How do magnet schools influence student enrollment? Kevin Welner (2013) introduced “The Dirty Dozen,” ways charter schools influence enrollment:

- Description and Design: What niche?

- Location, location, location

- Mad Men: The Power of Marketing and Advertising

- Hooping it Up: Conditions Placed on Applications

- As Long as You Don’t Get Caught: Illegal and Dicey Practices

- Send us Your Best: Conditions Placed on Enrollment

- The Bum Steer

- Not in Service

- The Fitness Test: Counseling Out

- Flunk or Leave: Grade Retention

- Discipline and Punish

- Going Mobile (or Not)

Do magnet schools, founded upon different goals, use the same strategies to sway their student body? This essay aims to determine which of these also apply to Hartford magnet schools, how they are used differently, and what additional approaches magnets use.

Background and Methods

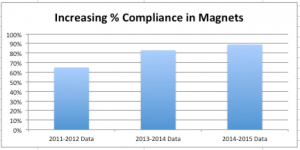

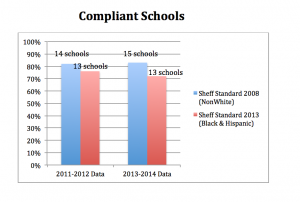

Hartford Public Schools is an “all-choice” program, in which families submit lottery applications to their preferred district school, including charter and magnet schools (Dougherty et al., 2014). Charter schools aim to improve academic achievement and educational innovation, reduce racial, ethnic, and economic isolation, and give families a choice of public education programs (Cotto & Feder, 2014). Magnet schools aim to reduce, eliminate, or prevent the racial, ethnic, or economic isolation of public school students, and offer a high-quality curriculum that supports educational improvement (Cotto & Feder, 2014) by providing special curricular themes to attract students from city and suburban districts (Dougherty, 2015). Funds for magnets can be withheld if the student body does not contain between 25% and 75% students of color, as per the Sheff vs. O’Neil standards, while no standards exist for charters (Cotto & Feder, 2014).

To look for instances of the dirty dozen, field notes collected by my classmates were analyzed. Students in the choice seminar attended magnet school open houses or the RSCO fair and recorded observations. The Regional School Choice Office (RSCO) provides information and support to Hartford families who wish to select a school best suited for their child. RSCO coordinates the application and lottery for magnets but not charters.

What Approaches Don’t Magnet Schools Use?

Location

The first approach that magnets do not use is location. Welner argues that charter schools choose their location with the students they intend to serve and the availability of transportation in mind. The Capitol Region Education Center, CREC, coordinates free transportation to magnet schools, even for students out-of-district (CREC Schools, 2015), whereas charters only guarantee transportation to in-district students (Connecticut State Department of Education, 2015).

This theme is evident in the field notes. IF, at an open house, noted that the rep discussed “how they provide transportation regardless of location.” Additionally, a magnet school student SS and JC spoke to at the RSCO fair “volunteered the information that buses are free.” AL and SG, also at the fair, described an area solely for providing information about transportation for families interested in magnets in the Hartford area. Thus, Hartford magnets are not trying to exclude students based on their location as charters may; instead, they are accommodating students from the city and surrounding suburbs. The wider transportation services offered to students attending magnet schools allow them to attract students from different backgrounds in order to uphold the Sheff standards, which charters are not held to.

Although these schools may be trying to accommodate far students, location will always play a role in enrollment. Students may opt out of a free but long commute to a magnet in favor of a quick commute to a neighborhood school. This location approach is not necessarily mal-intentioned, though, as charter schools in Hartford are locating themselves in areas of high need, likely not intentionally excluding certain students.

Advertisement

In “mad men,” Welner argues that charters shape their school’s demographics using advertising and images. Hartford magnets appear to be emphasizing diversity in their advertising to encourage students of different races to feel comfortable applying, and not simply targeting or deterring students of a certain race. AM noted that the students who represented the magnet school he visited were of different races, and the school played a video featuring “an anecdote about a white girl and a black girl who became good friends through school,” and a teacher explaining, “not one of my students look alike.”

Source: Hartford Magnet Trinity College Academy

Additionally, AG and RU observed an elementary magnet distribute brochures in English and Spanish, and EK, at the RSCO fair, noted that school representatives of magnets sometimes spoke in Spanish to families. The RSCO catalog, which provides information about Hartford’s magnet schools, is also available online in English and Spanish.

LS, at the RSCO fair, “noticed that the presenter’s spiel was different based on who came over to the booth.” He observed that when a black, seemingly lower class family came over, transportation was extensively focused on, while when a white family came, the rep skipped the transportation portion of his spiel and instead focused more on curriculum. Magnets do not appear to be targeting specific students only, but tailoring their advertisements to fit the needs of each student, again likely to adhere to the Sheff standards.

Application and Enrollment Requirements

Magnets also do not readily place conditions on applications, enrollment, or use “illegal or dicey practices,” as charters may. In Hartford, each charter requires its own application, while RSCO manages a single application for all magnets. Though long, the application only asks for basic information and rankings of open choice or magnet programs. Jumoke Academy, a charter school, requires five student essays on top of similar information, and Explorations Charter School requires two essays. Odyssey Community School, another charter, requires interested students to attend an open house. Requiring essays and attendance at events weeds out unmotivated families with likely lower-achieving kids, and lower-income working parents who cannot attend open houses and help their child write five essays. No such essays or visits, or even auditions, are required to apply to any magnet schools. Hartford magnets clearly do not make as much use of the “hooping it up” strategy as charters.

Magnets also do not use the “illegal and dicey practices” approach, in which some charters ask for Social Security cards or birth certificates, even though these cannot be required by law. Nowhere on the RSCO application was there a request for social security numbers or birth certificates, but there was also no evidence for this in any available charter applications.

Magnets also do not employ the “send us your best” strategy, in which conditions like needing a certain GPA or prerequisites are placed upon enrollment. Although few charter applications could be accessed, Explorations Charter School did employ this tactic, by requiring that students entering the high school not as freshmen already have certain number of credits. Once enrolled, students must pass 80% of their courses and be present 90% of the time. Again, although little data is available, Hartford charters appear use this approach more than magnets.

Steering Away

Magnets also do not seem to employ the “bum steer,” in which charters may steer away less desirable students. Instead of steering students away, magnets emphasize finding the right fit. IF explained that one magnet “offers a program in which a prospective and/or accepted student can shadow a current student because the school only wants students who want to be there.” EK, at the RSCO fair, observed, “several schools also encouraged parents to have their child experience a day at their school and decide for himself/herself if it would be a good fit.” Rather than the school representatives themselves steering away students who may not be the best match, they encourage students to make this “fit” judgment themselves. Thus, the magnets are getting the students who are a good fit for the school without using a manipulative approach.

What Approaches Do Magnet Schools Use?

Not in Service

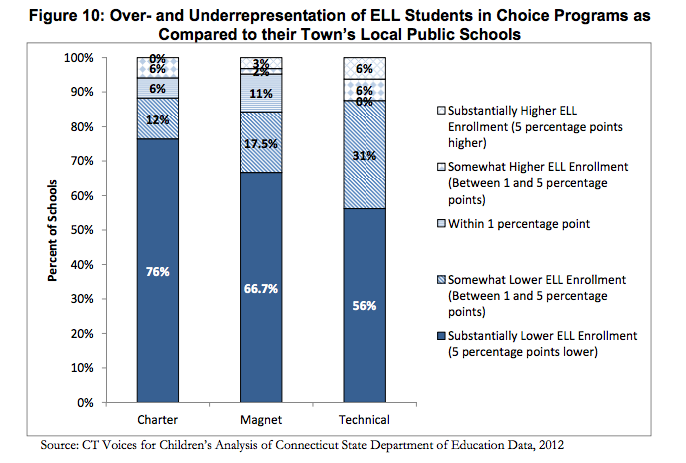

While magnets do not appear to outwardly steer high-needs students away, they do use the “not in service” approach by simply not readily providing services for a group of higher-needs students. AM, at a magnet open house, explained, “these special arts programs received a lot of airtime when things like special education and ELL programs were skimmed over.” While state law requires schools enrolling more than twenty English language learners (ELL) to offer a school-wide bilingual education program, there is no requirement that choice schools offer such a program if ELL enrollment is under this threshold (Cotto & Feder, 2014). The school’s failure to mention any services for ELL students was possibly an attempt to discourage these students from applying, saving the school from bearing the financial burden of implementing these services. ELL students in Hartford are less likely to attend choice schools than local public schools (Cotto & Feder, 2014), perhaps due to this tactic. However, magnet schools did make efforts to cater to ELL students by advertising in Spanish.

Discipline

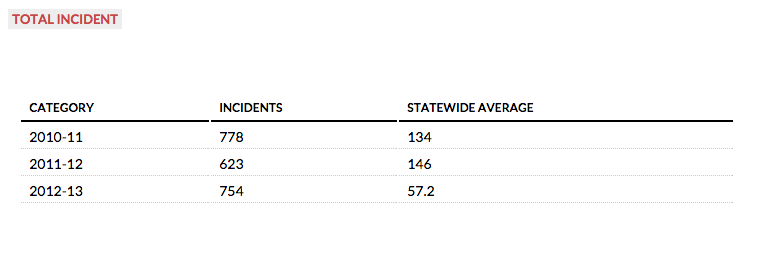

Magnets also appear to use the “discipline and punish” tactic, involving harsh discipline regimes leading to high expulsion rates. While data was unavailable for expulsion rates by school type, a CT Mirror feature compares disciplinary incidents at a given school to the statewide average. Data for the available Hartford magnet schools was perplexing; many schools reported zero disciplinary incidents in 2012-2013, however, even more reported numbers higher than the state average, most frequently school policy violations. This could either indicate great variation in school policies and disciplinary strategies between Hartford magnets, or some magnets not reporting this information. Many charters with accessible data were also above the state average, again with the majority being for policy violations. While the data does not indicate if these incidents led to expulsions, the high numbers suggest that some of Hartford’s choice schools may employ harsh discipline regimes, perhaps in an attempt to remove disruptive students, as Welner suggested.

Magnet Themes

Welner explains that charters decide early on what types of students to cater to when determining what niche the school is designed to fill, such as focusing on rigorous academics or special needs students. Magnets expand on this approach with their special curricular themes. Hartford magnet themes include arts and humanities, STEM, college prep, vocational, and character education. These themes, intended to attract students, may actually attract certain students while repelling others.

STEM schools, for instance, may attract more higher-income, well-educated families who understand the importance of such curriculum. LS, observing a STEM magnet booth at the RSCO fair, described how an Asian mother from an affluent suburb had already researched the school, and asked the representative about specific opportunities and “what the school would offer her son.” In contrast, a black mother from Hartford asked more general and “practical questions, including after school care options and transportation.” Although both expressed interest in the school, the socioeconomic difference may explain this difference in questions, and the Hartford mother’s focus on after-school care and transportation suggests that practicality, not special programs, is most important to her family. While the curricular theme may be the selling point for an affluent family, lower-income families may have to settle for a more convenient school. AL and SG, at the RSCO fair, also commented, “despite the fair being particularly minority heavy in attendance, the individuals looking at the specialized schools, whether performing arts or science based, were predominantly white.” Magnet schools serve the lowest percentage of free and reduced lunch eligible students in Hartford (Cotto & Feder, 2014). Whether or not this holds true for STEM schools, the specialized themes may partly explain why the least low-income students enroll in magnet schools.

Magnets also influence enrollment by not offering particular themes. For instance, there are no Hartford magnets with a dual language theme, which also may explain the lower ELL enrollment in Hartford magnets than local public schools (Cotto & Feder, 2014). Perhaps magnets would attract a wider population if they expanded the breadth of their themes.

Availability of Information

Another bias in choice schools Welner did not account for is the availability of information about the schools. Information can often be found online, however, not every family in Hartford owns a computer, or knows how to use one, creating a bias against low-income or illiterate parents, also likely biasing against lower achieving children. Valuable information is also gathered from attending open houses and school fairs that some parents cannot easily attend. HH, at the RSCO fair, noted “some parents expressed concern that they may not be able to make it to the specific info sessions offered by some schools due to the fact that those sessions are normally offered during weekdays.” Working, lower-income parents likely have less flexible hours, or are unable to afford childcare, and cannot attend open houses to get the important information. Although this likely impacts student enrollment, this is probably unintentional, and thus more “accidental” than “dirty” in biasing access to choice schools.

Approaches with Limited Data

Welner discusses additional approaches, however limited data for these is available. Such strategies include “flunk or leave”, in which school officials threaten to hold the student back a grade if they remain in the school, “the fitness test,” in which parents of less successful students are counseled to consider alternative options, and “going mobile (or not),” in which charters decide whether or not to backfill the students they lose, either during the year or for higher grades. Future research is needed to determine if these apply to Hartford magnets.

Conclusion

Many of these approaches mentioned in “The Dirty Dozen” that charter schools may use seem to be less readily employed by Hartford magnet schools. Magnets do not appear to use Welner’s tactics of location, advertising, conditions placed on application and enrollment, dicey practices, or the bum steer in the same way as charters. However, magnets do seem to use Welner’s not in service, discipline and punish, and niche approaches, and their own approaches of theme and information available. Magnets seem to be well intentioned and trying to create a diverse student body catering to different types of families and students rather than purposely trying to exclude certain students. However, the attempts do not always accomplish this inclusiveness, and some factors may unintentionally leave some students behind. While magnets may advertise in Spanish, for instance, they still enroll a smaller ELL population than the neighborhood schools. This indicates that magnets do not intend to exclude this population, but other factors play a role. If choice schools wish to prevent these “accidental” factors that make certain students less likely to enroll from occurring, these populations must be identified so that choice schools can better recruit these students.

References

Attend and Apply (2015). Explorations Charter School. Retrieved from http://explorationscs.com/attendapply.html

Charter School Questions and Answers. (2015).Connecticut State Department of Education. Retrieved from http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/lib/sde/pdf/equity/charter/faqs.pdf

Cotto, R. & Feder, K. (2014). Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs. CT Voices for Children. Retrieved from http://www.ctvoices.org/sites/default/files/edu14choicewatchfull.pdf

Dougherty, J., Zannoni, D., Block, M., & Spirou, S. (2014). Who Chooses in Hartford? Report 1: Statistical analysis of Regional School Choice Office applicants and non-applicants among Hartford resident HPS students in grades 3-7, Spring 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository. Retrieved from http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1045&context=cssp_papers

Dougherty, J. (2015). A Vocabulary for Understanding School Choice in Connecticut. Presentation for CSPL 341: Innovation in Education- Choice Seminar.

How to Apply (2015). Odyssey Community School. Retrieved from http://www.odysseyschool.org/about-odyssey/admission-information

Explorations Charter School Application (2015). Retrieved from http://explorationscs.com/images/2015-2016_Application_Long_Form_.pdf

IF, SS, JC, AL, SG, AM, EK, LS, HH, AG, RU (2015). Class Field Notes.

Jumoke Academy Application (2015). Retrieved from http://jumokeacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/JumokeAcademyApplication2015-2016.pdf

RSCO Catalog (English). (2015). The Regional School Office. Retrieved from http://www.choiceeducation.org/javascript/tiny_mce/plugins/filemanager/files/RSCOcatalogFINALNov19.pdf

RSCO Catalog (Spanish). (2015). The Regional School Office. Retrieved from http://www.choiceeducation.org/javascript/tiny_mce/plugins/filemanager/files/RSCOcatalogSPANISH_web.pdf

RSCO Lottery Application (2015). The Regional School Choice Office. Retrieved from http://www.choiceeducation.org/javascript/tiny_mce/plugins/filemanager/files/RSCOlotteryapp201516_FINALDRAFT.pdf

The RSCO Transportation Zone. (2015). The Regional School Choice Office. Retrieved from http://www.choiceeducation.org/javascript/tiny_mce/plugins/filemanager/files/rsco_transportationzone.pdf

Transportation. (2015). CREC Schools. Retrieved from http://www.crecschools.org/for-parents/transportation/

Video. (2015). Hartford Magnet Trinity College Academy. Retrieved from http://hmtca.hartfordschools.org/

Welner, K. G. (2013). The Dirty Dozen: How Charter Schools Influence Student Enrollment. Teachers College Record. [online], http://www.tcrecord.org

Your School (2015). The CT Mirror. Retrieved from http://projects.ctmirror.org/yourschool/index.php