Albert Einstein once said: “The only thing that interferes with my learning is my education.” This observation speaks to me on two profound levels: First, I was never able to discern the dispute between traditional and charter schools, despite working with charters for the past six summers. Secondly, as I searched for an entry-level position in education this year, the most visible job applications were an assortment of fast-track two-year teaching charter school initiatives. Through this paper, I intend to explore the fundamental role of the teacher, and how the dispute between traditional and charter schools has impacted the profession of teaching in America over time.

With a constantly oscillating pendulum from autonomy through accountability, continuity to competition, centralization, and decentralization then recentralization: America has spun a sticky web of education legislation that catches politicians, educators and families alike in a stalemate. How have charter schools effected America’s education today since they were first established in 1992? My research will address the particular effects of charter schools on the role of contemporary educators. Overall, this paper will examine the degeneration of the role of a teacher: specifically through teacher salaries, the charter school business-model, the further elevated status of school administrators and principals over teachers, and the perpetual prescription of teacher turnover-rates by attracting young teachers with energy and intellect, but also with a lack of incentives and experiential expertise to overcome the adversities of teaching in low-performing schools and low-income communities. Are we fixing old problems, or simply creating new ones?

The charter school movement was a rationale reaction to our evolving world, knowledge and education. My thesis is that, the charter school movement has been beneficial to the gaps in America’s education system since it was embraced in the 1990s, but is ultimately harmful to the fundamental occupation of today’s teacher. Charter schools are not the “silver bullet” for education, but they are the foundry alloy that’s clipping the issues within the system, while also polarizing pugnacious traditional and charter school advocates and leaders.1 Charter schools can’t fix America’s education inequalities without reconciling their model with traditional schools.

In 1960, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) was founded and formed in response to the perceived unfairness and mistreatment of teachers in America’s education system. In 1983, A Nation at Risk released what “was an impassioned plea to make our schools function in their core mission as academic institutions and to make our educational system live up to its ideals,” by upgrading teacher preparation and textbooks, raising education standards, improving curriculums and forcing educators to shift their styles of teaching.2 In 1992, Minnesota approved the first charter-school law,3 and in 1994, the Clinton Administration strongly supported and further encouraged states to pass charter laws. By 1998, Albert Shanker, the President of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) embraced the concept of charter schools, which mobilized their establishment across the country.

In 2002, President Bush’s distinctive domestic initiative, the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) created high-stakes standardized testing, which incentivized educators to spend less time teaching their curriculum and more time teaching to the test, leaving little time for genuine learning and ultimately, changed the nature of how traditional schools approached their standards and education.4 Then, from 2003 to 2007, Ray Budde’s vision in 1974 for a charter school model of education and the reorganization of school districts spread across the United States,5 which emphasized redefining education through innovative pedagogical practices, longer teaching hours, and overarching accountability, enforced by the principals and administrators of charter schools.

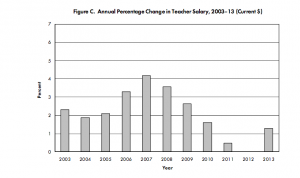

Through the charter school model, principals sign performance agreements and receive significant gains in their budget, along with discretionary spending. Reversing nearly a hundred years of hierarchical management, the principals of charter schools are given authority to retain, dismiss and even provide cash bonuses to their network support team members. Support team members are urged to: “follow up relentlessly when the system doesn’t respond or performs unsatisfactory, and ‘filter’ or ‘block’ other requests that may burden principals.”6 In turn, the charter school business-model is subtly degenerating the fundamental role of the teacher. “Teachers who leave charter schools are more dissatisfied with their terms of employment and the nature of the job than teachers who leave traditional public schools,”7 and when education is run like a business, it becomes a turnover factory for dissatisfied teachers, because “charters are free to set their own pay scales,”8 so while the income of a new charter school teacher is very low, about $14 per hour, and the income of a principal could be high or low, but either way, the stresses of both jobs are accelerated, along with teacher turnover-rates. Moreover, the National Education Association (NEA) reflects how changes in teachers’ salaries since 2003 and NCLB has been anything but stable. Since 2007, the annual salary of a teacher as progressively plummeted, and only recently raised:9

After decades of charter school experimentation, accountability has proven to be beneficial to achievement, opportunity and learning gaps in America’s education, but at what cost? As 2014 unfolds, traditional schoolteachers are experiencing further shifts in their curriculum from the Common Core and additional pressures from reformed pedagogy. But shouldn’t innovative thinking be collaborative and not competitive? Education cannot be run like a business because its goal isn’t to attain a profit; its goal is to educate. Teaching is an extraordinarily challenging occupation that’s constantly in flux. Charter schools are a result of shifts in legislation and make the role of a teacher progressively less appealing. Traditional schools do not advertise or promote, so young educators become cogs that turn the wheels of charter school agendas. The mission of charter schools is to “cultivate learners who use determination and innovative thinking to build a strong academic foundation in the 21st century learning environment.”10 But deceptively do not allow individual teachers to create any of their classrooms’ innovative thinking or practices; instead administrators and principals implement whatever “best practices” their organization embraces.

Charter schools have a very highly-defined set of criteria for what needs to be included in a lesson plan – making teaching into a strenuous series of systematic processes that artificially do not arise, but occur. Meanwhile, young aspiring teachers flock to the noble calls of charter schools, while experienced teachers avoid working in low-income, low-performing districts because the pay, responsibilities, treatment and management are notably unappealing. The position of a charter school teacher should be filled with highly experienced and tenured teachers who genuinely know what it means to invest themselves in a special group of students every year. But instead, education reform combats these kinds of teachers, and politicians are too scared to fully centralize or decentralize risks and invest in ideas that may not succeed.

“Unfortunate as it may be, schools have never been just about educating children. They are also about constructing social and political power. Real school reform must be about challenging it. Until we find the political will and vision to put social justice at the heart of the debate about public education, school reform will continue to be an exasperating tug of war with limited impact on the status quo.”11

Thus, it’s up to non-profit charter schools to try and equip this rope with excellent teachers every year, only their workforce brings the wrong mix of force. The core of education is centered on the teacher, and teaching should be similar to other social work like healthcare. Both occupations demand not only a commitment to their professions and undefined hours, but a commitment to others as well.

A brain surgeon is trained for at least eight years before they can touch a human brain, but an educator simply requires a background check before they can train a child’s mind. America’s best educators are attracted to postsecondary education, which also draws talent away from primary schools. The founder of the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ), Geoffrey Canada, expresses the need for early childhood education through “Baby College,”12 but according to an Occupational Employment and Wages from the U.S. Department of Labor: primary school teachers annually earn “$54,740,” while healthcare practitioners earned about “$93,320” annually, with an hourly medium of “$35.76.”13 In turn, America spends far more money on its healthcare than its education, meanwhile charter schools prescribe even less pay to their teachers.

Compensation differentials between schoolteachers and law enforcement officials are slightly alarming. Currently, police officers earn “$58,720” annually, in comparison to the “$54,740” of an average schoolteacher. There are two issues largely at play here: prison rates were increasing due to nonviolent crimes: “the federal prison population has reached record levels, that a high proportion of prisoners are non-violent drug offenders, and that racial disparities in sentencing and the proportion of lower-level drug offenders are increasing.”14 Although President Obama has largely addressed America’s clemency applications, it’s important to point out that our country currently pays its citizens more money to incarcerate people, than it does to teach them how to avoid incarceration. John Roman, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, said: “the biggest predictor of committing a criminal act is being young, male, and relatively low-skilled,”15 so could education be the cure for our country’s high crime and incarceration rates?

In regard to the educational implications of collegiate teacher salaries, the outstanding annual incomes of “postsecondary law ($122,280), health specialties ($105,880) and engineer ($102,880) teachers”16 should indicate that law, health and engineering are not being taught in primary schools when our youth clearly reflects a desire and demand to learn about these subjects later on. Why isn’t there a class on Law in middle school? America’s primary school education does not inform its students about how to follow the law. Instead, students receive an experiential trial and error education from police officers that sometimes inadvertently initiate self-perpetuating criminal records that progressively narrow career paths and futures.

The task of uprooting the ideology behind education reform is complex and nuanced, and charter schools may merely be a transitory route to turning around low-performing schools. But the problems of America’s education do not wholly rest within the minorities and cultural controversies that reform spurs and stirs: “The main reason Teach For America [TFA] teachers leave the classroom, Kopp said, is because they want to have a bigger impact,”17 a bigger impact than changing the trajectory of young minorities in struggling communities? Many TFA teachers find themselves as small parts of a bigger goal: and many of the most successful TFA graduates defer to becoming principals and administrators, not only because it’s a more impactful position with much better compensation, but also because the program ultimately renders the role of a teacher as undesirable: “nearly two-thirds (60.5%) of TFA teachers continue as public school teachers beyond their two-year commitment.”18 Some charter programs are proving they are better than TFA and Achievement First’s two-year-turnover conveyor belts, but only by about another two years: “Other charter networks have similar career arcs for teachers. At Success Academy Charter Schools, a chain run by Eva S. Moskowitz, a former New York City councilwoman, the average is about four years in the classroom. KIPP, one of the country’s best known and largest charter operators, with 141 schools in 20 states, also keeps teachers in classrooms for an average of about four years.”19 Daniel Lindley makes an insightful point about this:

“Teachers go through three stages in learning the craft. The first stage, the first full year of teaching, is just learning to be comfortable in a roomful of adolescents. The second stage, typically the second year, is teaching, with some success, the given curriculum. The third stage, which can begin in the third year and shouldn’t end, is teaching shaped by the creativity and originality of the teacher herself. Most of the ‘short-timers’ will never reach the third stage. No wonder so many leave after too short a time.”20

The result, teachers who truly love teaching become or try to become administrators and principals, potentially excellent educators traditionally flee and maybe a few of them get fired in public schools.

Charter schools are improving the quality of education in low-income communities and bridging gaps in our education, but they are also harming the overall occupation of the teacher. The charter school-model embodies teaching as a physical and financial sacrificial occupation, and reform is against the odds of limited resources in communities with economic disparities.

“Over the past several decades, the most elite sector of higher education has become more selective—and expensive—than ever. David L. Kirp writes that ‘even as higher education has become more stratified at the top, it has also become more widely available … on the lower rungs of the academic ladder, where what matters are money and enrollment figures, not prestige.’”21

However, the prestige and experiential credentials of a teacher should be paramount, it’s what makes education successful. What would it be like to employ new, but more thoroughly trained teachers at high-performing schools with intellectually curious students who encourage education; then employ highly-experienced teachers in low-performing schools with less motivated students who are struggling under the pressures of poverty, but maintained both of their current salaries?

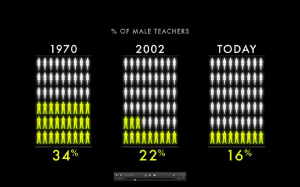

Innovative ideas like charter schools promote callings that attract generations thinking about how rapidly the world is changing, and how we must respond and adapt to these changes and rise above adversity. Failing schools should have the funds to attract the most high-performing teachers. However, the charter school movement targets less experienced, and more aspiring educators to transform communities and contribute to charter mission statements and statistical success, at the cost of uninspiring teachers through meager wages, extended hours, and most importantly, a culture of teachers who tour their time. Today’s education system attracts “16%”22 of males at a declining rate:

Traditional schooling initially made teaching appealing to women, while charters, to youth: and instead of protecting our country’s women and children, we’re sending them into schools with low-wages, long hours and little experience, and then pressuring them to outperform previous fiscal measurements for their job’s sake. If a teacher gets a bad recommendation, why stay in the occupation?

For those who consider education as a lifelong career – it’s about leading young minds to discover the world’s problems and guiding them to become productive and passionate citizens. America’s education system is failing students beyond its minorities. Traditionally speaking, young and inexperienced teachers have always been placed in failing schools, because that’s how they’re molded. Education reform is doing the same thing, but it’s not “doing the same thing over and over,”23 it’s doing the same thing with different historical perspectives, tools, measurements, policies and instruction. There shouldn’t be a divide between traditional and charter school ideologies, best practices should simply be taken from each, and organizations such as “America Forward” that embrace the both worlds of charter and traditional schools are looking beyond all the controversy: because new schooling implementations such as the Extended Learning Time (ELT) and teacher autonomy are extremely effective, when utilized correctly.

The impact of charter schools in New Orleans has been highly scrutinized, and also successful:

“The typical student in a Louisiana charter school gains more learning in a year than his TPS [Tradtional Public School] counterpart, resulting in about two months of additional gains in reading and three months in math. These positive patterns are pronounced in New Orleans and other urban settings where historically student academic performance has been poor. The difference in learning in a New Orleans Charter School equates to four months of additional learning in reading and five more months of learning in math”24

Charter schools are beneficial to America’s educational gaps and inequalities, and traditional schools should collaboratively embrace some of their ideas. The charter school movement will continue to close educational gaps, but also continue to create controversy among policies, communities and districts alike: only to create more gaps that we may not be able to recognize yet. Teachers need to invest far more than two years in teaching to truly make an impact. Canada further expresses the ephemeral uplift of a charter school education, like HCZ:

“In communities like Harlem, people tend to think that a single decent program for poor children is enough to provide escape velocity, to give the children the momentum to orbit around their communities and not be damaged. But they’re wrong. The programs are just not powerful enough. The gravity of the community always pulls the child back down. They might stay in the air for a year, but then lousy schools, lousy communities, the stresses of being poor all begin to weigh on that child and that family, and they begin to fall closer back down to the values and the performance levels of the community.”25

The gravity of these communities not only causes its students to stay in the air for a year, but teachers as well. I believe the power Canada is probing at may rest within federal hands received by educational professionals who know America’s education system best: because as curriculum and knowledge evolves in America, so do the demands of a teacher.

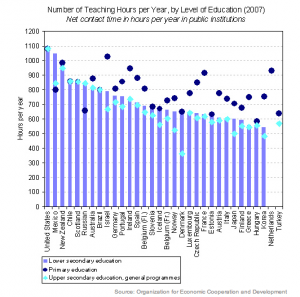

The bottom line is that, America needs to put more value on the occupation of the teacher, and charter schools are harming the appeal of becoming an educator by providing our country’s teachers with little pay and longer hours. Charter schools are bridging gaps in America’s education, but is it possible they’re creating gaps between teachers and their ability or desire to teach? Based the: “World Top 20 Education Poll,”26 in comparison to the leading countries in education such as, “Japan, South Korea and the United Kingdom: the United States ranks 18,” even though, American teachers spend more time teaching than any other country. In 2007, when America’s teaching salaries peaked, teachers spent “on average 1,080 hours teaching each year. Across the O.E.C.D. [The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development], the average is 794 hours on primary education, 709 hours on lower secondary education, and 653 hours on upper secondary education general programs:

American teachers’ pay is more middling. The average public primary-school teacher who has worked 15 years and has received the minimum amount of training, for example, earns $43,633”:27

Until the United States starts to appreciate their teachers as much as they’re valued in countries with exceptional education systems, controversies will continue over accountability or autonomy. I believe Holly Welham points out some of the key international differences among the treatment of teachers in her article: “How Teachers are Rated in 21 Countries Around the World.”28 If charter schools continue to degenerate the value of teachers, there could turnout to be a shortage of teachers in America’s future. Classroom efficiency and technology will evolve, curriculum will evolve with history, but the student only evolves through their teacher. “The new standards won’t revolutionize education. It’s not enough to set goals; you have to figure out how to meet them.”29 Failing education could benefit from the expertise and experience of educators that only higher education attracts in order to truly affect change in America’s education; because if education inequalities began with untrained or inexperienced educators teaching in low-performing schools with low-wages, I believe Einstein when he said: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

Works Cited

“American Teacher (2011).” N.p., n.d. Web. 2014.

“The Lottery (2010).” N.p., n.d. Web. 2014.

Armario, Christine. “Teach For America Met With Big Questions In Face Of Expansion.” TheHuffingtonPost.com. The Huffington Post, 27 Nov. 2011. Web. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/11/27/teach-for-america-met-wit_n_1114995.html>.

Brooks, David. “When the Circus Descends.” Nytimes.com. The New York Times, 17 Apr. 2014. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/18/opinion/brooks-when-the-circus-descends.html?partner=rssnyt&emc=rss&_r=0>.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Employment and Wages – May 2013.” Occupational Employment and Wages. Bureau of Labor Statistics: U.S. Department of Labor, May 2013. Web. <http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ocwage.pdf>.

Center on Reinventing Public Education. “Teacher Attrition in Charter vs. District Schools.” Crpe.org. Center on Reinventing Public Education, Aug. 2010. Web. <http://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/brief_ics_Attrition_Aug10_0.pdf>

Charter School Jobs. “About Charter Schools.” Charterschooljobs.com. K12connect, Inc., 2014. Web. <http://www.charterschooljobs.com/AboutCharters.aspx>.

Christensen, Linda, and Stan Karp. “Why Is School Reform So Hard? The Dual Character of Schooling Invariably Generates Contradictory Impulses When It Come to Reform.” Edweek.org. Education Week, 8 Oct. 2003. Web. <http%3A%2F%2Fwww.edweek.org%2Few%2Farticles%2F2003%2F10%2F08%2F06karp.h23.html>.

Credo. “Charter School Performance in Louisiana.” Credo.stanford.edu. Center for Research on Education Outcomes. 8 Aug. 2013. Web. <https://credo.stanford.edu/documents/la_report_2013_7_26_2013_final.pdf>

Donaldson, Morgaen L., and Susan M. Johnson. “TFA Teachers: How Long Do They Teach? Why Do They Leave?” Edweek.org. Education Week., 4 Oct. 2011. Web. <http%3A%2F%2Fwww.edweek.org%2Few%2Farticles%2F2011%2F10%2F04%2Fkappan_donaldson.html>.

Editorial Projects in Education Research Center. (2011, May 25). Issues A-Z: Charter Schools. Education Week.org. May 25, 2011. Web. http://www.edweek.org/ew/issues/charter-schools/

Einstein, Albert. Ed. Clark, Ronald W., Einstein: The Life and Times. New York: World Pub. Co., 1971. Web.

Hess, Alexander E.M., and Thomas C. Frohlich. “10 Cities Where Violent Crime Is Soaring.” Time.com. Time, 21 Apr. 2014. Web. <http://time.com/6729/10-cities-where-violent-crime-is-soaring/>.

Hess, Frederick M. “American Enterprise Institute.” Doing the Same Thing Over and Over. Aei.org. AEI Online, 17 Nov. 2010. Web. <http://www.aei.org/article/education/k-12/doing-the-same-thing-over-and-over/>.

Ionata, Catherine M., Rick Bergdahl, Henry Seton, and Daniel Lindley. “The High Turnover at Charter Schools.” Nytimes.com. The New York Times, 29 Aug. 2013. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/30/opinion/the-high-turnover-at-charter-schools.html?_r=0>.

Kolderie, Ted. “Ray Budde and the Origins of the ‘Charter Concept'” Education Evolving. Center for Policy Studies and Hamline University, June 2005. Web. <http://www.educationevolving.org/pdf/Ray-Budde-Origins-Of-Chartering.pdf>.

Lewis, Heather. New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and Its Legacy. New York: Teachers College, 2013. Print.

NEA. “Rankings of the States 2013 and Estimates of School Statistics 2014.” National Education Association. Mar. 2014. Web.

NYCSED. “Charter School Office.” Nysed.gov. About Charter Schools: Laws and Regulations: Article 56. NYSED: PSC, 25 Feb. 2014. Web. <http://www.p12.nysed.gov/psc/article56.html>.

Rampell, Catherine. “Teacher Pay Around the World.” Economix.blogs.nytimes & oecd.org. Nytimes.com. The New York Times, 9 Sept. 2009. Web. <http%3A%2F%2Feconomix.blogs.nytimes.com%2F2009%2F09%2F09%2Fteacher-pay-around-the-world%2F>.

Ravitch, Diane. The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice Are Undermining Education. New York: Basic, 2010. Print.

Ravitch, Diane. The Great School Wars: New York City, 1805-1973; a History of the Public Schools as Battlefield of Social Change. New York: Basic, 1974. Print.

Rich, Motoko. “At Charter Schools, Short Careers by Choice.” Nytimes.com. The New York Times, 26 Aug. 2013. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/27/education/at-charter-schools-short-careers-by-choice.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0>.

Roth, Vanessa. Brian McGinn. American Teacher. Video Documentary. 2011. <http://www.theteachersalaryproject.org/>

Sackler, Madeleine. The Lottery. Video Documentary, 2010. <http://thelotteryfilm.com/>.

Smolover, Deborah. “America Forward.” Americaforward.org. New Profit Inc. and America Forward, 2014. Web. <http://www.americaforward.org>.

Sentencing Project. “The Federal Prison Population: A Statistical Analysis.” Sentencingproject.org. The Sentencing Project Research and Advocacy for Reform, Web. 2004. <http://www.sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_federalprisonpop.pdf>.

Tough, Paul. Whatever It Takes: Geoffrey Canada’s Quest to Change Harlem and America. Boston: Mariner, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. Print.

Walsh, Taylor. “Unlocking the Gates: How and Why Leading Universities Are Opening Up Access to Their Courses. Princeton University Press, 2010. Print.

Welham, Holly. “How Teachers Are Rated in 21 Countries Around the World.” Theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media, 03 Oct. 2013. Web. <http://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/teacher-blog/2013/oct/03/teachers-rated-worldwide-global-survey>.

World Top 20 Education Systems. “World Top 20.” worldtop20.org. NJMED, 2014. Web.

- Sackler, Madeleine. The Lottery. Video Documentary, 2010. ↩

- Ravitch, Diane. The Great School Wars: New York City, 1805-1973; a History of the Public Schools as Battlefield of Social Change. New York: Basic, 25. 1974. Print. ↩

- Editorial Projects in Education Research Center. (2011, May 25). Issues A-Z: Charter Schools. Education Week.org. May 25, 2011. Web. ↩

- Ravitch, Diane. The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice Are Undermining Education. New York: Basic, 2010. Print. ↩

- Kolderie, Ted. “Ray Budde and the Origins of the ‘Charter Concept'”Education Evolving. Center for Policy Studies and Hamline University, 1. June 2005. Web. ↩

- NYCSED. “Charter School Office.” Nysed.gov. About Charter Schools: Laws and Regulations: Article 56. NYSED: PSC, 9. 2006. Web. ↩

- Center on Reinventing Public Education. “Teacher Attrition in Charter vs. District Schools.” Crpe.org. Center on Reinventing Public Education, Aug. 2010. Web. ↩

- Charter School Jobs. “About Charter Schools.” Charterschooljobs.com. K12connect, Inc., 2014. Web. ↩

- NEA. “Rankings of the States 2013 and Estimates of School Statistics 2014.” National Education Association. Mar. 2014. Web. ↩

- Charter School Jobs. “About Charter Schools.” Charterschooljobs.com. K12connect, Inc., 2014. Web. ↩

- Christensen, Linda, and Stan Karp. “Why Is School Reform So Hard? The Dual Character of Schooling Invariably Generates Contradictory Impulses When It Come to Reform.” Edweek.org. Education Week, 8 Oct. 2003. Web. ↩

- Tough, Paul. Whatever It Takes: Geoffrey Canada’s Quest to Change Harlem and America. Boston: Mariner, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 53. 2009. Print. ↩

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Employment and Wages – May 2013.” Occupational Employment and Wages. Bureau of Labor Statistics: U.S. Department of Labor, May 2013. Web. ↩

- Sentencing Project. “The Federal Prison Population: A Statistical Analysis.” Sentencingproject.org. The Sentencing Project Research and Advocacy for Reform, 2004. Web. ↩

- Hess, Alexander E.M., and Thomas C. Frohlich. “10 Cities Where Violent Crime Is Soaring.” Time.com. Time, 21 Apr. 2014. Web. ↩

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Employment and Wages – May 2013.” Occupational Employment and Wages. Bureau of Labor Statistics: U.S. Department of Labor, May 2013. Web. ↩

- Armario, Christine. “Teach For America Met With Big Questions In Face Of Expansion.” TheHuffingtonPost.com. The Huffington Post, 27 Nov. 2011. Web. ↩

- Donaldson, Morgaen L., and Susan M. Johnson. “TFA Teachers: How Long Do They Teach? Why Do They Leave?” Edweek.org. Education Week., 4 Oct. 2011. Web. ↩

- Rich, Motoko. “At Charter Schools, Short Careers by Choice.” Nytimes.com. The New York Times, 26 Aug. 2013. Web. ↩

- Ionata, Catherine M., Rick Bergdahl, Henry Seton, and Daniel Lindley. “The High Turnover at Charter Schools.” Nytimes.com. The New York Times, 29 Aug. 2013. Web. ↩

- Walsh, Taylor. “Unlocking the Gates: How and Why Leading Universities Are Opening Up Access to Their Courses. Princeton University Press, 2010. ↩

- Roth, Vanessa. Brian McGinn. American Teacher. Video Documentary. 2011. ↩

- Hess, Frederick M. “American Enterprise Institute.” Doing the Same Thing Over and Over. Aei.org. AEI Online, 17 Nov. 2010. Web. ↩

- Credo. “Charter School Performance in Louisiana.” Credo.stanford.edu. Center for Research on Education Outcomes. 8 Aug. 2013. Web. ↩

- Tough, Paul. Whatever It Takes: Geoffrey Canada’s Quest to Change Harlem and America. Boston: Mariner, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 232, 2009. Print. ↩

- The World Top 20 Education Poll (WT20EP0), 2014 ↩

- Rampell, Catherine. “Teacher Pay Around the World.” Economix.blogs.nytimes & oecd.org. The New York Times, 9 Sept. 2009. Web. ↩

- Welham, Holly. “How Teachers Are Rated in 21 Countries Around the World.” Theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media, 03 Oct. 2013. Web. ↩

- Brooks, David. “When the Circus Descends.” Nytimes.com. The New York Times, 17 Apr. 2014. Web. ↩

This essay asks how the charter school movement has affected the role of teachers its began in the early 1990s, which is an interesting research question that clearly addresses change over time. But the thesis simply states that charter schools have been “beneficial to (closing the) gaps” in US education while “ultimately harmful” to the teaching profession. A richer thesis would have addressed the *how* portion of the research question more clearly. The introduction raises several related topics: teacher salaries, charter school business models, etc., but it’s hard for the reader to understand the overall argument and how these pieces fit together.

The most interesting use of evidence in the essay was its focus on teacher pay and turnover, with extensive use of a range of source materials. But to persuasively argue your point, the essay needs to compare teacher salary and turnover rates between charter schools and traditional schools. Simply comparing teachers to other higher-paid professions doesn’t support the thesis.

Consider this question: Does the essay pin all of the teaching profession’s problems on charter schools, rather than considering other factors such as public education budgets, teacher preparation programs, and status of the profession? Charter schools only enroll about 5 percent of the student population nationally (or 6 percent in NYC), according to this recent NYT story that may interest you (http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/12/nyregion/charters-public-schools-and-a-chasm-between.html). Clearly, charter schools are a fast-growing sector. But if they were to disappear tomorrow, would all of the problems facing the teaching profession disappear too — or might they still be with us? Overall, an interesting essay that makes me think about the topic in new ways.