“Great schools come from great people” (Guggenheim, 1:43:48) is the beginning of Guggenheim’s analysis of eradicating our current broken school system as he navigates through various problems plaguing our schools such as lack of accountability, international competition with other countries, the school-to-prison pipeline, and namely, school choice as an evasion of the solution to the educational crisis. He focuses his documentary on four children throughout the United States, from various backgrounds and familial structures, who all were partaking in school choice by applying to different charter schools in the nation, and details the opportunities that these schools promise, however, are only given to a lucky few. As he illustrates, our current educational system lacks an urgency to educate all children equally and adequately and rather resorts to other practices instead of addressing the fundamental issues that create inequality within our schools and our society.

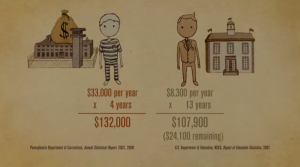

Of the captivating statistics that Guggenheim presents in the documentary, Waiting for “Superman”, the school-to-prison pipeline that the United States funds more than it does the schools of the nation’s children demonstrates that it is a deliberate institutional act that the country partakes in to prioritize prisons over schools, further illustrating a broken system. In an illustration depicting an incarcerated cartoon figure and a professional, educated cartoon figure, Guggenheim shows that the United States in fact funds prisons more than it does students. As his voice over describes, it costs the United States more money to have people in prisons for four years than it would to send students to private schools for from prekindergarten to senior year of high school. Beneath each image, the equation of the costs for each situation is totaled and and the difference between the costs is also calculated to illustrate to the viewer that a large sum of money is intentionally misplaced in correctional facilities rather than schools (Guggenheim, 25:19). As he further describes, many students in schools will later be incarcerated and schools serve as the mechanism to allow this to happen as schools deem certain students as liabilities and allow those students to slip through the hands of the educational system and land in a farther marginalized subset group of people. The inclusion of this particular statistic demonstrates an intentionality to penalize and exclude certain students from participating in society due to the lack of education and lack of rights that people have following incarceration. With the illustrations that hold a cartoon nature and playful element to them, Guggenheim eludes to this matter not being addressed as seriously as it should be despite its huge implications. As Guggenheim shows through this specific moment and throughout his documentary, the intention to actually educate all students equally and adequately must be present in order to fix this broken system or the cycle will continue.

Kahlenberg and Potter’s analysis of charter schools is not in concordance with Guggenheim’s assessment of charter schools as Kahlenberg and Potter believe that charter schools do little to improve the lives of students while Guggenheim says that charter schools, although unfair in nature, are often the only mechanism to give students a chance. Although Kahlenberg and Potter acknowledge that charter schools may provide students with opportunities not offered by traditional public schools, charter schools do not significantly benefit students as, “While there are excellent charter schools and there are also terrible ones, on average, charter students perform about the same as those in traditional public schools. In our view, the charter school movement, once brimming with tremendous promise, has lost its way” (Kahlenberg and Potter, 5). These authors believe that charter schools must be reimagined in order to meet the mission of Shanker, the originator of the charter school movement as these schools were meant to produce competitive, superior students and these schools have failed to do so. Guggenheim, however, disagrees that charter schools do not produce “better” students as through the examples of the four students applying to various charter schools nationwide, these schools are the only option for these students to succeed. He depicts these schools as the beginning towards social mobility because these schools have better resources and better teachers. These schools are vital in the livelihoods of these students because detrimental consequences occur when schools do not have the proper resources to educate students equally and effectively. Additionally, the inclusion of the statistics about the KIPP schools and their excellence, shows that Guggenheim believes that charter schools can achieve great results. Based on their own perceptions of charter schools and their supposed promises to students, Kahlenberg and Potter and Guggenheim think differently about charter schools and their ability to produce high achieving students.

Bibliography

Guggenheim, Davis. Waiting for “Superman.” 2010. Film.