friends visit their homes. Cheryl Shelton, who grew up in Stowe Village, a Hartford project, explains that her location within the city of Hartford reflected her decision to abstain from having friends at her family home: “I would never bring anyone who with me in the projects. It was kinda rough. So I never brought anyone home.” 11 Cheryl’s sister, Marcia Shelton, who attended Project Concern participating schools in Manchester until high school, adds that the one time that the family did have her friends from the suburbs for a birthday party, the family hosted the party at her grandmother’s house because she was embarrassed by the family’s home in the Projects. 12 The reluctance of Project Concern alumni to have their friends at their homes is indicative of the social and racial barriers between the communities and subsequent lives of Project Concern alumni and their suburban counterparts.

Though Project Concern alumni had numerous positive experiences with extracurricular activities, some alumni reported that the lengthy traveling, in any capacity, from Hartford to the suburbs and back affected their ability to participate in extracurricular activities. Cheryl Shelton attested to this: Cheryl’s mother was disabled and her father absent. While her grandfather was sometimes available to drive back and forth to the Plainville schools and community, the drive was 20 miles and what Cheryl described as “tough”. 13 When Cheryl was a young girl, a cab service was made available to make the commute to and from Hartford for her extracurricular activities. However, the cab became too expensive (and the public bus too far for the commute). As a consequence, Cheryl was not able to continue with cheerleading after a year and a half of participation. Cheryl, and students who was presented with a similar situation, believed that had they been able to participate in extracurricular activities, they would have been better integrated into the suburban communities in which they attended schools. 14

Project Concern Alumni: Balancing Two Identities and Lifestyles

Throughout their participation in Project Concern alumni found themselves balancing two identities and lifestyles. As Project Concern alumni look back at their experiences, they often found that with age and, consequently, schooling their opposing identities and lifestyles became more apparent with age. That is, Project Concern alumni developed a hyper awareness of their identities as they recognized a cultural divide between the Hartford community their respective Project Concern schools and communities; experienced blatant racism; and formed relationships and friendships with their peers inside and outside the Hartford community.

Project Concern alumni expressed that participating in Project Concern was a balancing act between their identities and lifestyles in the Hartford community and in their respective Project Concern schools and communities. Antonio Champion, a Project Concern alumnus, compares the balancing between the Hartford community and Project Concern schools and communities to being bilingual: “you can speak two languages at the same time or three, and you understand the nuances between each of them and you [are] able to appreciate the nuances between them.” 15 As an individual who “spoke the languages” of both the Hartford community and Project Concern schools and communities, Antonio remembers himself developing an identity and a lifestyle that was dependent on his surroundings. Antonio was accustomed to the culture of his Hartford community. However, he knew the educational and social advantages of participating in Project Concern and felt it necessary to make adjustments in his interactions with his peers in the suburban community and with the community itself. 16 Importantly, in some instances, the changing of identities and lifestyles of Project Concern alumni between the Hartford community and their respective Project Concern schools and communities reflected both a need and a desire to fit in.

Video: Antonio Champion speaking about balancing two identities and lifestyles. 17

Project Concern alumni created a separation between their identities and lifestyles in the Hartford community and in their respective Project Concern schools and communities in reflection of an awareness of the racial and social differences between the former community and the later. Notably, the awareness of differences for Project Concern alumni developed with the progression of age and schooling.

Zyretha Langs, an alumnus who began participating in the Project Concern program during her elementary schooling, expressed that being apart of Project Concern “wasn’t a big deal” as she “didn’t have a concept of racial identity.” 18 However, as Zyretha’s schooling progressed in West Hartford public schools, she began to notice racial barriers between herself and her peers in the suburban school setting. Specifically, Zythera observed that the only minorities attending West Hartford schools were those that attended the schools as participants of Project Concern and, as students grew older, there was a prevalent divide in culture between Project Concern and West Hartford students. In consequence, Zythera felt isolated in the West Hartford school setting and was hesitant to engage in friends with her white peers. 19 The awareness of racial barriers was a product of the progression of age schooling was common amongst Project Concern Alumni and resulted in feeling of exclusion in Project Concern schools and communities. Feelings on exclusion were in contrast to those of inclusion felt from participating in extracurricular activities.

Feelings of exclusion were sometimes legitimized by blatant acts of racism in Project Concern schools and neighborhoods. These were acts mostly demonstrated as an exclusion of Project Concern alumni in extracurricular activities. Cheryl remembers a blatant act of racism during her Project Concern schooling in West Hartford: A peer of Cheryl’s in West Hartford hosted a sleep over. Cheryl wanted for her invitation to the sleep over but it never came. The individual hosting the sleepover told Cheryl she was not invited as “her parents did not like black people.” 20

Some Project Concern alumni expressed feeling as though they had two sets of friends—one set of friends in the Hartford community, the other in their respective Project Concern Schools. Other Project Concern alumni felt as though they did not have friends solely from the Hartford community, there friends were either members of their respective Project Concern schools and communities or fellow participants in Project Concern. Project Concern alumni also perceived themselves as outsiders, though generally accepted. A number of Project Concern alumni recall themselves being called “white” and “oreos” by their peers in the Hartford community and chastised for their speaking in what is noted as proper English. 21In other instances Project Concern remember themselves as being “placed on a pedestal”, as if their participation in Project Concern made them a better version of their peers in the Hartford Community. 22

Conclusively, Project Concern alumni looked back on their participation in and experience with Project Concern with both fondness and a critical lens. Project Concern afforded alumni opportunities that were otherwise not available in the Hartford community. Project Concern alumni were pushed into diversity that resulted in a hyperawareness of their identities as minority individuals living in the Hartford community as well as an advantageous vulnerability in relationships and friendship with individuals in suburban communities who were unlike themselves. When Project Concern alumni looked they backed remember were they came and how far they went for diversity and inclusion.

Works Referenced / Cited

Bernadeen Marshall, interview by Dana Banks, home of Bernadeen Marshall, March 8, 2003.

Cheryl Canino, interview by Grace Beckett, office of Cheryl Canino, November 8, 2002.

Cheryl Shelton, interview by Arthur Hardy Doubleday, telephone, November 11, 2002.

Chrishaun Langs, interview by Lauren Gutmann, office of Chrishuan Langs, February 14, 2003.

Gurren, Amanda. “Connecticut Takes the Wheel on Education Reform: Project Concern.” ConnecticutHistory.org, http://connecticuthistory.org/connecticut-takes-the-wheel-on-education-reform-project-concern/.

Lawrence Satchell, interview by Leon Gellert, Trinity College, November 18, 2002.

Marica Shelton, interview by Amanda Lydon, Trim Fashions of Wethersfield, November 15,2002.

Paul Little, interview by Dana Banks, West Hartford home of Paul Little, November 8, 2002.

Renita Satchell, interview with Jack Dougherty and students, Trinity College classroom, November 5, 2002.

Sheff Movement Coalition. “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” Video Documentaries, Paper 1, 29:20. January 1, 2008. http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp_media/1.

Trinity College. “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” Vimeo video, 29:43. 2008. https://vimeo.com/26118805.

Zyretha Langs, interview with Hilary Cramer, Capital Region Education Council (CREC),November 7, 2002.

Notes:

- Sheff Movement Coalition. “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” Video Documentaries, Paper 1, 29:20, January 1, 2008, http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp_media/1. ↩

- Sheff Movement Coalition, “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” ↩

- Renita Satchell, interview with Jack Dougherty and students, Trinity College classroom, November 5, 2002. ↩

- Paul Little, interview by Dana Banks, West Hartford home of Paul Little, November 8, 2002. ↩

- Paul Little. ↩

- Cheryl Canino, interview by Grace Beckett, office of Cheryl Canino, November 8, 2002. ↩

- Bernadeen Marshall, interview by Dana Banks, home of Bernadeen Marshall, March 8, 2003. ↩

- Bernadeen Marshall. ↩

- Cheryl Shelton, interview by Arthur Hardy Doubleday, telephone, November 11, 2002. ↩

- Cheryl Shelton. ↩

- Cheryl Shelton. ↩

- Marica Shelton, interview by Amanda Lydon, Trim Fashions of Wethersfield, November 15, 2002. ↩

- Cheryl Shelton. ↩

- Cheryl Shelton. ↩

- Sheff Movement Coalition, “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” ↩

- Sheff Movement Coalition, “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” ↩

- Trinity College. “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice,” Vimeo video, 29:43, 2008, https://vimeo.com/26118805. ↩

- Bernadeen Marshall. ↩

- Bernadeen Marshall. ↩

- Cheryl Canino. ↩

- Sheff Movement Coalition, “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” ↩

- Sheff Movement Coalition, “Forty Years of Project Concern and Project Choice.” ↩