Women, commonly seen as the symbol of “nurturing”, are believed as the perfect choice for teaching. In the United States, when women first entered the teaching field, they were told to think of this job as a noble mission; they were sent to save the poor children (Goldstein, 2015). But unlike male teachers, without access to higher education, these women were unable to teach students properly. This resulted in low payment for female teachers and the stereotype that women were not good at teaching, but rather caring for children. However, WWII became a watershed moment for women to access higher education due to economic needs and new societal attitudes (Glazer-Raymo, 1999). After the mid 1960s and early 70s, many colleges in the US began to co-educate women and men. Women were able to access higher education and enter academic fields, and U.S. colleges and universities began to hire more female faculty during the 1970s and ’80s. However, many female faculty used to describe their experiences on and off campus as “inadequate”, “uncomfortable”, “an impostor” and “muted” (Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). How have female faculty experiences changed over time both on and off campus at colleges across the United States, from the 1970s and 80s to today?

Overall, the status of female faculty has been positively uplifted, but there are many obstacles. Regarding female faculty’s working environment on campus, female faculty used to being seen as incapable of teaching and unprofessional; today, there are women in every field, including female faculty, that are still being marginalized. Female faculty earn less than their male colleagues in the past, and still do despite efforts to reduce differentiation. Off campus, female faculty do not receive proper welfare and care in the past and today. Thus, I will examine the changes mainly in the professional field, salary, and welfare. By look at the female faculty experience over time, such as the difficulties they face in their working environment, we can understand the needs of female faculty members, and what has been done and what needs to be done in order to improve the female faculty working environment.

First, I will examine female faculty’s working environment on campus. Although women were able to receive higher education, female faculty were still struggling to teach when they entered universities and colleges. Many of them felt depressed for not knowing how to teach. Not all new professors struggle with such problems, at least not all male professors. Unlike their female colleagues, male professors were able to receive the guidance of the “game” from their mentors. Because of the lack of general career instructions, female faculty became unaware of important steps to achievement. The lack of professional guidance and support not only caused female faculty to struggle with their work, but also made their male colleagues label them as “naive” and “soft”(Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). With such labels, female faculty were then limited in the field. First, female faculty often received rejections of their professional work. In the book Women of Academy, author Aisenberg and Harrington described a story a female Arabic scholar who was unable to publish her work due to her gender. She then “took it home… never submitted the manuscript again to anybody, never looked at it, never did anything and that was the end of it”(Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). Such frustration then created a vicious circle; female faculty were seen as amateurs, and therefore had fewer opportunities to publish their work. This vicious cycle offered an excuse for the universities and colleges to give less tenure track position to female faculty, instead they were often assistant or associate professors (Glazer-Raymo, 1999).

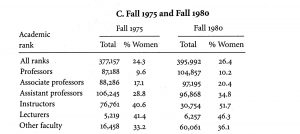

The data suggested that female faculty were being despised. From 1970 to 1993, the percentage of female faculty in universities and colleges has grown from 24.3% to 51.7% (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics). Although there was growth towards an equal number of faculty

(the percentage of full professor has only changed from 9.6 to 17.2), many female faculty were still staying as associate and assistant professors, instructors, and lecturers (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics). Less than two-fifths of female faculty were on the tenure track (Gerald & Hussar, 1995). Data suggests that during 2016, the percentage of female faculty had increased up to 45, which 32% were professors, 45% were associate professors, and 51% were out of tenure track (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics). This gap is gradually closing, but with most female faculty still stay in the lower end position.

Another limitation in the professional field for female faculty was the label of “softness” created the stereotype that female faculty were only capable of “soft” academic subject such as human subjects(Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). The word “soft” was saying “easy” in a nicer way. Though women did tend to study in human subjects such as literature, psychology, and arts, women were entirely capable of studying and teaching “hard” subjects such as math and science. Then the reason many women chose “soft” subjects first was “you’d be doing something else”(Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988), the resistance from the “hard” field that refused to let women entering the field; second, many women chose the “soft” field because these field like arts and literature could provide ways for women who were able to access higher education to share their experience and feelings with other women in order to create changes and provide support (Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). Today, female faculty do have the ability to publish their work and teaching in all kinds of fields. However, there are still discriminations against female faculty in the “hard” fields. It is still difficult for females to enter the STEM areas, although some of them are able to access these programs, they face microaggression and their voices are not being heard. Many of them feel isolated and marginalized (Smith, 2014).

Female faculty also face more pressure than their colleagues from both work and home, and many female faculty feel stressed (Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). Marriage often will put female faculty in a difficult position: they will face the stereotype from school that women spend less energy and time at their career, then categorize them as unnecessary; their students also seen female faculty as moms but not professors (Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). One female professor described her experience after getting pregnant: her school did not expect her to teach. She also said that “whenever anyone spoke to me, they brought up my pregnancy. Nothing else ever seemed to come up”(Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988, p110). School institutions often will make female faculty choose between family and career, for they think that women are not capable of too many responsibilities.

Secondly, I will look at the salary of female faculty members. There was and is no equal pay between male and female professors. When women first entered the teaching field, they treated this job as a noble mission, they were sent to poor places with little and even no money. Many schools administrations then used this idea to pay female teachers less than the male teachers (Goldstein, 2015). This act did not change even after women were professionally trained to be teachers and professors and the federal government’s involvement since the 1960s in employment practice stipulated rules that against sex and race discrimination (Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). Many female faculty argued that they were not only paid unequally compare to their male colleague but also extremely underpaid by universities and colleges. A female part-time university teacher described her feeling: “yet, when I look at the person who sits across the hall from me and makes three times what I make, doing much less work, seeing fewer students, correcting fewer papers…”(Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988 P36). One excuse that the most school institutions used to decrease the female faculty’s salary during the 1970s was the argument that female faculty were not serious about their job. They argued that the female faculty would leave their job after marriage based on the social norm that women needed to take care of the housework. Because of the undercapitalization, some unmarried female faculty needed to work another job in order to make a living. When female faculty did get married later, they would have a lower hourly wage. The reason for the difference again, would be because these female faculty would put more energy on their housework (Glazer-Raymo, 1999).

According to U.S. Department of Education, during 1972 to 1973, female faculty (here female faculty only include professors, associate professors, assistant professors, and instructors) only made 82.7 percent of male faculty’s salary (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics). This disparity was decreasing during the 1970s and 80s, but once again, the salary gap became wider during the 90s. Beginning in 1990, female faculty’s salary had decreased from 90.6% to 79.9%. In 2015, the disparity was 82.5%, not even mentioning the disparities in different academic field and disciplinary. Female faculty tend to earn less money in male-dominated fields like business, education, engineering, and health science (Kopka & Korb, 1996). Female professor only made 69.5% of their male colleagues basic salary and 61.8% of their total income (Glazer-Raymo, 1999). Today, there is salary schedule that requires equal pay for both female and male professors; however, there are 33 states in United States do not have statewide salary schedule (Hopkins, 2018). Also, the salary is different schools by schools. Female faculty often do not have the mobility as male faculty to work in better-paid schools, for female faculty do get tied up with their family choice, like female faculty need to consider the distance between their workplace and their children’s school. So even if equal pay is required, there still is a salary gap between male and female faculty (Hopkins, 2018).

Even with the same amount of salary, female faculty are given more work and responsibility than their male colleagues. Because people still hold the stereotype that nurturing and caring are in women’s nature. Thus, people tend to hold higher expectation for female faculty than male faculty. Students tend to ask female faculty more questions and special favors. One professor mentioned that “students come to my regular office hours to discuss issues specifically related to the course” and “Students send emails asking questions about class materials” (El-Alayli & Hansen-Brown, 2018). Students will also ask for redo assignments for a better grade, stop by offices without appointment, and expect friendly behaviors more from their female professors than male professors (Flaherty, 2018). Female faculty often spend more after school time to help their students. While female faculty are not being paid and rewarded, when male faculty do the same thing, they are being paid. Female faculty do not have equal salary as their male colleagues, but are underpaid for their effort.

Lastly, I will examine the female faculty’s welfare. Female faculty not only make less salary than their male colleague, but have less welfare, for example, the retirement fare. Because retirement fare is linked to salary, thus female faculty often have lower social security and retirement position (Glazer-Raymo, 1999). Second, because of the social norms, some female faculty also carry the responsibility to take care of their children. However, not every college and university provides daycare for faculty’s children which creates distractions for female faculty and make female faculty waste time and energy. Even if there is daycare, the cost is often higher than female faculty’s salary (Glazer-Raymo, 1999).

Female faculty are being held to high standards by their students. “It is more difficult for female professors to meet student expectations, perhaps resulting in poorer course evaluations, and putting more work demands and emotional strain on female professors”(Flaherty, 2018). Female faculty not only have to deal with consequences from their family, but also need to help students to solve their personal issues. Many female faculty also face sexual harassment from their colleagues and students, but many of these cases are not being reported (Glazer-Raymo, 1999). A survey suggested that more than one half female faculty had experienced sexual harassment in 1993 (Stobo, Fried & Stokes, 1993, p. 349). However, there is hardly news and report focus on female faculty member’s experiences. Female faculty often feel stressed, but there is no counseling provided for them (Aisenberg & Harrington, 1988). There is lack of attention about female faculty’s mental health in the past and today.

Compare to the past, today female faculty do have more status. Women are able to enter in all kinds of academic fields, publish their progress, and make more money. However, this does not mean that female faculty are better off. The public seems to forget that female faculty need help too, for female faculty still face gender discrimination which many women are still being rejected from important studies. Because of the stereotype toward women, female faculty have to carry both responsibilities from home and workplace. Especially in the teaching field, the public holds a high expectation for women.

“Women feel better about their work and themselves when they enjoy greater autonomy, more control over their work schedules, reasonable job demands and greater job security, more equal opportunities for advancement, more access to flexible time/ leave benefits and dependent care benefits, more supportive supervisors and a family-friendly workplace culture, and spouse or partners who take more responsibility for family work” (Glazer-Raymo, 1999, p39)

If the public wants female faculty to be the perfect teacher, then we should create a comfortable environment for them to show their talent.

Reference

- Glazer-Raymo, Judith. Shattering the Myths: Women in Academe. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins UP, 1999. Print.

- Aisenberg, Nadya, and Mona Harrington. Women of Academe: Outsiders in the Sacred Grove. Amherst: U of Massachusetts, 1988. Print.

- Hopkins, E. (2018, April 23). Is There a Gender Pay Gap in Education? Retrieved from https://www.weareteachers.com/gender-pay-gap-in-education/

- Goldstein, Dana, author. (2014). The teacher wars: a history of America’s most embattled profession. New York : Doubleday,

- El-Alayli, A., Hansen-Brown, A.A. & Ceynar, M. Sex Roles (2018) 79: 136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0872-6

- Stobo, J. D., Fried, L. P., & Stokes, E. J. (1993). Understanding and eradicating bias against women in medicine. Academic Medicine, 68(5), 349.

- Smith, C. A. S. (2014). Assessing Academic Women’s Sense of Isolation in the STEM Disciplines. In P. J. Gilmer, B. Tansel, & M. Hughes Miller (Eds.), Alliances for advancing academic women: Guidelines for collaboration in STEM fields (pp 97-113). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Chan-Kopka, Teresita L. & Korb, Roslyn A. & Educational Resources Information Center (U.S.). (1996). Women, education and outcomes. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, Educational Resources Information Center: National Center for Education Statistics

- Flaherty, C. (2018, January 10). Study finds female professors experience more work demands and special favor requests, particularly from academically entitled students. Retrieved April 6, 2019, from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/01/10/study-finds-female-professors-experience-more-work-demands-and-special-favor

(Mondale, S., Aronow, V., Backpack Full Of Cash, 7:02)

(Mondale, S., Aronow, V., Backpack Full Of Cash, 7:02)

(Mondale, S., Aronow, V., Backpack Full Of Cash, 49:11)

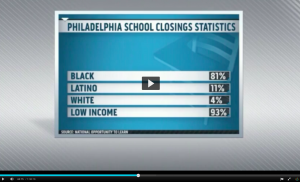

(Mondale, S., Aronow, V., Backpack Full Of Cash, 49:11)