Upon first glance, it may be troubling to understand why there is so much debate over Affirmative Action. Why would anyone oppose a system in higher education that furthers the rights of minorities and provides them with greater opportunities in admissions and employment? History has also shown that the government has fought hard for multiple decades to instill these protections in attempts to diversify numerous professional fields. Here it is crucial to realize that multiple factors have changed in the social sphere from when affirmative action first originated, and that opponents of the process believe it to be unconstitutional as it allows race to be factored into such an important decision at their own determinant. For instance, many Asian American students believe that they feel “reverse discrimination” in that they are not allowed into colleges of their choice despite having equal or even better SAT scores, high school GPAs, etc. than their counterparts. This essay explores how Affirmative Action has been defined under the equal protection clause over the past few decades, and the debate over it’s feasibility and application in higher education admissions.

Affirmative Action originated after the era of civil rights, as proponents thought of it as a way that employment and admission into higher education could be made more available to minority groups. As President Johnson would state, Affirmative Action was a means to even the starting line of a race for all races. By 2003 this had changed as both opponents of Affirmative Action and the Supreme Court declared that using a quota system to allow greater opportunity for minority groups violated the Equal Protection Clause of The Constitution. However, it was also ruled that race could still be used for diversification purposes if it was used as part of holistically judging an applicant. As such, proponents at the time continued to argue that Affirmative Action was being used to diversify professional and academic fields. Today, opponents of Affirmative Action at Harvard claim that the admissions office has a hidden quota system where points and percentages are used to quantify race in the applications process, a practice that violates the Equal Protection Clause. Proponents have stated that without Affirmative Action, the racial diversity of such institutions would greatly diminish and lead to lack of diversity in thought.

These changes have occurred as a result of a changing social sphere in America, and our desire to provide equality to those who have previously had opportunities deprived of them. However, in doing so, people have questioned whether the government is adhering to the equal protection clause if they are providing extra help or assistance to one racial group over another. The fact that the constitution is also a living, breathing document that is open to interpretation has also fueled debate over how the clause applies to education. Ultimately, the question has become whether America is adhering to it’s democratic ideals if it is diversifying education at the sake of equal treatment to all races. Additionally, ongoing debates have questioned whether it’s even feasible for race to even be considered a part of the admission process, when it’s not a characteristic that one can change or improve as they can their qualifications.

In order to understand the debate over Affirmative Action, it is first important to understand how the term was initially defined in the 1960s-1970s. Affirmative action was seen as a product of the era of civil rights, a time where protests and riots all wished for equal rights to rightfully be extended to African Americans. However, in order to ensure equal rights to African Americans, it was also true that reperations would have to be made for the external and internal pressures that had previously allowed for the subjection of these individuals. President Johnson implicitly brought up this notion of Affirmative Action in his commencement speech at Howard University.

“You do not take a person who, for years, had been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and they say, ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair…it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity.” (Johnson, 1965)

As such, it was understood that additional assistance from the government would be needed as a means to ensure that people of the minority would have equal rights to their white counterparts. Johnson’s ideas were translated into the signing of Executive Order 11246, “which reaffirmed the government’s commitment to promoting ‘equal employment opportunity’ in companies holding federal contracts” (Kotlowski, 1988). Although this was a step in the right direction, no real specific plans for the future were made to reinforce these ideas and the executive order. Additionally, it was questionable whether this change was enough to make sure that individuals in the minority and White Americans were at the same “starting line of the race”.

Johnson’s speech was part of the first of two distinct stages in which Affirmative Action developed. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were also two important events that defined the first stage (Graham, 1992). These two events can be seen as eliminating the pressures that existed in continuing the subjection and discrimination of minority groups. These ideologies transferred into the realm of higher education admissions, as the Civil Rights Act in particular would make “it illegal to discriminate against students and college applicants on the basis of race or gender” (Education.Findlaw, 1964). In understanding the historical context of this time, the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke court case is also vital. The plaintiff in the case, a thirty-five year old white male, was denied application twice from the University of California Medical School at Davis despite his qualifications being higher than those of certain admitted minority students. These students were actually part of the college’s pre-set number of qualified minorities to be admitted (Oyez,1979). Ultimately, five out of the nine justices contended that the use of a “racial quota system…violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964”, however stated that race could be used as part of the college admissions process for the bonafide purpose of diversifying the student body. (Oyez,1979). As such, race could be used in admissions if it wasn’t explicitly discriminating against other races. By having a certain number of seats saved for a certain minority group, it would however, be discriminating against the majority and be considered unconstitutional.

The second stage occurred about a year later, and was said to have introduced new policies/procedures that would bring minority groups up to the starting line. Additionally, emphasis was placed on the role of the presidency and Congress in interpreting a “race-blind Constitution” (Graham, 1992). Important changes included the creation of the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC) in 1965, Title IX in 1972, and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance in 1977 (Graham, 1992 & Mansky, 2016). All three of these changes showed how the government was shifting toward creating an environment in which qualifications, rather than race, were of consideration in employment. Despite the fact that none of these changes directly affected education, they did suggest a “race blind” system that believed providing additional help to one racial group over another was not the goal. Regardless, these events still functioned in allowing minority groups greater opportunity in employment at the time.

The University of Michigan cases, both of which occurred a few decades later in 2003, were crucial in further defining what exactly the Bakke case meant by allowing race to be considered part of the admissions process but not allowing a quota. The first of the two cases in Michigan was Grutter v. Bollinger. In this court case a highly achieving white female was denied admission to University of Michigan’s Law School that was known to “use race as a factor in making admissions decision because it serves a ‘compelling interest in achieving diversity among its student body’” (Oyez, 2003). In order to do so, the committee used “a point system in which students were awarded an additional 20 points for being a member of an underrepresented minority…” (Oyez, 2003). The admissions committee also evaluated the student’s high school GPA, extracurricular abilities, and alumni relationships to determine her eligibility. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor concluded “that the Equal Protection Clause does not prohibit the Law School’s narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions…” (Oyez, 2003). The court reasoned that because admission is decided on a case by case overview of the students’ merits, and race is only one of the factor that is used in holistically obtaining an image of the application, it is not unconstitutional in its use. However, on the same day in the Gratz v. Bollinger court case, the opposite decision was made. The University of Michigan’s Law School was found to violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because they held a certain number of seats for minority students and used the point system.

Subsequently, proponents in the Michigan cases and the Bakke court case, believed that holding seats and allowing extra points for minority students allowed them an advantage that was equivalent to those that majority groups already enjoyed due to their race. Conversely, opponents of affirmative action, did not believe that the law school’s desire to diversify their student body was more important that selectively providing certain races a significant advantage. Once again, the quota system could be compared to something like the literacy tests that were required of certain African Americans to vote prior to 1965. Affirmative Action was viewed as system that would discriminate against a racial group or even allow their race from admissions, regardless of the fact that they were part of the majority.

Conversation had changed in the past decade from whether race can or can’t be allowed as part of admissions, to whether race is being applied constitutionally and without a quota-system. Recent court cases, including the Fisher v. University of Texas, have called under fire whether schools are secretly using a quota-system. A vital court case, with deliberation that is currently occuring, is the Harvard Affirmative Action Case that began around 2012.

The plaintiffs in the case claimed that their child had not been accepted to Harvard because of his ethnicity. “Specifically, they allege that Harvard set a limit on the number of Asian American students admitted to the University and applied a higher standard to their son’s application that it did to applications submitted by White Americans”(Quay, 1999-2019). Harvard immediately denied these accusations and stated that they did not use any quota-system, “to exclude or to include”, nor did they hold Asian Americans to a different standard than White Americans (Quay, 1999-2019). According to the constitution, admissions committees are allowed to use race in their admissions process if it is part of holistically judging an applicant rather than on a quota system where student are awarded points for being one race over another. As such, the admissions committee posited that despite the child being well rounded and having grades that would allow him to succeed at Harvard, other applicants had stronger qualifications. The plaintiff’s family was not satisfied with this response, and an investigation was opened.

In letters between Harvard’s Attorney and an individual at the Office for Civil Rights, a multitude of documents in regard to Harvard’s admissions process were included. Additionally, the process that the committee uses to decide whether an applicant is eligible was clearly stated in the letters and is as follows. All applications are first rated on a scale from 1-4 on academic achievement, extracurricular activities, athletics, and personal qualities. Applications are reviewed by “docketts” that are essentially “sub committees formed around geographical areas” (Quay, 1999-2019). The dockett for Southern California has an acceptance rate of 5.1%, in which Asian Americans have an acceptance rate of 5.6% and White Americans have an acceptance rate of 5.1%. Prior to the court case, The United States Department of Education had also stated that although “Asian American applicants have been admitted at a significantly lower rate than white applicants…this disparity is not the result of discriminatory policies or procedures” (Quay, 1999-2019).

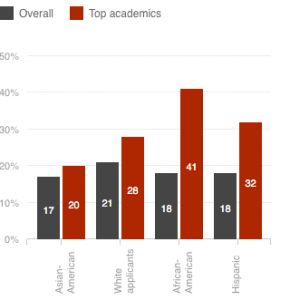

Opponents of Affirmative Action point to the fact that although Harvard denies claims of discriminating against Asian American applicants, they also contend that if they were “forced to abide by racial neutral criteria, the number of black and Hispanic students on campus would plummet” (Biskupic, 2018). As such, opponents focus on the fact that Harvard is admitting to not using a “racial neutral” system for admissions. They pose the question of whether involving race in the process is feasible at all, if the ultimate effect is providing significant advantages or disadvantages to either race. Allowing admissions to one race and baring it for another. Additionally, it isn’t a criteria that applicants can somehow change or improve like they can other criteria. Opponents, including the Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), also point to the fact that the average class of 1600 freshman have consistently been about 23% Asian American, 15% African American, 12% Latino, and 50% White American. SFFA argues that “Asian American applicants are essentially capped below the acceptance percentage”, and that Harvard consistently having these same percentages is proof of use of a hidden quota. (Biskupic, 2018) Critics of the SFFA may argue that if an equivalent number of Asian Americans are applying to Harvard over the years, it is reasonable for the percent of admitted student to remain equivalent. However, a study on the number of applicants, has shown that the number of Asian American applicants has actually grown by nearly 93.7% since 2000 (Avi-Yonah & McCafferty, 2018). As such, to accommodate for a greater number of applicants, we would expect an equivalent increase in acceptance rate. Lastly, opponents of Affirmative Action state that Harvard is able to indirectly use race in a quota-type system by providing Asian Americans with lower “personal ratings” despite the fact that these applicants perform better in academic and extracurricular activities than their non-Asian American peers (Reilly, 2018). Figure 1 shows the “percentage of Harvard Applicants Who Received High Personal Ratings” (Jung, 2018), in comparison to other races.

Figure 1: Personal Ratings

In a rally the day prior to the court cases, the leader of the SFFA attempted to sway public opinion by stating how unethical and unjust it was in “a multi-racial, multi-ethnic nation like ours, [for] the admissions’ bar [to] be raised for some races, and lowered for others” (Reilly, 2018). The question is of whether it would be more reasonable to completely remove race from the admissions process and instead focus on the students’ merits, thus creating a truly “race-blind” system. The argument being made here is that the equal protection clause is not being applied to the racial majority and that enough time has passed from prior subjectation/discrimination for the government to not have to provide significant advantage to minorities.

Conversely, proponents of Affirmative Action mainly argue that removing the policies in place will harm minority groups to quite some extent. Subsequently, there will be a notable decline in diversity among races, and diversity of thought on college campus as racial inequality deepens. We can also expect for future opportunities for minorities to decline if they are allowed access to higher education at lower percentages. Ultimately, proponents of Affirmative Action view allowing race as part of the decision as a way to even the playing field for minority students, and allowing them the same benefits that their non-minority counterparts can afford. They argue that the diversification of education and employment is feasible and protected under the equal protection clause.

Clearly both proponents and opponents in this case are making very emotionally charged arguments, which doubled with the racial climate, will make it difficult to arrive at a decision in the next few months. Additionally, the decision made in this court case will set precedent as to how race is considered in education and employment in the future. Ultimately, this court case highlights how the definition of Affirmative Action have changed significantly since its origin and shows how application of the equal protection clause to education has changed significantly over the past few decades. Despite all the time that has passed, the question remains whether race should even be allowed as part of the admissions process and whether we can sacrifice equal treatment of all races for the purposes of diversifying the student body at colleges.

References

Affirmative Action and College Admissions. (1964). Retrieved from https://education.findlaw.com/higher-education/affirmative-action-and-college-admissions.html

Avi-Yonah, S. S., & McCafferty, M. C. (2018, October 19). The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved May 1, 2019, from https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/10/19/acceptance-rates-by-race/

Biskupic, J. (2018). Harvard affirmative action trail arguments come to a close. CNN Politics. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/03/politics/harvard-trial-wrap/index.html

Graham, H. (1992). The Origins of Affirmative Action: Civil Rights and the Regulatory State. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 523, 50-62. Retrieved from: www.jstor.org/stable/1047580.

Gratz v. Bollinger. (2003). Oyez. Retrieved April 2, 2019, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2002/02-516

Grutter v. Bollinger. (2003). Oyez. Retrieved April 2, 2019, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2002/02-241

Johnson, L. B. (1965, June 4). Commencement Address at Howard University: “To Fulfill These Rights”. Retrieved May 1, 2019, from https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/commencement-address-at-howard-university-to-fulfill-these-rights/

Jung, C. (2018, November 02). Harvard Discrimination Trial Ends, But Lawsuit Is Far From Over. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/11/02/660734399/harvard-discrimination-trial-is-ending-but-lawsuit-is-far-from-over

Kotlowski, D. (1998). Richard Nixon and the Origins of Affirmative Action. Historian, 60, 523-541. Retrieved from: www.jstor.org/stable/24451639

Mansky, J. (2016, June 22). The Origins of the Term “Affirmative Action”. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/learn-origins-term-affirmative-action-180959531/

Quay, H. (2012, February 2). Letter to Nicole Merhill, Office for Civil Rights. Retrieved from https://apps.washingtonpost.com/g/documents/local/evidence-in-harvard-admissions-trial/3248/ Cited in Evidence in Harvard Admissions Trial, The Washington Post, 1999-2019

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. (1979). Oyez. Retrieved April 2, 2019, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/1979/76-811

Reilly, K. (2018). As the Harvard Admissions Case Nears a Decision, Hear from 2 Asian-American Students on Opposite Sides. TIME. Retrieved from http://time.com/5425147/harvard-affirmative-action-trial-asian-american-students