According to the Connecticut State Department of Education, both magnet and charter schools were founded on the basis of creating environments designed to “reduce racial, ethnic, and economic isolation.” However, of the two, only magnet schools are actually required to maintain a racial balance with the legislation passed in the Sheff vs. O’Neill case, whereas it is merely a suggestion for charter schools. In our essay, we look to past school enrollment data to reveal the importance of having this defined standard of reduced isolation, and how the presence of this guideline is more effective at integrating schools when strictly employed as in magnet schools than when simply encouraged as in charters. What is the big deal about having racial, ethnic, and economic integration in school populations anyways? The importance of integrated environments is highlighted by indisputable data regarding the higher academic achievement and increased social awareness of minority students educated in diverse environments. Integration not only leads to a “dramatic decrease in discriminatory attitudes and prejudices,” 1 but also it is crucial because “children from socioeconomically deprived families do better academically when they are integrated with children of higher socioeconomic status and better-educated families” 2. Looking at recent school enrollment data, we have found that a larger number of magnet schools have integrated student bodies than do charters, even with the 2013 revision of the definition of Sheff’s “reduced isolation.” Should charters be held to a similar, strictly defined standard for creating environments of reduced isolation as magnets are held to Sheff, we strongly believe that they too can have more integrated student bodies.

Magnets Versus Charters

Magnet schools are public schools that operate under “a local or regional school district, a regional educational service center, or a cooperative arrangement involving two or more districts” 3. Magnets have two main goals: to reduce racial, ethnic and economic isolation and to offer curricula that encourage and support educational improvement and achievement 4. The magnet schools we have chosen to focus on in this essay are those that participate in the Sheff integration settlements and specifically abide by the clearly defined standards for environments of reduced isolation. Because schools were not effectively desegregating and thus perpetuating unequal education opportunities, Elizabeth Horton Sheff and several other families filed a lawsuit in 1989 against the governor at the time, William O’Neill, demanding the end of isolated school environments. The plaintiffs succeeded after a long trial process, leading to a series of legal settlements and remedies aimed at increasing integration 5. In 2003, the first Sheff Stipulation and Proposed Order went into effect to rectify the Hartford schools’ violation of the Connecticut Constitutional order to reduce the racial, ethnic and socioeconomic isolation 6. Remedies to the Sheff legislation proposed benchmarks to enhance incentives and promote reduced isolation. If magnet schools fail to meet these guidelines, they risk losing grant funding 7. In 2008, the order required that magnets enroll between 25% and 75% minority students, defined as non-white students 8. In 2013, the range remained the same, but the definition of minority changed to only Black and Hispanic students 9. In 2013, Sheff included a section calling for the enrollment of at least 44% Hartford-resident minorities in any school participating in Sheff’s reduced-isolation goals 10. Most recently, Sheff has increased that requirement to 47.5% 11. Together these two clearly defined and measurable standards function to increase integration, achieving the primary goal of magnet schools.

Charter schools, on the other hand, are public schools “that operate independently of local and regional boards of education” with a goal “to reduce racial, ethnic and economic isolation” 12. With this idea at the forefront, charters establish their own methods and standards for achieving their goals. Charters abide by the Connecticut State Statute, which is riddled with vague language allowing charters to function with flexible accountability. This raises concerns for the incentives of charters and their goal of fostering diverse environments. When approving a charter, the “State Board of Education shall consider the effect of the proposed charter school on the reduction of racial, ethnic and economic isolation in the region in which it is to be located” 13. Merely “considering” something is meaningless – the legislation does not hold charters accountable to any kind of consequence if they do not successfully reduce isolation. Charters can be placed on probation if they fail to “achieve measurable progress in reducing racial, ethnic and economic isolation” 14. The question here is: what qualifies as measurable progress when there is no quantifiable value provided? Much like “considering,” “measurable progress” provides no substantial meaning because it is a subjective term, whereby charters decide on their own ratio of minority to non-minority students. They are then held only to their own personal standard for reduced isolation. While the State “may deny an application for the renewal of a charter,” they are not required to do so, thus charters will not necessarily be punished for a failure to comply with state regulations 15. The issue with this type of language is that while the statute does require charters to actively work towards integration, it provides no specific boundaries or definite consequences on which to hold them accountable.

The Sheff Standard: Old and New

In an attempt to reduce racially isolated schools, Sheff settlements outline requirements for schools to be considered desegregated. In 2008, Sheff categorized reduced isolation as schools whose minority percentage fell between 25%-75% of total enrollment 16. Minority was defined as non-white students, including Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, and Pacific Islander. Under this standard, about a third of magnets failed to comply. While it is much more common for schools to fail meeting reduced isolation standards because of an over enrollment of minority students, two of these noncompliant magnet schools faced the opposite issue – their failure to meet compliance stemmed from an overwhelming majority of white students. The frequency of hyper segregated environments of minority students can be attributed to the “niche market approach,” where schools and their administrators target low-income and minority groups to serve populations with the greatest need 17. By enrolling a larger number of minority students than of white, the schools achieve their goals of reaching more disadvantaged communities. However this approach proves to be far more detrimental to those disadvantaged students; educating them in a racially and economically segregated environment seems to do more harm than good.

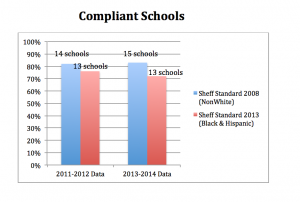

In 2013 Sheff amended its reduced isolation standards to refer solely to students identifying as any part Black or Hispanic 18. Under this new definition of minority, the number of non-compliant magnets in the 2013-2014 school year was cut in half, dropping from 22 schools to 11. Had the definition remained unchanged, 18 magnet schools would have been noncompliant in 2013-2014 (compared to the 11 noncompliant schools under Sheff’s 2013 standard), showing little to no significant change from past years. Furthermore, of those 18 magnets that failed to meet Sheff’s 2008 standards, 8 of them became compliant under Sheff’s revised standards in 2013 without having to alter their student enrollment.

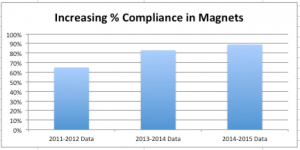

The annual enrollment data shows a consistent increase in compliance; by holding magnets to a measurable standard of reduced isolation, schools are held accountable and given real incentives to foster integrated student bodies. When counting only Black and/or Hispanic students towards reduced isolation, 83% of the magnets (52 out of 63 schools) successfully achieved Sheff compliance, a significant increase from its original 65% of compliant schools (41 out of 63 schools) in the 2011-2012 school year, using the previous definition of minority. Looking at the most recent school enrollment data for magnet schools reveals only 5 out of 45 listed schools out of compliance with Sheff standards, which further increases the percentage to 89% compliant.

It is important to acknowledge, however, that the way the word “minority” is defined has immense power in its ability to influence future demographics and enrollment standards in schools. Simply changing the definition for reduced isolation had a significant impact on whether or not magnet schools remained compliant with the racial standards set by Sheff. Under the original Sheff standard, defining “minority” as non-white, these schools would not have been in compliance. However, the updated definition of minority automatically puts these schools in compliance without any active effort to adjust racial enrollment. Thus, while an increasing number of schools were considered desegregated, the racial distribution for some schools changed minimally or not at all. A possible explanation for this might be that the Sheff settlements were attempting to reach students most in need of reduced isolation environments. By altering the definition, Sheff’s integration policy better served its purpose to increase diversity and created more opportunities for Black and Hispanic students. Regardless, a significant portion of these newly compliant schools did in fact make an active effort to reduce isolation, reinforcing the idea that this imposed standard of compliance encourages magnet schools to diversify and become compliant with Sheff standards.

What If?: Applying Sheff to Charters

In his original proposal for charters, Albert Shanker emphasized the necessity of reduced isolation environments for promoting social cohesion and high achievement. However, as more states adopted charter school legislation, there emerged an unexpected divergence from integration. Charter advocates and administrators chose instead to cater to niche markets and target immigrant populations as a way to “promote intercultural competence” and serve students “who are demonstrably in need of better schools” 19. Despite veering from Shanker’s original plan, charters still hold integration as one of their main goals. The Sheff reduced isolation standard is currently only exercised by magnets, which is not out of exclusivity within the legislation, but rather because other types of schools have chosen not to participate. In the Sheff legislation, the state agreed to incorporate a variety of programs, some of which include “charter school initiatives, state technical high schools and vocational agriculture programs, and other new and progressive initiatives,” that could, if they chose, be considered a part of the reduced isolation goal 20. Participating in this goal would allow the state to count the school in their total number of integrated schools, as well as make the school eligible for funding. Given that charters were designed to promote diversity, the Sheff standard of integration appears to directly align with their mission. However, charters have yet to act in accordance with the Sheff legislation; instead, they follow their own, more lenient integration guidelines as previously discussed.

Without a concrete and measurable unit for integration, charters can often neglect entirely this goal of diversity within their student enrollment. A lack in standard also creates more difficulty in determining which charters are succeeding or failing to create diverse and integrated environments. In order to test how integrated Connecticut charter schools were, we applied the new Sheff reduced isolation standard to charter schools from the 2013-2014 school year. We found that only 28% (5 out of 18) would be compliant with reduced isolation, compared to the 89% of magnets currently in compliance. While the change in Sheff’s definition of reduced isolation functioned to increase integration in magnets, applying this new standard to charters results in a decrease of compliant schools from 15 to 13. This reverse effect demonstrates that charters are failing to create opportunities for Black and Hispanic students who are in most need of integrated environments. Based on this disparity, we would argue that magnets are far more successful than are charters in creating environments of reduced isolation, a difference that is rooted in the strictly defined integration standard that magnets, but not charters, are held accountable to.

So why, then, do charters not adopt the Sheff standards? When our seminar spoke with the authors of A Smarter Charter, Kahlenberg and Potter explained that such a set standard was not in the nature of charters. Placing specific criteria or regulations on charters goes against Albert Shanker’s initial vision of charters as laboratory schools. For Shanker, charter schools were to function as experiments with varying approaches and curricula to discover what works best for all students 21. Charters do not want to hinder or bind themselves by requiring a standard for racial balance and integration because perhaps it is not the best way to educate its students. An education system built on freedom of exploration strives to hold on to that independence and self-governance. But while they exercise their freedom, charters fail to produce the rich and diverse environments Shanker had hoped would come naturally. It is this kind of integrated environment that promotes the highest achievement for students of low-income or minority backgrounds, one that magnets are required to ascribe to and charters are not. If charters were held to a similar standard as are magnets, it would increase their incentive and strengthen their dedication to create more diverse and integrated school environments.

Notes:

- Kahlenberg, R. D., & Potter, H. (2014). A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education. New York: Teachers College Press. p. 55

- Ibid 9.

- Cotto, R. & Feder, K. (2014). Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs. Connecticut Voices for Children. New Haven, CT. p. 6

- Ibid 6.

- Sheff v. O’Neill, 238 Conn. 1 – Conn:Supreme Court 1996.

- Sheff v O’Neill. “Stipulation and Proposed Order [Remedy Phase III].” Superior Court: Complex Litigation Docket at Hartford, CT, HHD-X07-CV89-4026240-S, December 13, 2013. p. 1 https://www.dropbox.com/s/jrdbk0an15t398d/Sheff20131213PhaseIII.pdf?dl=0.

- Cotto, R. & Feder, K. (2014). Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs. Connecticut Voices for Children. New Haven, CT. p. 6

- Sheff v O’Neill. “Stipulation and Proposed Order [Remedy Phase II].” Superior Court: Complex Litigation Docket at Hartford, CT, HHD-X07-CV89-4026240-S, April 4, 2008. p. 3. http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp_archives/19/.

- Sheff v O’Neill. “Stipulation and Proposed Order [Remedy Phase III].” Superior Court: Complex Litigation Docket at Hartford, CT, HHD-X07-CV89-4026240-S, December 13, 2013. p. 5 https://www.dropbox.com/s/jrdbk0an15t398d/Sheff20131213PhaseIII.pdf?dl=0.

- Ibid 5.

- Sheff v O’Neill. “Stipulation and Proposed Order [Remedy Phase IV].” Superior Court: Complex Litigation Docket at Hartford, CT, HHD-X07-CV89-4026240-S, February 23, 2015. p. 2 http://www.sheffmovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/sheff-settlement-2.23.15.pdf.

- Cotto, R. & Feder, K. (2014). Choice Watch: Diversity and Access in Connecticut’s School Choice Programs. Connecticut Voices for Children. New Haven, CT. p. 6

- General Statutes of Connecticut (2015). Chapter 164 – Educational Opportunities, Section 10-66bb, http://search.cga.state.ct.us/sur/chap_164.htm#sec_10-66bb

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sheff v O’Neill. “Stipulation and Proposed Order [Remedy Phase II].” Superior Court: Complex Litigation Docket at Hartford, CT, HHD-X07-CV89-4026240-S, April 4, 2008. p. 3 http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp_archives/19/.

- Kahlenberg, R. D., & Potter, H. (2014). A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education. New York: Teachers College Press. p. 18

- Sheff v O’Neill. “Stipulation and Proposed Order [Remedy Phase III].” Superior Court: Complex Litigation Docket at Hartford, CT, HHD-X07-CV89-4026240-S, December 13, 2013. p. 5. https://www.dropbox.com/s/jrdbk0an15t398d/Sheff20131213PhaseIII.pdf?dl=0.

- Kahlenberg, R. D., & Potter, H. (2014). A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education. New York: Teachers College Press. p. 18-19.

- Sheff v O’Neill. “Stipulation and Proposed Order [Remedy Phase III].” Superior Court: Complex Litigation Docket at Hartford, CT, HHD-X07-CV89-4026240-S, December 13, 2013. p. 2. https://www.dropbox.com/s/jrdbk0an15t398d/Sheff20131213PhaseIII.pdf?dl=0.

- Kahlenberg, R. D., & Potter, H. (2014). A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education. New York: Teachers College Press. p. 7.