Setting the stage—an overview of The Hartford Public Schools (HPS) reform:

Urban education is in a state of crisis and reform efforts must be reevaluated in order to properly address and confront the systemic issues that plague urban school districts. The educational reform movement in Hartford, Connecticut has seen differences in leadership over the last 13 years. With three different superintendents, room for variance in approach is wide. Anthony Amato’s strategy to pull Hartford Public Schools out of the mud involved a strict and regimented curriculum overhaul that is starkly different from those of Steven Adamowski and current Superintendent Christina Kishimoto. Recently, Hartford has adopted a portfolio-based school reform. What is portfolio reform and is it working to lift urban education in Hartford? A crux of this reform model is the notion that we must not strive to create a great school system but we must instead move forward to create a system of excellent schools. Portfolio-based reform is a viable strategy for Hartford given its disheartening record of student test results sinking far below state and national averages. Both local and national advocates alike proclaim that HPS is the poster child for portfolio reform because of the visible and dramatic shifts in student performance, as marked by continued positive trends in student achievement.

What is portfolio-based reform anyway?

Portfolio-based school reform is a model that guarantees continuous improvement in academic achievement by flipping failing district schools, leaving nothing behind but the physical bedrock foundation of the school itself. Founded and backed by the Center for Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) at the University of Washington, Hartford has recently adopted this improvement tactic and has received instant returns, classifying itself as the poster child for portfolio reform in only a few short years. Through seven key components, portfolio reform redesigns or rebuilds schools, giving total control and autonomy to each school shortly thereafter. To successfully activate CRPE’s strategy, the following seven measures must be adhered to.

1. High-level options and choices for all families

2. School autonomy

3. Student-based funding

4. Talent Management approach

5. Theme-based partnerships

6. Performance-based accountability for schools

7. Extensive public engagement

These components allow for the creation of diverse school options within Hartford’s district. In essence, the portfolio strategy is multifaceted and includes a balanced composition of several mini methods of reform. This unique combination of strategies allows for the greatest lasting impact in educational improvement. Additionally, these facets suggest that long lasting education reform is multidimensional and continual as it evolves with the demands of the times. Static reform efforts were unable to tackle the systemic educational equity barriers prevalent among Hartford schoolchildren. These seven facets, however, serve to address the challenges and shortcomings of HPS by extending support in multiple directions. Of the seven fundamental components, listed above, only three have proven central ingredients to Hartford’s installment of portfolio reform: school choice, autonomy, and accountability.

School Choice: What is it?

School choice emerged as a result of Sheff v. O’Neill, a landmark Supreme Court case calling for regional school desegregation in the greater Hartford area, and the Hartford Public Schools’ All-Choice Initiative (Caron 12). Put simply, the choice system affords parents the opportunity to actively select which school they wish their child to attend. Much like anything else in this world, with choice comes competition. Indeed, rivalry between schools is a hallmark feature unique to the operation of this method of reform. Each school faces the intrinsic challenge of offering students a premiere education, one whose record is marked by high levels of student achievement and parent satisfaction. Perhaps it is the case that excellence is the product of fear, as schools are habitually confronted with the looming threat of losing students to higher performing schools in consequence of choice implementation (Hoxby 4). Whatever the case, the district choice design instigates school turnaround by successfully increasing the number of excellent schools.

What are its limitations?

Though an innovative remedy to Hartford’s broken school system, school choice does in fact claim a few shortcomings. In its earliest stages, nothing was in place to support parents as they navigate the complex school selection process. They were left to base their child’s placement decision on a word-of-mouth basis, inquiring within their social networks as to which local schools had the best reputations (Teske 12). Of course, answers were subjective and varied by social association. To assist parents in making informed decisions, an interactive website was created in 2008 by Jack Dougherty, a Trinity College Educational Studies Professor. SmartChoices allows parents access to a wealth of perspective school information simply by providing their home address, such as a particular school’s test goal, test gain, racial balance, and distance from home. Though not always the case, some parents used SmartChoices as a tool to select schools on the basis of race, to ensure their child was part of the majority, and location, to make travel arrangements simple (Dougherty et. Al 7). Achieve Hartford, a local education reform agency, was also quick to identify this issue and as a result, launched a choice education program for parents. Today, Achieve Hartford continues to support parents by offering one-on-one counseling and regularly facilitating workshops to ensure parents are making informed decisions and can complete applications with ease (Achieve Hartford: Parent Engagement 1).

Autonomy: What is it?

School autonomy remains at the center for portfolio reform in Hartford. Autonomy allows schools to make decisions that will best benefit their students such as who to hire, how to spend their budget and what the curriculum should look like. Because each individual school knows their particular students well, they are the body best equipped to make decisions about the allocation of resources. In order to influence student achievement, autonomy not only means freedom from a central governing body, but supplying schools with the necessary tools to do so (VCE Study Guides 1). Essentially, autonomy localizes control by empowering individual institutions to call the shots.

What are its limitations?

School autonomy empowers academic institutions to make decisions that they deem best. This instills a lot of responsibility within schools to know their student body and decide appropriate courses of actions and methods of daily operations. Not only does it instill a lot of power in a particular school, it instills a lot of power in school leaders and fully trusts their ability to make sound decisions for their schools. Autonomy implies that schools and their leaders do not have to answer to a higher authoritative power and does not include measures for the possible abuse of power and authority. Ultimately, school autonomy weakens the power of higher governing bodies and places an overwhelming onus on schools and their leaders. Essentially, there are no safeguards in place to reprimand or account for internal corruption on even the most minute scale.

Accountability: What is it?

Accountability finds promise in overall school performance and individual student achievement. It is mainly driven by test results and seeks avenues for continuous improvement depending on the nature of students’ scores. It seeks to replicate successful schools, support struggling schools and close chronically low-performing schools (CRPE: Performance-Based Accountability for Schools). Under a portfolio model, certain measures influence which schools are replicated, which are supported and which are closed. Some of these measures are standardized test scores, school climate, graduation rates and organizational health. Most notably, the portfolio model aims to drive accountability from multiple players: policy-makers, elected officials, school administrators, educators, parents, and even students. Each role is different, but each result is the same: positive outcomes stemming from responsible actions.

What are its limitations?

Accountability in schools takes multiple forms such as performance-based accountability and student-accountability. One shortcoming of this particular facet is that performance-based accountability does not absolutely account for schools that continue to miss the mark. Although schools may report reasonable test scores, it does not necessarily signify students’ college readiness, access to a successful career path, or even active role in civic engagement (Teske et al. 7). It is worth noting, however, that student accountability is enhanced by parental involvement and ability to choose the schools they attend. Local school governing agents or bodies must monitor school performance and apply accountability based on outcomes like test scores (Teske et al. 7).

Hartford’s past reform efforts and leaders:

In order to place portfolio-based reform within its current context, it is important to understand the missions, ideologies, and goals of the three most recent superintendents in Hartford.

Anthony Amato: Codified curricula

The Hartford Public School district has undergone dramatic systemic changes in the past 13 years. While the end goals of increasing student achievement indefinitely still remain, the methods that teachers have adopted and superintendants have implemented are vastly different. In 1999, Anthony Amato bravely assumed position as the superintendent of the Hartford district. Amato was inheriting quite the job; in 1998, just 13 percent of Hartford’s fourth graders reached state goal on the Connecticut Mastery Test (Archer 1). In 1999, the district improved more in both math and reading scores than it did in the previous four years combined (Archer 1). Something was obviously working, but ultimately, Amato could not implement the proper reforms to invigorate and drastically change HPS.

Not everyone was a fan of Amato’s application of codified curricula, as many teachers felt that their creativity was being jeopardized. Supplementary enrichment programs, such as Soar to Success and Early Success, pulled students with reading difficulties out of the classroom and placed them into small group discussions with their struggling peers (Archer 2). Of the numerous strategies in place, Amato’s main goal was to institute uniformity across the district. Therefore, if someone were to peer into any first grade classroom in the city at 10am, students would be reading the same story or tackling the same math problem (Archer 2). The codified method present in elementary school was also applied to middle schools; this approach was apparent in the tracking materials that teachers used to assess and monitor their students (Archer 3).

Why did regimented and strict practices make sense in Hartford? According to the 2000 Census data, 46.5 percent of children over five years old spoke a language other than English at home (United States Census Bureau 1). Undeniably, Hartford is a melting pot of different cultures and languages. Nearly one-fifth of Hartford residents were born outside of the United States and, of this subset, 66 percent were Latin American decedents (United States Census Bureau 1).

What did this mean for schools? During Amato’s reign, many students in the district were, and continue to be today, children of immigrants. For families that moved around frequently, this standardization in approach ensured that if students were to relocate within the district, and therefore attended a different district school, they would maintain on track with their new set of peers (Archer 3).

Hartford’s diverse global demographics are reflected in its district’s student body. The classroom approach must reflect the needs of the student body and that is exactly what Amato’s approach did. While it was a step in the right direction, the standardization of the curriculum did not yield the improvement in student achievement that Amato promised. Consequently, Amato left HPS after a rocky three and a half years of service. In 2006, Steven Adamowski took over the district’s school system after a three-year stint by Robert Henry, his predecessor (Gottlieb 1). He had the intention of instituting a major makeover: he aimed to shift the focus away from curricular uniformity by implementing a balanced approach to Hartford’s reform plans.

Steven Adamowski: Balanced approach

In a presentation given at Trinity College in November of 2009, Dr. Steven Adamowski stated his vision for HPS by highlighting the difference in reform approaches between him and former superintendent Amato. In his public address, Adamowski declared, “We will take HPS from a bureaucratic, dysfunctional, low performing school system to a system of high-performing, distinctive schools of choice. The attainment of Hartford students in reading, math, science and college readiness will be reflective of the high educational outcomes of the State of Connecticut” (The Politics of Educational Reform in Hartford Public Schools 2). His vision for Hartford reform was contingent upon two principles: an all-choice system of schools and managed performance/empowerment theory of action (The Politics of Educational Reform in Hartford Public Schools 5). The all-choice system is strikingly similar to what we have come to know today as a definitive characteristic of HPS’ portfolio system. In this regard, parents were empowered to make choices from a broad array of strong inter and intra district schools. Their preferences were made simple and transparent to ensure immediate change. Adamowski’s empowerment theory of action also hinted at ideas prominent in Hartford’s current state of portfolio reform since the district defined its relationship with each school based on its performance under his reign. Additionally, autonomy increased for higher performing schools, which forced chronically low-performing schools to either redesign or close (The Politics of Educational Reform in Hartford Public Schools 4). Ultimately, Adamowski worked with a sense of urgency that was that methodical, reasonable and effective but even still, it was not enough to completely revive Hartford schools.

Christina Kishimoto: Portfolio-based reform

Christina Kishimoto came to power on July 1, 2011, as superintendent of HPS. She immediately adopted a system of portfolio-based reform, casting Hartford’s mended education system in the national limelight. Essentially, the main difference between Amato’s methods and Kishimoto’s strategies is the switch from curricular uniformity to curricular autonomy. Recently, Kishimoto has launched a portfolio model of reform that grants total autonomy to all schools and gives each individual institution the opportunity to run its school as it sees accordingly for its particular student body.

Christina Kishimoto came to power on July 1, 2011, as superintendent of HPS. She immediately adopted a system of portfolio-based reform, casting Hartford’s mended education system in the national limelight. Essentially, the main difference between Amato’s methods and Kishimoto’s strategies is the switch from curricular uniformity to curricular autonomy. Recently, Kishimoto has launched a portfolio model of reform that grants total autonomy to all schools and gives each individual institution the opportunity to run its school as it sees accordingly for its particular student body.

Why this transition?

HPS has hired different superintendents in the past with different curricular strategies in order to uplift urban education in Hartford. Therefore, it is only natural and within reason that there have been shifts in ideology from Amato to Adamowski to Kishimoto. Amato cited a curricular uniformity approach that attempted to increase student achievement by regimenting the curriculum across the entire city. There was little room for teacher and curricular creativity. Adamowski began to broaden the curriculum yet still maintained loyal to a finite list of reforms and regulations. His balanced approach attempted to implement change in HPS without the shock and upheaval that Amato adopted. Kishimoto currently utilizes a portfolio-based reform model that has inverted elements of Amato’s strategies which empowers all schools with the choice to run their schools how they best see fit. Under Kishimoto, Hartford’s goal is not to create a great school system but rather form a system of excellent schools.

HPS has hired different superintendents in the past with different curricular strategies in order to uplift urban education in Hartford. Therefore, it is only natural and within reason that there have been shifts in ideology from Amato to Adamowski to Kishimoto. Amato cited a curricular uniformity approach that attempted to increase student achievement by regimenting the curriculum across the entire city. There was little room for teacher and curricular creativity. Adamowski began to broaden the curriculum yet still maintained loyal to a finite list of reforms and regulations. His balanced approach attempted to implement change in HPS without the shock and upheaval that Amato adopted. Kishimoto currently utilizes a portfolio-based reform model that has inverted elements of Amato’s strategies which empowers all schools with the choice to run their schools how they best see fit. Under Kishimoto, Hartford’s goal is not to create a great school system but rather form a system of excellent schools.

What evidence supports that Hartford’s portfolio reform is in fact working?

Portfolio-based reform is a viable option for HPS because it enhances and replicates what is working and does away with what is not. In order to fully understand progress, it is helpful to break portfolio-based reform into three specific school models: redesign, magnets and new schools (see details in blue bubble below).

In analyzing data from the Achieve Hartford’s What Do the Results Tell Us Report, it becomes clear that portfolio-based reform is in fact working to provide students a quality education, as measured by improved test scores, and ultimately to close the withstanding achievement gap. Look at the graph below: redesigns, magnets, and new schools at the elementary and middle school level have demonstrated compelling progression across the board.

When comparing these gains to advances made by elementary and middle schools exempt from reform influences, as their prior performance records were sufficient enough to continue operations as usual, non-redesigns have crawled to a plateau or have made statistically insignificant gains in comparison to schools influenced by portfolio reform. This standstill is demonstrated most accurately by the individual non-redesign graph below.

When schools are being reworked and restructured, they are showing gains in student achievement. While there are certainly success stories amongst non-redesign schools, it is clear that schools that have undergone reform are improving at a faster rate.

Ultimately, the elaborate process of creating a system of great schools will only be complete when either: high achieving academic institutions supersede Hartford’s substandard schools, when Hartford’s substandard schools blow up their defective model and institute an entirely new academic arrangement conducive to superior student achievement, or when Hartford’s substandard schools are subject to closure.

Bibliography

“A Digital Guide to Public School Choice in the Greater Hartford Region.” SmartChoices. Trinity College, Achieve Hartford. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://smartchoices.trincoll.edu>.

Achieve Hartford! Hartford Public Schools: 2012 CMT and CAPT Scores: What Do the Results Tell Us? [Hartford, CT] 16 Aug. 2012, Annual Report ed

Adamowski, Steven. “The Politics of Educational Reform in Hartford Public Schools.” Hartford Public Schools, Nov. 2009. 30 Nov. 2012. <https://www.dropbox.com/s/l9tfum3281srn5k/Adamowski%20HPS%20Nov2009.ppt>.

Archer, Paul. “Under Amato, Hartford Schools Show Progress.” Education Week. Educational Week, 1 Mar. 2000. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2000/03/01/25hartford.h19.html>.

Caron, Joel et Al. “What Factors Are Most Influential In A Hartford Parent’s Decision To Choose A High Test Scoring School For Their Child?” Trinity College: Smart Choice Econometrix (2009) Achieve Hartford. 30 Nov. 2012.

“Choice Education Program.” Programs. Achieve Hartford. Web. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://achievehartford.org/prog_pt.php>.

Gottlieb, Rachel. “City Schools: A Balancing Act.” Hartford Courant. 30 Oct. 2003. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://articles.courant.com/2003-10-30/news/0310300044_1_schools-anthony-amato-robert-henry-city-s-most-troubled-schools>.

“Hartford (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau.” Hartford (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau, 2000. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/09/0937000.html>.

Hill, Paul. “Performance Management in Portfolio Districts.” CRPE (2009): Achieve Hartford. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/pub_dscr_portfperf_aug09_0.pdf>.

Hoxby, Caroline M. “School Choice and School Productivity (or could school choice be a tide that lifts all boats?).” National Bureau of Economic Research (2002): Achieve Hartford.

Jack Dougherty, Diane Zannoni, Maham Chowhan ’10, Courteney Coyne ’10, Benjamin Dawson ’11, Tehani Guruge ’11, and Begaeta Nukic ’11. “School Information, Parental Decisions, and the Digital Divide: The SmartChoices Project in Hartford, Connecticut.”

“Model Portfolio District.” Hartford Public Schools. CRPE. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://www.hartfordschools.org/index.php/about-us/model-portfolio-district>.

“School Autonomy – VCE Study Guides.” VCE Study Guides RSS. VCE English and ESL, 2011. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://www.vcestudyguides.com/guides/language-analysis/australian-issues-in-the-media/school-autonomy>.

Smarick, Andy. “The Disappointing but Completely Predictable Results from SIG.” Flypaper Commentary. Thomas B. Fordham Institute: Advancing Education Excellence, 19 Nov. 2012. 30 Nov. 2012. <http://www.edexcellence.net/commentary/education-gadfly-daily/flypaper/2012/the-disappointing-but-completely-predictable-results-from-SIG.html>.

Teske, Paul, Jody Fitzpatrick, and Gabriel Kaplan. “Opening Doors: How Low-Income Parents Search for the Right School.” University of Washington: Daniel J. Evans School of Public Affairs (2007)

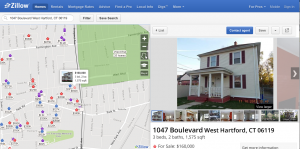

This is because the location allowed for three schools in very close proximity. My children would be able to attend Bristow Middle School, Environmental Sciences Magnet, and the Smith School of Science all which were close enough for myself to get to incase of an emergency. The house was on the pricier end of the spectrum with a total cost of $160,000 and a thirty percent year fixed price of $656. However, it was the most centrally located in terms of schooling which I felt was an asset that was invaluable. It also was one of the few houses with three bedrooms and two baths.

This is because the location allowed for three schools in very close proximity. My children would be able to attend Bristow Middle School, Environmental Sciences Magnet, and the Smith School of Science all which were close enough for myself to get to incase of an emergency. The house was on the pricier end of the spectrum with a total cost of $160,000 and a thirty percent year fixed price of $656. However, it was the most centrally located in terms of schooling which I felt was an asset that was invaluable. It also was one of the few houses with three bedrooms and two baths.