Instructor: Chris Nadon, Associate Professor of Political Science, Claremont McKenna College

Course Outline and Texts:

Part I — The contemporary doctrine of Separation of Church and State in America

Supreme court cases: Reynolds v. U.S. Everson v. Board of Education. Walz v. Tax Commission. Zorach v. Clauson. Torcaso v. Watkins. [Do our political institutions presuppose the existence of a Supreme Being? What are the foundations of our rights?]

Part II – Jefferson and the Wall of Separation

Jefferson, “Declaration of Independence,” Letter to Weightman, 24 June 1826; Notes on the State of Virginia, 17-18; “A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom.” “No Politics in the Pulpit;” “Freedom of Religion at the University of Virginia;” Letter to Mrs. Adams, 11 Sept 1804; Letter to Rush, 21 Apr 1803. Madison, Letter to Jefferson, 8 Feb. 1825.

Mayflower Compact. Roger Williams, “Mr. Cotton’s Letter Lately Printed,

Examined and Answered.”

Part III –Modern Natural Right and the Bible

The Christian doctrine of separation: selections from Augustine and Calvin.

Hobbes, Leviathan, Behemoth.

Contemporary reactions to Hobbes, esp. from divines.

Genesis, Samuel I and II.

Part IV — Separation of Church and State

The secular doctrine (Protestant England): Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration. Jonas Proast’s resonse.

The secular doctrine (Catholic France): Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws; Bossuet, Politics Drawn from the Very Words of Scripture.

Part V — America Reconsidered

Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance. Tocqueville, selections form Democracy in America.

Part VI – God is Dead and the problem of the Last Man

Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil.

Motive

For the most part, this course has its origins as a response to Bernard Lewis’ What Went Wrong.” Written before but published after September 11th, the book seeks to explain to a Western audience the specific historical and theoretical difficulties that stand in the way of modernization in Middle Eastern countries. Religion plays a leading role as indicated by the work’s subtitle – The Clash between Islam and Modernity in the Middle East – but in manner somewhat more complicated than usually presented. One of Lewis’ more provocative (and I think largely ignored) arguments is that the introduction of the office of Chief Mufti under the Ottomans and the similar institution of the ayatollahs in Iran introduced an “ecclesiastical hierarchy” unknown to “classical Islam,” and which in fact represents a “Christianizing” of Islam.1 So what the West or Modernity faces in Islamic radicalism and theocracy is not so much an Islamic other as it is a reconfigured version of itself. Lewis, as a partisan of “the old pluralistic order, multi-denominational and polyethnic” which he claims was characteristic of classical Islam, laments its Christian infection. But his diagnosis also holds out the hope of a cure, the same cure devised long ago in the West. In other words, having caught “a Christian disease,” it might be good for Islamic world to consider “a Christian remedy.”

I’m in no position to judge the validity of Lewis’ characterization of the Islamic world. But What Went Wrong contains within it another more or less explicit work that we might call What Went Right. One of the things he thinks went right in the West is the emergence of “secularism and civil society.” According to Lewis, this could happen in Europe because Christianity, unlike Islam or Judaism, distinguishes between political and religious authorities (“Render therefore unto Caesar. . . ), something which allows for

1 What Went Wrong, 108-109. “The office of ayatollah is a creation of the nineteenth century; the rule of Khomeini and of his successor as ‘supreme jurist’ an innovation of the twentieth” (114).

their ultimate separation.2 Indeed, the separation of church and state is the “Christian remedy” for the “Christian disease” of religious intolerance that Lewis now thinks the Islamic world needs to apply to itself. But, granted that the separation of church and state is a distinctive and distinctively liberating doctrine, is it right to conceive of it as necessarily or essentially a Christian doctrine? If in fact it is, then there is something especially chimerical about Lewis’ hope to apply it in the Islamic world (the rhetorical difficulties alone seem insurmountable). And, of course, the self-understanding of the West is also at stake in this question. If secularism is an essentially Christian phenomenon, then to what extent is it actually secular? The current conflict between the West and Islam seems to provide a real motive for us to look back at just how the doctrine of the separation of church and state managed to assert itself.

Pedagogic Difficulties and the American Context

It seems to me that the biggest difficulty in teaching a course on the separation of church and state is the fact that we all live within a secular political order, and that we do so more or less happily. We agree with the implicit sub-title of Lewis’ book that something in the West did go right, and a large part of that something is the separation of church and state. But this means that it is particularly difficulty for us to enter into and understand the (pre-modern) perspective that considers religion and politics to be necessarily intertwined, if not indistinguishable. I’ve tried to address this problem by beginning the course with some US Supreme Court decisions that deal with the separation of church and State and raise the question of the relation of religion to our rights. Everson v. Board of Education (1946) serves to inject the language of a “high and 2 Want Went Wrong, 97, 113-116.

impregnable wall” between church and state, and revives Jefferson’s “Bill for Establishing Religious Liberty” and Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance” as providing some historical precedents for the policy. Zorach v. Clauson (1951) asserts that “We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.” Yet by Torcaso v. Watkins, the Court, following the internal logic of Everson, holds that the government must be neutral between those religions that are based on a belief in the existence of God and those that are not, as well as between religion and non-religion. Are these claims compatible?

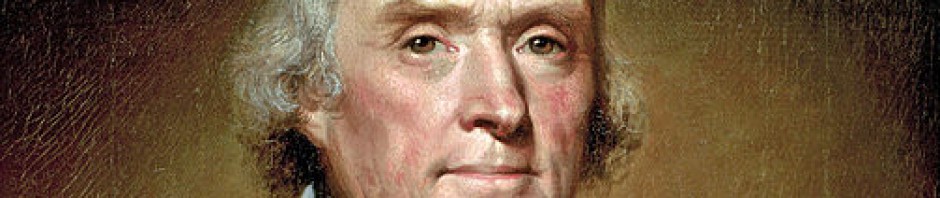

Thomas Jefferson gave sustained thought to the relation between religion and political liberties and rights, and current American jurisprudence owes much to his writings, especially the Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom. Yet we find in him an ambiguity about our rights and our religion(s) similar to that found in current Court cases. In the Declaration and Notes on the State of Virginia the connection between them seems to be relatively clear: men are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights;” and “can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath?” But there are other passages and letters in which Jefferson seems to look forward to the waning and perhaps even disappearance of religious belief. Hobbes

Again, my primary reason for starting with the American context is to try to come up with way

s of showing that the separation between church and state can never be so neat, clean and impermeable as the rhetoric of a wall of separation implies, and therefore to make other ways of handling relations between church and state more plausible. But I’d also like to raise the question of the theoretical and possibly theological foundation of liberal rights. I take Hobbes to be the originator of modern natural rights doctrines, or at least of the strand of natural rights that ultimately leads to democratic constitutionalism. And the centerpiece of the course will focus on his efforts to devise a commonwealth immune to the disease of religiously inspired tumults by subjecting them to political control, while in turn expelling from the political realm all claims based on transcendence.

Hobbes is adamantly against the separation of church and state.3 One can accordingly use his diagnosis of its pathologies from both the Leviathan and Behemoth to introduce the traditional Christian understandings of the separation as one based on different functions within a religious whole rather than on theoretically distinct spheres (secular and religious) of human activity or aspirations. Selections from Augustine’s City of God and Calvin’s Institutes are useful (and easily available) for highlighting Hobbes’ points of departure. But I’d also like to read some responses to the Leviathan from Hobbes’ contemporaries. There is now available a useful and not so expensive collection.4 Again, I’m interested in doing this as a way of combating the influence on us of Hobbes’ great practical success, not so much as a political theorist (after all, no

3 “All other men distinguish between the Church and the Commonwealth: Onely

T.H. maketh them to be one and the same thing,” John Bramhall, The Catching of Leviathan, or the Great Whale: Demonstrating, out of Mr. Hobs own Works, That no man who is thoroughly an Hobbist, can be a good Christian, or a good Commonwealths man, or reconcile himself to himself (1658).

4 G.A.J. Rogers, editor, Leviathan: Contemporary Responses to the Political Theory of Thomas Hobbes (Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1995), 126.

sovereign ever picked up the Leviathan on his own and implemented its prescriptions, as he seems to have hoped for), but as a political theologian. A fair amount of recent scholarship on Hobbes’ focuses on his “religiosity,” a term that seems to me thinkable only if one has swallowed whole the theology he presents in Book III of the Leviathan. Contemporary responses to that part of the work are therefore helpful in seeing the extent to which it contained innovations.

Another way of bringing out what is new in Hobbes might be to contrast his overall “anthropology” with that contained in the Bible, or at least in the Old Testament. First of all, having students read the first 10 chapters of Genesis, as well as selections from Exodus and Samuel I and II, allows them to judge for themselves the character of some of Hobbes’ uses of Biblical verses. But it also exposes them to a way of looking at the world and man’s place in it that calls into question Hobbes’ embrace of technology and modern science, to say nothing of his portrait of forsaken lot.

Locke and Montesquieu

Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration has been historically the most influential formulation of the modern doctrine of separation of church and state, not least of all in the 20th century when in the aftermath of World War II when UNESCO sponsored its translation and publication in some 20 languages. [There is probably also some connection worth exploring between the new recourse to Locke through Jefferson in postwar Supreme Court jurisprudence and the emergence of the fascist and communist totalitarianisms that play such a large role in determining modern liberalism’s self-understanding.] Locke, like Hobbes, seems to me to wish to submit religion to political control. But he sees Hobbesian absolutism as likely to be ineffective at controlling religious dissent, or, if successful, a greater threat to political liberty than claims based explicitly on theology. To respond to this problem, it seems to me that Locke restores or restate the Christian distinction between and separation of church and state that Hobbes rejected, but that he does so on principles much closer to Hobbes than the Christians. With Locke one can also begin to see the intimate connection between the separation of church and state and the modern constitutionalism that opposes political absolutism in the name of limited government with its separation of powers. He also shows how the separation of church and state can allow the state to make use of religion for civil purposes without necessarily having to establish a civil religion. The success of this project obviously owed much to the context of explicitly Protestant political thought. Among the issues I’d like to raise in reading Locke’s Letter is the extent to which it is based upon or takes advantage of Protestant theology. Is the separation of church and state dependent not only on Christian but more specifically Protestant premises? If so, does this undercut the universalist pretensions of the liberalism that seems so much to depend upon it?

Montesquieu helps in thinking about these issues inasmuch as he seems to be advocating some form of English constitutionalism but within a political and religious context where recourse to the contractualist premises of State of Nature doctrines and man’s original liberty result in charges of Protestantism, a sect no longer officially tolerated in the realm of the most Catholic kings. Accordingly, one finds a much less juridical or doctrinaire approach to the separation of church and state in Montesquieu, which, for this very reason, might well be of greater theoretical interest and practical use in confronting the present day situation.

American Reconsidered

Having made this historical travel-trip, I’d like to return to reconsider the place of religion in America as Tocqueville describes it. Tocqueville’s account of religion is related to his account of the vices of democratic society and is at least in part governed by the role he thinks religion can play in ameliorating them. But he is of particular interest for this course because he gives an account of how the separation of church and state works within a democratic without recourse to the judiciary. Given the prominent role the judiciary plays in enforcing the separation of church and state today, Tocqueville helps us to think about the non-governmental or informal mechanisms for handling religious diversity that antedate our approach. He also provides much material for thinking about the ways in which democratic societies and sentiments act to transform religion.

Post Script?

Tocqueville is somewhat pessimistic, I think, about the fate of human dignity in what he takes to be the inevitable democratic future of mankind. These concerns are pushed to an extreme in Nietzsche and explicitly connected to the destruction of genuine religion in and by modern democratic societies. Reading his account of the Last Man in Zarathustra, along with some selections from Beyond Good and Evil, might allow one to consider whether the contemporary fundamentalism (in its Islamic as well as other forms) is perhaps as much a post-Modern, as opposed to a pre-Modern, phenomenon. It might well then be, as Lewis contends, a typically Western phenomenon, yet without being at the same time essentially Christian or “Christianized.”