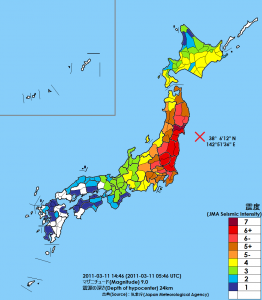

On March 11th, 2011, Japan was struck by one of the hardest earthquakes in recorded history. This 9.0 magnitude  event, centered just off the coast of the Oshika Peninsula, could be felt all over Japan. Sadly, the earthquake triggered a tsunami which caused massive damage to the coastline of the Tohoku region of northeastern Japan. The combined catastrophes resulted in over 15,000 deaths, 6,000 injuries and more than 2,500 people still missing. Damage to the afflicted areas was immense, with some smaller villages being completely destroyed. Larger cities such as Sendai and Ishinomaki saw miles of open coastline essentially erased, while smaller towns such as Minamisanriku and Rikuzentakata were almost entirely destroyed.

event, centered just off the coast of the Oshika Peninsula, could be felt all over Japan. Sadly, the earthquake triggered a tsunami which caused massive damage to the coastline of the Tohoku region of northeastern Japan. The combined catastrophes resulted in over 15,000 deaths, 6,000 injuries and more than 2,500 people still missing. Damage to the afflicted areas was immense, with some smaller villages being completely destroyed. Larger cities such as Sendai and Ishinomaki saw miles of open coastline essentially erased, while smaller towns such as Minamisanriku and Rikuzentakata were almost entirely destroyed.

Even today, three years later, thousands of people in the afflicted areas still reside in temporary housing, as reconstruction efforts move forward in an attempt to rebuild. Yet, there are many who have moved away from the area, the pain too strong to remain. Others work towards rebuilding in safer locations, in the hopes that should an event like this ever happen again, they will not find themselves among the victims.

In the three years that have passed, the combined efforts of volunteers, civil services and private firms have made vast strides towards returning to ‘normal’. The arduous task of simply clearing away the nearly unfathomable amount of  debris and sludge left behind is nearly finished in most areas. Even buildings not completely destroyed by the tsunami have been ruined by the leftover sludge drudged up by the waves, they too had to be destroyed. This affects an area far greater than that of either the Kanto or Kobe earthquakes, spanning nearly the entire coastline of Tohoku. Although most of the initial clearing has been completed, still hundreds of millions of tons of debris sits, waiting to be processed at specialized ‘recycling’ centers where it can be processed, cleaned and reused for things such as landfills. This is a process that will take many years, with these centers limited on how much they can process in a day and smaller villages having limited access to logistical support.

debris and sludge left behind is nearly finished in most areas. Even buildings not completely destroyed by the tsunami have been ruined by the leftover sludge drudged up by the waves, they too had to be destroyed. This affects an area far greater than that of either the Kanto or Kobe earthquakes, spanning nearly the entire coastline of Tohoku. Although most of the initial clearing has been completed, still hundreds of millions of tons of debris sits, waiting to be processed at specialized ‘recycling’ centers where it can be processed, cleaned and reused for things such as landfills. This is a process that will take many years, with these centers limited on how much they can process in a day and smaller villages having limited access to logistical support.

In addition, volunteers are still needed for rebuilding not only the buildings that were destroyed, but also the fishing and

farming industries. Because the tsunami not only destroyed facilities and equipment related to these jobs, but also killed or drove away workers, there are limited personnel available to work. Add in the loss of sea life in the area from the tsunami washing them away, as well as low-lying farmland due to inundation with salt water, and you find these industries will take years to recover.

Still, things are getting better. Many cities are in the process of rebuilding, in Rikuzentakata they have constructed a 600 meter conveyor belt (Expected to reach 3km by July) to help transfer soil from a nearby hill to the town center which they plan to elevate by 11 meters. Ishinomaki, where the town center has been reduced to a barren plain, has begun it’s plans to construct 4,000 new homes by March 2016. (McCurry, 2014) Some people see this progress and forget that there is more to volunteerism than just manual labor.

All over Tohoku, residents feel the ebb of volunteerism fading as time moves on. Although physically the area has been stabilized, emotionally the need for aid is just as important as ever. There are numerous volunteer groups across Tohoku who’s goal is not to build anything, but to interact with communities, to show them that people still care. If you were to ask the people in Tohoku, as Michael Sera (2014) did, you’d doubtless get a response similar to this, “When we spoke to him, he indicated that the number of volunteers to the area had greatly decreased. Suzuki now wants more visitors to come and just spend time enjoying the region, as it is important for the people of Minamisanriku to have interaction with others.” Michael got a similar response from another resident, “Rather than trying to force volunteers to do laborious tasks, he just wants them to come see the area firsthand.” This shift in the style of volunteering shows a long-term vision of volunteering, where people no longer come for a week or a month to perform labor, but to anyone who can give even a moment to acknowledge that these people are not forgotten.