The presence of charter schools in cities throughout the United States continues to increase as families become more dissatisfied with traditional public schooling and look for alternatives. The first charter school opened in Minnesota in 1992 (Cavanagh), and since then they have rapidly expanded across the nation. Charter schools have been highly criticized by education reformers who don’t believe that they are a long-term solution to ensuring all children have access to a public school education. However, they are not the only alternative to standard public schooling in urban areas. Catholic schools have provided students with a quality education long before charter schools were established, and pride themselves on having the task of “transmitting to students, by various means, the specific norms, values, and beliefs of the Catholic faith” (Donlevy 106). However, the emergence of charter schools has significantly changed the education sector and affected the existence of private, specifically Catholic, schools.

By reviewing various studies that address the connection between charter schools and Catholic schools on a national level, there is enough evidence to suggest that the growth of the former has negatively affected enrollment rates of the latter. This paper will explore the relationship further and address reasons to explain how, and why, the charter school movement has caused Catholic schools to decline over the past two decades. This association will first be looked at on a national level, and then locally by focusing on Jumoke Academy, a charter school in Hartford, Connecticut that used to be called St. Justin’s School and was run by the Hartford Archdiocese. However, by examining this specific case in Hartford, it is evident that arriving at a definite conclusion is not as straightforward as the national relationship makes it seem. This paper addresses the complex nature of the education system by taking into consideration that the national findings do not line up perfectly with this specific, Hartford-based example.

Researchers have conducted several studies in the past year that focus on how the rise of the charter school movement has affected Catholic schools. In their study entitled “Catholic Schools, Charter Schools, and Urban Neighborhoods,” Margaret Brinig and Nicole Garnett find a close relationship between the rise of charter schools and decrease of Catholic schools in urban areas. Though they limit their study to Chicago, they bring up some important overall distinctions between the two different types of schools, which are helpful in understanding how they are connected at a national level. According to their research, the number of Catholic schools nationwide was at an all time high in the middle of the twentieth century. However, by the late 1960s, this number began to decline due to financial reasons. The study states that “religious vocations plummeted at the same time that Catholics suburbanized en masse, causing parochial schools to experience dramatic increases in labor costs just as collection revenues declined precipitously” (Brinig & Garnett 35). These academic institutions, which are run and funded by the Archdiocese, began to experience difficulties providing adequate resources and training to their teachers and students. It also discusses the priests’, who were historically responsible for operating the schools, change in perspective. They began to view these Catholic schools, which no longer just served Catholic students, as “unnecessary burden[s]” (35), which is a factor that can be linked to a decline in academic quality. Nationally speaking, financial difficulties caused Catholic schools to decrease in academic caliber and as a result, became less desirable to families compared to what charter schools could offer.

To provide some contextualization of the relevancy of this comparison between Catholic schools and charter schools, Brinig and Garnett also give an overview of charter schools’ history in the United States. They suggest that the increase in popularity is because they have several of the attributes of private schools, yet are “schools of choice” and entirely free. The article also brings up a point of distinction between charter schools and other schools: often times, charters are “more accountable than private schools and, arguably, even more than traditional public schools, because underperforming charter schools are more likely to be closed” (37). This specific piece of information is particularly relevant to the overall argument of this paper because of the clear relationship it establishes between these two types of schools. When given a choice between a costly private school that is not held accountable for its results, and a free charter school that works hard to ensure that it is meeting national standards and adequately preparing its students, it can be assumed that most parents would be inclined to choose the latter.

It is significant to notice that this connection between the decline of Catholic schools and rise of charter schools has just begun to be studied by researchers. Brinig and Garnett published their study in January 1, 2012, and since then there have been several other studies that address this relationship. It is likely that the explanation for this is the upsurge of new research surrounding charter schools as they are at the forefront of the school choice movement. Richard Buddin discusses the impact charter schools have had on private schools as well as traditional public schools in his study, published in August 28, 2012. Before closely looking at Buddin’s findings, it is important to clarify how his research is relevant to the development of this argument. He first divides up the schools he looks at into the categories: traditional public school, charter, private, Catholic, other religious, and nonsectarian, and some of his explanations are limited to how the emergence of charter schools has decreased enrollment rates in all private schools and traditional public schools. However, early on into his study he clarifies his objective by stating, “the enrollment patterns across Catholic, other religious, and nonsectarian schools are similar to those for all private schools; that is, each type of school is more common in urban than non-urban areas and each type is more common at lower-grade levels” (Buddin 16).

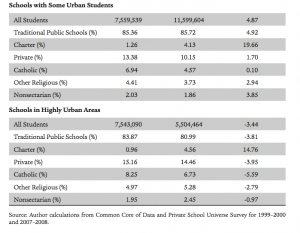

For the purposes of this research, the overall argument is not limited to a particular grade-level. Buddin, however, goes into greater detail, and though some of his research surpasses the limits of this paper, his findings are in-line with the complete thesis because of his focus on charter schools’ impact on private schools (which includes Catholic schools) in urban neighborhoods. The basis for his observations stems from a study entitled “Changes in School Type by Urban Enrollment Status,” which examines the annual growth in enrollment percentage from 2000 to 2008 at the different school categories previously mentioned. The chart below highlights some of Buddin’s most important and relevant findings that help explain this relationship:

Though his study breaks the nation’s student population into four models: overall patterns of student enrollment, schools in non-urban areas, schools in some urban areas, and schools that are highly urban, for the purposes of this analysis only the charts that demonstrate “schools with some urban students” and “schools in highly urban areas” are included. Buddin differentiates between these two categories with the condition that to be a highly urban area, at least 50% of the students must live in a large city (19).

Most notable in this study is the difference in growth between charter schools and Catholic schools over the eight-year span. In highly urban areas, charter school percentage increased by 14.76%, from .96% of the student pool in 2000 to 4.56% in 2008. However, Catholic school enrollment declined by 5.59%, from 8.25% to 6.73% in 2008. The study also highlights an interesting difference between the growths of traditional public schools and charter schools; despite a growth in charter schools, the percentage of students enrolled in traditional public schools declined by 3.81%. This statistic strengthens the argument that students in urban and highly urban areas are choosing to enroll in charter schools over Catholic schools; they are not simply dropping out of Catholic schools to attend any public school—they are opting for charter schools over traditional public schools. If the reason students were avoiding Catholic schools was merely because of tuition costs or the faith-based curriculum that exists in these institutions, it would be logical to assume that the enrollment percentage would increase for traditional public schools as well. Instead however, all other numbers have decreased over the eight-year period, while the enrollment in charter schools is the only number to have gone up.

This study brings up other interesting points that help to describe the relationship between charters and Catholic schools nationwide. Buddin points out “in highly urban areas, private schools contribute 32, 23, and 15% of charter elementary, middle, and high school enrollments” (23). Keeping in mind that when he refers to “private schools” he is including Catholic schools, this point is made exceedingly relevant to the overall argument of this paper. There are several reasons to explain why Catholic schools have decreased nationally and why they appear to be funneling their students into charter schools. Sean Cavanagh discusses the plummet in Catholic school enrollment in “Catholic Ed., K-12 Charters Squaring Off,” which was published in Education Week in August 2012. It is interesting to note that this analysis was also done in late 2012, again reinforcing the relative newness of interest in charter schools’ affect on the private education sector. The first similarity Cavanagh brings up between Catholic schools and charter schools is likeness in framework and design. Concrete examples he uses are the parallels in school missions, academic models, and the overall demographic of students both schools primarily serve (Cavanagh). The combination of the community-centered approach most charter school networks pride themselves on and absence of tuition makes enrolling in a charter school a popular and logical choice for many families in urban areas.

Cavanaugh’s argument is further strengthened by two compelling statistics he includes in his article. He writes, “Since 2000, 1,942 Catholic schools around the country have shut their doors, and enrollment has dropped by 621,583 students, to just over 2 million today, according to the National Catholic Educational Association. If that decline continues, charter enrollment will surpass that of Catholic Schools for the first time this academic year” (Cavanaugh). This data is from a study conducted by Sean Kennedy from the Lexington Institute, a think tank that has examined the Catholic and charter systems. Later in his article he states, “Today, some 5,600 charter schools, serving about 2 million students, operate in 41 states and the District of Columbia” (Cavanaugh). This prediction is further strengthened by a statistic Buddin inputs in his discussion of the charter school movement. He writes that “if trends continue, charter share in total enrollment will rise from 3.7% to 6.2% in 2016” (Buddin 23). These facts are significant and tremendously telling of the magnitude of the charter school movement and how its growth over the past two decades has, and will continue, to affect Catholic schools in the United States at a national level.

The three studies stated above provide enough evidence to conclude that there is a clear national trend that exists between the rise of charter schools and decline of Catholic schools. However, when applying this theory to a local example, the common causality appears to be less clear. According to a Hartford Courant article published in 1992, St. Justin’s School was the “last school in the Archdiocese of Hartford with a predominantly black enrollment attached to a predominantly black parish, [and] closed in 1989” (Renner). Eight years later, Jumoke Academy opened its doors in the same building St. Justin’s had occupied (Green). This example raises the questions: what was the site used for during this eight year gap, and is the relationship between this former Catholic school and currently operating charter school consistent with the aforementioned national trend? Brinig and Garett found that there were multiple situations in their study of Chicago where charter schools physically replaced Catholic schools; they noticed this fact in 14 schools that they researched (33). However, this is not enough evidence to support this one specific case in Hartford. The eight-year gap between St. Justin’s closing and Jumoke’s opening complicates the relationship and suggests that the closing of St. Justin’s School and opening of Jumoke Academy in the same building in 1997, might just be a coincidence.

Despite the ambiguities this example presents, there are some similarities to suggest that this relationship may be consistent, in some ways, with the national trends previously discussed. The same Hartford Courant article that discusses St. Justin’s closing also states, “In the three-county Hartford Archdiocese, Catholic school enrollment was 22,000 in the past school year, compared with 54,000 in 1964” (Renner). This goes to show that despite the overall generality of Buddin, Cavanaugh, and Brinig and Garnett’s studies, the national trends found in their studies are applicable in various ways to the city of Hartford. It is clear that the same decline in Catholic schools nationwide is also noticeable in this one specific region of study; Hartford was by no means immune to the effects of the charter school movement, though it is less evident whether the definite cause for St. Justin’s School’s closing was related to the upsurge of charter schools in the area as well.

Though the reasons behind this closing are not explicitly stated, many Catholic schools were forced to close because of financial difficulties or lack of resources. Although there is no concrete evidence to definitively provide an answer for why St. Justin’s School closed, newspaper articles from the Hartford Courant suggest that Jumoke Academy has, and continues to be, well-received by the Hartford community. In an article titled, “Jumoke Becoming an Achiever,” the charter school’s success is highlighted by the following line, “Now in its 11th year, the 325-student school is emerging as one of the better-run charters, taking in mostly poor black and Latino kids who, chosen by lottery, usually arrive well behind academically” (Simpson). The article goes on to praise the dedicated teaching staff, revamped curriculum, and longer school days as major factors in the school’s success. This example of Jumoke Academy demonstrates how complex the relationship between charter schools and Catholic schools truly is. Despite having a strong understanding of how this connection manifests itself on a national level, it cannot be seamlessly applied to the case of St. Justin’s School and Jumoke Academy.

On a national level, research indicates that a conclusion can be made in regards to the charter school movement’s affect on Catholic schools over the last twenty years. However, the specific example of St. Justin’s School and Jumoke Academy questions this relationship and suggests that there is not just one explanation for the closing of a Catholic school. The overall picture of this correlation becomes less clear when viewing it through both a national and local lens, but does not necessarily invalidate the understanding that, on a broader, national scale, there is an obvious connection between the rise of charter schools and decline of Catholic schools. Due to the relative newness of this research topic, it will be interesting to see how charter school growth continues to affect the future of Catholic schools in the United States.

Works Cited

Brinig, Margaret F., and Nicole Stelle Garnett. “Catholic Schools, Charter Schools, and Urban Neighborhoods.” The University of Chicago Law Review 79, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 31–57. doi:10.2307/41552894.

Buddin, Richard. “The Impact of Charter Schools on Public and Private School Enrollments.” Policy Analysis no. 707. Web. 28 August 2012

Cavanagh, Sean. “Catholic Ed. k-12 Charters Squaring Off.” Education Week 32.2 (2012): 1-13. Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 20 April 2013.

Donlevy, J. Kent. “Catholic Schools: The Inclusion of Non-Catholic Students.” Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne De L’éducation 27, no. 1 (January 1, 2002): 101–118. doi:10.2307/1602190.

Green, Rick, and Courant Staff Writer. “HARTFORD COULD BE LEFT WITHOUT, AS CHARTER SCHOOLS OPEN THIS FALL: [STATEWIDE Edition].” Hartford Courant. May 15, 1997, sec. MAIN (A).

Renner, Gerald, and Courant Religion Writer. “Schools Get Respect but Dozens Close Spirited Debate How Connecticut Catholics Are Struggling with Change Third of Five Parts Schools Get Respect but Many Close: [A Edition].” Hartford Courant. August 25, 1992, sec. MAIN (A).

Simpson, Stan, “JUMOKE BECOMING AN ACHIEVER [Corrected 08/03/07]. Hartford Courant. August 1, 2007, sec. CONNECTICUT.

This essay investigates the relationship between Catholic schools and charter schools since the 1990s, and argues that on a national level, charter growth has “negatively affected enrollment rates” of Catholic schools. The decision to include a local case study is wise, but the wording of the introductory thesis is hard to understand. Based on what you wrote in the body of the essay, perhaps a clearer way to present your argument might be something like this: Although national-level numerical data show Catholic school decline and charter school growth, one historical case study reveals that the closure of a Hartford parochial school was not directly caused by a competition with a charter school, which did not open until eight years later.

Good work on appropriate source materials for this essay. The analysis of Buddin’s chart thoughtfully considers alternative explanations and dismisses those that do not fit. But to be persuaded that urban students “are choosing to enroll in charter schools over Catholic schools,” I would need more direct evidence (such as numbers of charter school students who previously attended parochial schools, or who considered applying to both). That’s too high a standard of evidence for an Ed 300 essay, but worth mentioning because you understand other plausible explanations that could be operating behind the scenes here. For example, if Catholic families also tended to move from cities to suburbs during this period, that could explain the decline of parochial enrollments independently of charter school growth.

Some claims are not well supported, such as the one that states, “it can be assumed that most parents would choose. . .” Never assume that real people actually behave as rational choice theory dictates. Also, the essay states too strongly that “there is no concrete evidence to definitely provide an answer for why St. Justin’s School closed.” The evidence probably exists in the microfilm portion of the Hartford Courant (or the Archdiocese archives), but there was insufficient time for you to do that level of detailed research for an Ed 300 essay. Overall, I’m delighted you wrote on this topic, and you taught me to think about this complex issue in new ways.

My comments above are based on the Ed 300 research web-essay criteria:

http://commons.trincoll.edu/edreform/assignments/research-essay-process/