In 1972 Title IX was passed, which is a portion of the Education Amendments of 1972 stating “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance…” (OASAM). Although this portion of the Education Amendments was not specifically aimed at fixing discrimination in athletics, Title IX became most known for and had one of the greatest effects on ending sexist inequity in sports. In fact, the words “athletics” or “sports” were not even mentioned in this section of the amendment, which beckons the questions, when Title IX was originally debated among policymakers, how much was the focus on academics versus athletics? To what extent has this balance shifted over time, and what were its consequences?

Title IX originally came to passage in order to specifically battle gender inequity and discrimination in education. Those who advocated the enactment of Title IX spotlighted sex discrimination issues in education and the workplace such as equal pay, sex bias in school texts, and tenure track opportunities. However, women’s athletics quickly became one of the most hotly debated topics of the 1970s and 80s shortly after the passing of Title IX. Currently, Title IX is practically synonymous with women’s athletics. Over time, the focus of Title IX shifted from gender inequity in education to gender inequity in sport, launching a revolution in women’s athletics.

Although Title IX is widely known as a catalyst for advancements in women’s sports, the focus on athletics was unintended. Initially, its supporters focused on the demand for gender equality in education and the workplace, with no real thought put into the question of athletics. The impetus behind Title IX was the prevalent discrimination women faced in all aspects of the educational experience, including students, administrators, and professors. The law was purposely designed to specifically cover the banning of sex discrimination within educational institutions because previous laws like Title VII and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not apply to education but instead focused solely on discrimination in employment (Ware, 3). These issues were discussed without mention of athletics during a 1970 hearing in the House of Representatives before the Special Subcommittee on Education on discrimination against women:

prohibit[ing] discrimination against women in federally assisted programs and in employment in education; to extend the equal pay act so as to prohibit discrimination in administrative, professional and executive employment; and to extend the jurisdiction of the U.S. Commission of civil rights to include sex. (Congress)

During these hearings and debates about the law, athletics had barely been mentioned, and Representative Edith Green of Oregon predicted in 1971 that Title IX would “probably be the most revolutionary thing in higher education in the 1970s” (Ware, 4). Another female Representative, Patsy Mink of Hawaii, stated in hindsight, “When it was proposed, we had no idea that its most visible impact would be in athletics. I had been paying attention to the academic issue. I had been excluded from medical school because I was female” (Ware, 4). No one involved in the legislation and passing of Title IX could have foreseen the enormous splash it would make in the future of women’s sports. However, almost immediately after the passing of Title IX in 1972, the switch in focus on athletics occurred for several reasons.

The idea of gender equity in athletics was originally not considered during debates leading up to the passing of Title IX because athletic programs themselves did not receive federal funding, so this issue was not seen as a likely target for enforcement. However, since the law applied to the entirety of an institution receiving federal funds, not just a specific program, athletics fell under its jurisdiction and therefore needed to be addressed (Ware, 4). College athletic administrators, coaches, and directors began to realize the potential enormity this legislation could have on athletics, and soon enough many ordinary Americans also began questioning the obvious gender inequity in the field of sports. The social context of the time was also crucial to the shift in thinking about women’s participation in athletics. The Women’s Liberation Movement was at its peak, and female athletes were becoming increasingly visible in the public sphere. Billie Jean King, a tennis icon who famously beat Bobby Riggs in a battle of the sexes tennis match, testified in congressional hearings in 1973 and became the first female athlete to ever win $100,000 in one year (Ross Edwards). In the late 1960s, a female ran the Boston Marathon for the first time. These public acts helped inspire the argument for gender equality in athletics.

The shift from gender equity in education to athletics was also spurred by the visibility of sex discrimination in sports. The widespread feminism of the 1960s had a great impact on equalizing athletics because for the first time, it opened the nation’s eyes to the disparities between men’s and women’s opportunities. The sex segregation in athletics was much easier to see after the nation’s consciousness was raised by modern feminism (Ware, 2). Margot Polivy, an attorney for the American Intercollegiate Athletic Association for Women (AIAW), argued that inequality was easier to explain and understand through sport than through everyday sex role stereotyping and discrimination (Ross Edwards). Some modes of discrimination are “subtle, almost invisible- not that in athletics” (Ware, 2). Generally speaking, the policymakers and officials in D.C. were not the original ones pushing for more attention on women’s athletics, it was a movement from the bottom up where women’s groups and common Americans were fighting from the athletic standpoint. For example, there was a series of court cases brought by fathers of athletically gifted daughters in the early 1970s (Ross Edwards). However, not all men were as inclined to extend equality to women in sports as these eager fathers.

Ironically, the opponents of Title IX, mostly men, actually drew positive attention to the fight for equity in athletics through their lobbying against it. The supporters of Title IX targeted athletics as a direct result of all the attention opponents brought to the issue. For instance, men’s opposition caused women in AIAW to take a strong position in favor of the regulations regarding athletics sooner than they otherwise might have (Ross Edwards). Many female athletic administrators, some of whom were originally ambivalent towards the law, began to sense its power when they saw how angry it made men (Ware, 13). The NCAA was one of the greatest original opponents of the law, and they took a strong stance against holding collegiate championships for women. However, after they saw all the attention and progress women’s athletics had made in such a short period of time, NCAA officials decided to accept the idea of women’s sports, not out of an honest desire for equity, but because they sought profit.

The booming focus on gender equity in athletics had great success in the 1970s. As journalist Candace Lyle Hogan observed at the time, “Fueled by an almost chemical interaction of a federal anti-sex discrimination law, the women’s liberation movement, and what is called the temper of the times, women’s sports took off like a rocket in 1972” (Ware, 7). The number of women’s teams at both the high school and college levels dramatically raised, reaching a 66 percent increase in women’s college teams by 1999 (Simon, 4). From 1971 to 2002, there was an 847 percent increase in high school female athletes, from 294,015 participants to a whopping 2.7 million participants (Simon, 4). The period from 1972 to 1981 witnessed the greatest growth in women’s participation and the amount of money spent on female athletic programs, but this is also relative to the extremely poor state women’s athletics was in before. Any amount of progress feels like leaps and bounds when starting from practically nothing. This growth, however, did not continue throughout the 1980s, and many aspects of women’s athletics saw substantial setbacks during this time period.

The 1980s is considered a stalemate in the advancement of women’s athletics for several reasons. By 1981-1982, the AIAW, which prided itself in focusing on the “student” aspect of student-athletes, had collapsed and the NCAA had taken over women’s collegiate sports. As author Susan Ware wrote of this turnover, “A significant chance for a different kind of women’s athletics- less commercial, more focused on education and participation, potentially less exploitative- had been lost” (Ware, 12). Because men were accepting the new changes in athletics, they started to take advantage of the new opportunities in employment. For instance, because of Title IX, jobs coaching women’s teams became better compensated and therefore more attractive to men, and the gap between men’s and women’s coaching salaries since the 1970s has actually widened (Ware, 15). Additionally, most institutions merged their previously segregated athletic departments, naturally resulting with men in charge of administrative positions in athletic departments. Women had coached 92 percent of women’s teams in 1973, but by 1984 this had dropped to 53.8 percent and in 2002 it was only 44 percent (Ware, 15). Title IX inadvertently resulted in reverse effects on employment opportunities in athletics for women during the 1980s, and female student athletes similarly suffered.

Politics had a significant influence in the backsliding of progression in women’s sports in the 80s. Not only did the Equal Rights Amendment fail in 1982, but also the Republican takeover of presidency of 1981 proved detrimental to the civil rights cause, as Ronald Reagan attempted to scale back big government and limit federal initiatives (Ware, 14). In specific, one court case in 1984 had the most damaging affect in enforcing Title IX. The Grove City Supreme Court decision held that only particular college departments that received federal funds directly were subject to Title IX; therefore, if a department did not receive direct federal funding they could dismiss the ideals of Title IX (Simon, 71). The New York Times called this a pure example of “judicial activism”, and it resulted in schools cutting recently added women’s teams and scholarships, and the Office for Civil Rights cancelled twenty-three investigations (Ware, 14). This stalemate continued until 1988 when the Civil Rights Restoration Act was passed in Congress over Reagan’s veto, which restored the broad coverage of Title IX (Ware, 15). This brought the future of women’s athletics back on track, but in the years to come, more consequences ensued.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, a significant problem emerged that has yet to fully disappear. Many schools were still following the methods they adopted in the 70s, which dealt with Title IX by linking participation opportunities to the proportions of male and female enrollments. In an attempt to end sex discrimination in education, many schools were admitting significantly more women than men. In the fall of 1998, women comprised 59 percent of the student body at Providence College (Hogshead-Makar, 198). This situation was extremely common in schools, and by 2000, 57 percent of all bachelor’s degrees were earned by women (Simon, 4). Although this was a tremendous success for women, it conflicted the original intentions of Title IX because now the scales were unfairly tilting in the opposite direction. For example, to keep up with schools’ enrollment proportion policies, more and more women’s teams were being added to collegiate athletic programs. Since most schools had tight budgets, many programs cut men’s “minor” sports teams, like gymnastics and wrestling, in order to fund these new women’s teams (Simon, 72). Many men and women alike viewed this as reverse discrimination and intolerable. One lawyer who studied the effects of Title IX called this elimination of men’s non-revenue sports “the least fair and least educationally sound means of resolving the dilemma of Title IX compliance” (Ware, 17). This debate over funding between men’s and women’s sports continues in schools across the nation and although the practice of cutting men’s sports has somewhat diminished, it has not fully disappeared.

While athletics has historically been focused on in discussions of Title IX, advancements in gender equity in education have also had a significant impact on the learning experiences of women as well as on the subsequent job opportunities. The debate of women’s athletics has seemed to overshadow the progressions made in educational experiences of women because of the popularity of the topic of athletics and its enormous strides made in such a short time. While the issues in women’s athletics stole the spotlight over the years following Title IX, the quest for gender equity in education and employment in education was always continuously under way and advancing- it was just more behind-the-scenes. As Nancy Hogshead-Makar, law professor at Florida Coastal School of Law and 1984 Olympic gold-medalist, noted, “Title IX is working every bit as hard in the classroom as it is on the athletic field” (Kilman). Since its enactment in 1972, Title IX has worked to lawfully end sex discrimination in schools by requiring safe and accessible learning environments for both sexes, guaranteeing pregnant and parenting students equal opportunities, and requiring that course offerings and career counseling not be limited by gender (Kilman). Students are also protected against sexual harassment by faculty members as well as against gender bias in standardized testing, textbooks, and in the use of technology.

Title IX and the fight for gender equity in education has seen much success, as well as many drawbacks. Early advances were made between 1970-1975, when about 150 women’s studies programs were established across the country for the first time (Hanson, 85). In addition to the high rates of bachelor’s degrees earned by women, today women make up 58 percent of graduate students and more than half of all medical and law students are women (Hanson, 83). By 2004, women composed almost one half of all the teachers in two- and four-year colleges (Hanson, 83). One of the most powerful examples of changes after Title IX is the amount of women in math and science courses, earning degrees in these subjects in record numbers. In the mid-eighties, women earned a high of 36 percent of computer science degrees, and in 2005, women earned slightly over half of the doctorates in life sciences (Hanson, 84-85).

However, many aspects of education were negatively affected by the intense focus on sports. For instance, recruited athletes are given special advantages in admissions despite low SAT scores, and their education is not a priority. As the Carnegie Commission Report investigating intercollegiate athletics stated, “The defects of American college athletics are two: commercialism, and a negligent attitude toward the educational opportunity for which college exists” (Ware, 26). This statement reigns true today, where oftentimes the opposite effect that Title IX had intended occurs with students’ ignorance towards education and excessive focus on sports. In academics, people first blame a female student’s lack of success on her gender, race, or family income. In sports, the female athletes themselves aren’t to blame for the failure of the system to provide them with opportunities- the answer is to change the system. This answer should also be applied to education. High school and collegiate athletes are called “student-athletes” for a reason, where “student” takes precedence. However, nowadays this is often not the case.

Although the focus of Title IX has been predominantly on the discussion of athletics, the fight for gender equity is just as if not more important. Originally, the discussions of the legislation targeted educational opportunities and working to end sex discrimination in educational employment. Despite the successes seen in education, especially higher education, for women, the successes seen in women’s athletics has seemed to overpower those advancements over the years when evaluating the effects of Title IX. Today, women are excelling in every realm of athletics and education as a direct result of Title IX. Although the focus of debate between education and athletics has shifted over the years, both venues are extremely important in the overall end to sex discrimination in the United States. Full gender equity in education and athletics has not yet been met, but by measuring the progress seen thus far, equity is surely in the near future.

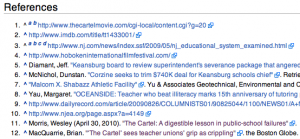

Works Cited

Congress, House, Committee on Education and Labor, Discrimination Against Women: Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on Education, 91st Cong., 2nd sess., 17 June 1970

Hanson, Katherine, Vivian Guilfoy, and Sarita Pillai. More than Title IX: How Equity in Education Has Shaped the Nation. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009.

Hogshead-Makar, Nancy, and Andrew S. Zimbalist. Equal Play: Title IX and Social Change. Philadelphia, PA: Temple UP, 2007.

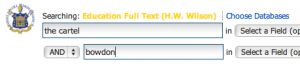

Kilman, Carrie. “Beyond the Playing Field.” Teaching Tolerance no. 42 (Fall2012 2012): 29-33. Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost

Pauline, Gina. “Celebrating 40 Years of Title IX: How Far Have We Really Come?” JOPERD–The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 83.8 (2012) Questia.

Ross Edwards, Amanda. “Why Sport? The Development of Sport as a Policy Issue in Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972.” Journal of Policy History 22.3 (2010) Project Muse

Simon, Rita J. Sporting Equality: Title IX Thirty Years Later. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2005.

Ware, Susan. Title IX: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2007.