Retired professors still pursue their passions

By Mary Howard

– Leslie Desmangles

PROFESSOR OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, EMERITUS

“I haven’t been bored a single moment,” says Leslie Desmangles, professor of religious studies and international studies, emeritus. Though retired since 2018, he continues his research and writing. And he is not alone. The Trinity Reporter recently checked in with Desmangles and five other retired faculty members who are busier than ever and engaging their passion for learning every day.

Desmangles, who specializes in the anthropology of religion, recently finished writing two long chapters—one on Rastafari and another on Judaism—for a book on the religions of the Caribbean that will be released by Oxford University Press later this year.

He also is enjoying a newfound interest in Christopher Columbus. “I am fascinated by what led him to travel to the other side of the world,” says Desmangles, who is studying the explorer’s journals and those of others who accompanied him.

Desmangles says he found a sense of community among Trinity faculty members, in his own and in other departments. “I had frequent scholarly discussions with my colleagues, which enriched my ongoing research and publication,” he says.

When not writing or researching, Desmangles teaches a course in Caribbean studies at the University of Hartford.

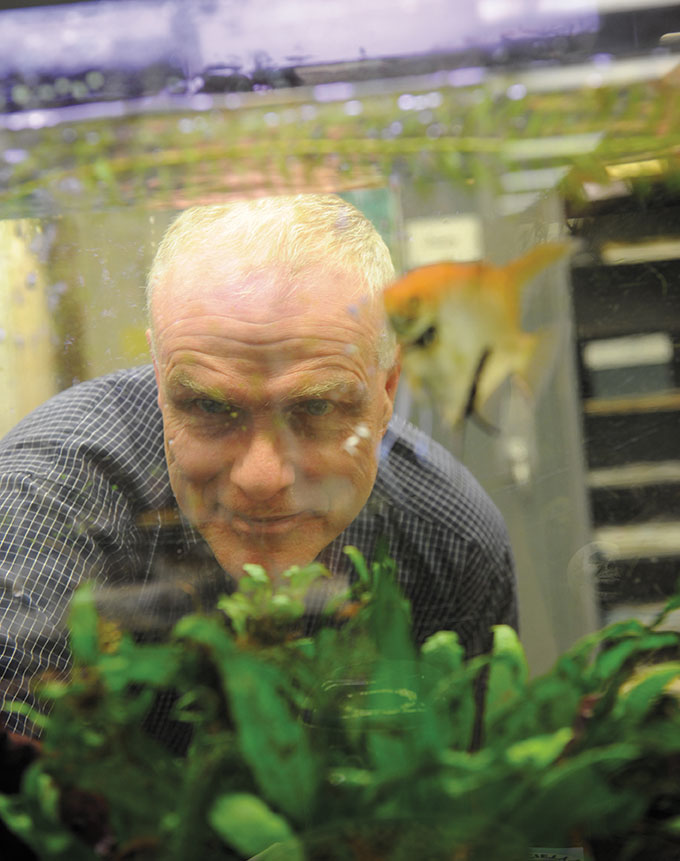

– Craig Schneider

CHARLES A. DANA PROFESSOR OF BIOLOGY, EMERITUS

Craig Schneider, Charles A. Dana Professor of Biology, Emeritus, says he’s “publishing like crazy.” As a specialist in the phylogenetics of marine algae, Schneider continues to identify new species, placing them on the tree of life, a branching diagram that illustrates the evolutionary relationships among various biological species based on their gene sequences. He estimates that he has identified between 70 to 80 new species of algae during his career.

“I love my work. I love looking for new species. I remain curious about all that we don’t know,” he says. Since retiring from Trinity in 2020, he spends every weekday and many Saturday mornings in his at-home lab. “If my wife asks me to do something on a Saturday, I usually acquiesce,” he says.

While these professors were at Trinity, they were conducting their research while teaching a full course load, says Takunari Miyazaki, associate dean for faculty development and associate professor of computer science. “Now they can devote all their time to their passion for scholarship and research,” he says.

Milla Riggio, James J. Goodwin Professor of English, Emerita, echoes this. “The only thing we retire from is teaching,” she says. When she left Trinity in 2018, she made commitments to write seven essays for various publications, including scholarly articles on the film versions of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew and several articles on the Trinidad and Tobago Carnival. She also is working on two books, a study of the Abraham legend and Compensatory Masquerade: The Healing Spirit of Trinidad Carnival, co-written with German scholar Patricia Alleyne-Dettmers.

– Milla Riggio

JAMES J. GOODWIN PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, EMERITA

“If we have active research interests, we have more time to pursue those in retirement,” says Riggio, who became interested in the historical and cultural significance of the Trinidad and Tobago Carnival in the ’90s. “Shakespeare and my carnival are kindred spirits,” she says.

Miyazaki notes, “These distinguished scholars chose a career in academia because they have a passion for learning,” adding that the support they received from Trinity over the years fostered this passion. “It is a natural progression for them to continue their research after retirement,” he says.

Schneider says that Trinity gave him the resources to carry on a very active program of research while teaching. These resources included institutional leaves and funding for fieldwork during his first decades at the college. “Yes, it all took a drive from within, and that’s always been present,” he says, “but the college truly nurtured my success over the years.” Schneider adds that, due to his track record of publications written while he was at Trinity, he secured funding from the National Science Foundation that fostered his research later in his career and into retirement.

The support received by these professors was not only in the form of funding, says Riggio. They also were given the freedom to follow their own research interests. “Where else would I be allowed to turn like a whirling dervish in so many different directions? I wasn’t forced to be the Shakespearean. I was allowed to find my own passions,” she says.

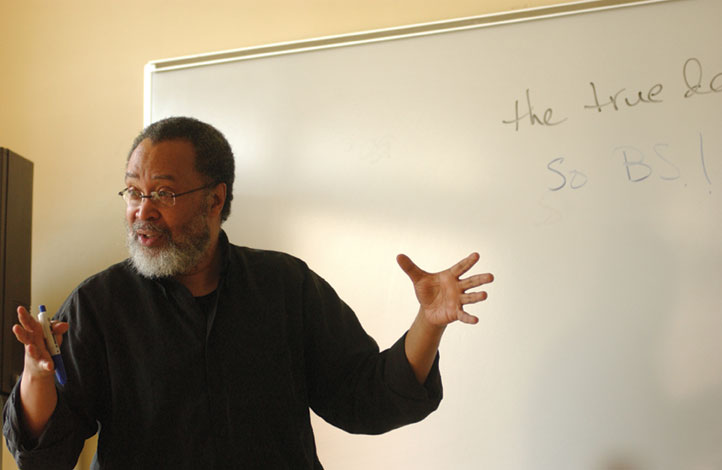

– Maurice Wade

PROFESSOR OF PHILOSOPHY, EMERITUS

During his career, Maurice Wade, professor of philosophy, emeritus, has studied and taught environmental philosophy, philosophy of the body, African philosophy, ethics and public policy, race theory, and Latin American and Caribbean philosophy. “When I became interested in something, I developed a new course,” he says.

Retired since July 2021, Wade is devoting much of his time to reviewing the unpublished personal notebooks of the Trinidadian intellectual and activist Lloyd Algernon Best. He plans to publish on the philosophical foundations of Best’s thoughts. “I believe he is a figure whose thinking should be better known,” he says.

Wade also is developing a model course on colonialism and anti-colonialism in the Caribbean. This digital course will use story-mapping tools to provide a historical narrative of text, images, and maps of the Caribbean.

– Joan Morrison

PROFESSOR OF BIOLOGY, EMERITA

Joan Morrison, professor of biology, emerita, retired in 2017. “At Trinity, we could study what we wanted to study,” she says. A conservation biologist, she helped launch the college’s Environmental Science Program in 2002 and served as its director from 2004 to 2008. She also conducted a well-publicized study of red-tailed hawks living in downtown Hartford.

But her main passion for the last 30 years has been monitoring a population of crested caracaras at the Archbold Biological Station in Florida. She says these threatened raptors are losing their habitat to rapid development in the area. Morrison notes that she is the only biologist studying these birds, which she has done since she was a University of Florida graduate student. And she has no intention of stopping. “When you spend this much of your life studying and being humbled by an animal, you want to know what’s happening to it,” she says.

For Judy Dworin ’70, professor of theater and dance, emerita, “Trinity was a fertile and active environment that inspired me to go beyond myself.” During her 43 years at Trinity, Dworin established the college’s dance program, co-founded the Trinity/La MaMa Performing Arts Program in New York City, and was instrumental in creating the Department of Theater and Dance, which she chaired for many years.

“That drive I experienced at Trinity led me to create something on my own,” says Dworin. In 1989, she founded the Judy Dworin Performance Project (JDPP), now called the Justice Dance Performance Project, which examines social issues through dance-theater performance and engagement with the arts. She also established a performance residency for women incarcerated at the York Correctional Institution, Connecticut’s only state prison for women.

– Judy Dworin

PROFESSOR OF THEATER AND DANCE, EMERITA

“Retirement never felt real to me,” says Dworin. “I have never worked harder in my life.” She continues to lead the JDPP, and—despite COVID-19 restrictions—her company has been performing regularly, including a commissioned piece staged at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford. Though retired from the college since 2015, she teaches a field study in a course offered through Trinity’s Human Rights Program that examines the intersections of the arts, prison, and human rights by involving students in a performance project with returned citizens.

For Dworin and the others, their involvements extend beyond academics. Wade runs a reading group on works by and about writer James Baldwin that includes retired and current members of the Trinity faculty. Morrison gives bird-banding demonstrations to students in her community near Albuquerque, New Mexico. And, through their church, Desmangles and his wife, Gertrude, work with refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Haiti, helping them acculturate to the United States.

“It’s an interesting life,” says Desmangles. He says his 40 years at Trinity were good to him. “I had the opportunity to teach some very fine students. I learned from them; they enriched my life.”

When asked if he foresees a time when he will stop writing and research, Desmangles seems to speak for himself and his colleagues when he says, “I don’t think of it. For now, it’s full speed ahead.”