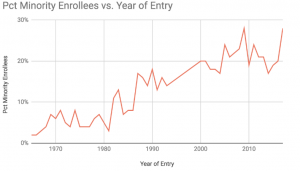

Today when we think of Trinity College, a predominately white institution, we want to also assume that this space is open for students of color. Considering the number of students of color that attended this institution from the 1970s until now the changes are undeniable. There are currently 20% students of color on campus compared to 4% in the late 1960s. That means 1 in 5 students here at Trinity College, is a student who comes from a non-eurocentric background. Diversity, in its many forms, is one of the many selling points for colleges across America, and Trinity has acknowledged it’s important, and in fact, the befits of variety of students to be on their campus. With America’s history with slavery, which has internalized into institutional racism, to this day students of color have a hard time applying and getting accepted into higher education. Even today colleges in America stay predominantly white, even with this newfound urge to admit those who’ve been historically left out of colleges. Students of color often have a hard time considering the possibility of higher education due to financial issues, no exposure to higher education and lack of resources and support for their communities and schools.

This essay explores the history behind some of the policies from Trinity’s end and some national changes that have affected the rate of students of color acceptance to Trinity College. In Trinity’s case, it wasn’t until 1968 that the administration started making the effort in accepting large numbers of African American and other minority students to its campus (History). This push was influenced by some of the political and social factors in America such as the civil rights movement, and especially the death of Dr. King. Trinity guided their students into understanding social structures and the racial tension in America. As a student of color here at Trinity, I know how great of an opportunity it is to be part of such an institution but I can’t help but feel underrepresented not only in classrooms but also in social spaces. Since my arrival at Trinity, I wanted to explore some of the reasons as to why students of color are the slowest growing population at Trinity. This leads to the question: When did Trinity experience the most growth in students of color, and were these periods of growth linked to changes in Trinity programs or national influences?

BACKGROUND

Upon doing research for the acceptance rates for students of color, I was able to find a copy of Trinity College Admissions from 1969-1998 and a factbook of Admission from fall 1999 to spring 2017. Since I had two sets of data, I merged the information to create a line graph that showed the changed over time in Trinity’s Admission for Students of color from 1969-2017. After making the graph, I was able to clearly pinpoint the years where there was a change over time in the acceptance rates for students of color at Trinity. For the purposes of this paper, I will be focusing on some of the forces that promoted the enrollment of students of color at Trinity College, specifically black students.

Trinity’s First Move

In his book Connecticut, Albert Van Dusen detailed everything that ever occurred in Connecticut from 1916 to 1999, including the establishment of Trinity College in 1824 by Bishop Thomas Brownell.  The college first opened as Washington college and from its conception, Washington College was very exclusive, only open to about 9 students. During this time, slavery was still very much legal in the state of Connecticut. However, Trinity was ahead of its time! In 1830, Bishop Brownell awarded Edwards Jones, a black man preparing for his work as a missionary and educator, with a Master of Arts degree. On campus, there was another student of color, the student was reportedly from Africa and attended Trinity College in the early 1830s. The college was then renamed Trinity College in 1845 and with its new name, there was a new location, which consisted of one housing chapel, library, two Greek Revival buildings, and lecture rooms and dorms. In the late 1800s early 1900s, Trinity increase enrolment to 500 students (History). Still, Trinity didn’t maintain any official records on the racial backgrounds of their undergraduate and graduate students, until late in the 1960s.

The college first opened as Washington college and from its conception, Washington College was very exclusive, only open to about 9 students. During this time, slavery was still very much legal in the state of Connecticut. However, Trinity was ahead of its time! In 1830, Bishop Brownell awarded Edwards Jones, a black man preparing for his work as a missionary and educator, with a Master of Arts degree. On campus, there was another student of color, the student was reportedly from Africa and attended Trinity College in the early 1830s. The college was then renamed Trinity College in 1845 and with its new name, there was a new location, which consisted of one housing chapel, library, two Greek Revival buildings, and lecture rooms and dorms. In the late 1800s early 1900s, Trinity increase enrolment to 500 students (History). Still, Trinity didn’t maintain any official records on the racial backgrounds of their undergraduate and graduate students, until late in the 1960s.

Although Trinity did admit a couple of black students since its conception, colleges around the nation were more focused on working towards desegregating their campus. Large colleges such as Dartmouth and Princeton and even smaller ones like Bowdoin and Swarthmore provided black students with scholarship opportunities as well as encouraging their own students to become admission representatives. For schools like Dartmouth, this was one of the many ways that the schools used to get their message to students of color across the nation. In 1964, noticing the lack of black students on their campus, Trinity students took the Trinity Tripod to called out the student body and administration for not following the same suit. The editorial suggested that Trinity should start touring urban high schools as it will encourage marginalized students to consider and even start applying to higher education. One particular reason why there was a rise in enrollments for students of color at Trinity was due to changes from both Trinity’s and National level influence. In response, F. Gardiner Bridge, of admissions, did an interview with the Trinity Tripod to say that Trinity is looking for “the best-qualified candidates we can get, no matter who they are” (Knapp 337). That same year, admission staff visited over 400 high schools in California, Texas, Illinois, Florida, New York, etc, with a focus on inner-city schools in the metropolitan area. Trinity was able to adapt some of the strategies used to attract black students, and they were successful in doing so. According to the Trinity College Admissions Statistics, there was a 2% increase in enrollments of students of color in the years 1965-1966 (Graph) With students going out to public high schools and advocating for Trinity, students of color were presented with this opportunity that higher education is feasible with the support of this institution.

The president at that time, President Albert C. Jacobs, was not only a huge advocate for a liberal arts education but he also emphasized the importance of inclusion at Trinity. In his final public address to the class of 1964, he urged seniors to “to seek out in the community in which you find yourself a young man of the culturally disadvantaged group, a potential candidate who is equipped or who can be helped to equip himself for admission to Trinity or to another college or similar standing” (Knapp 329). He continues to say that we should “encourage him, plant in him the desire for higher education”, which he states is not only for the benefit of the individual but also for Trinity. He expected Trinity to be filled with diverse point of views, where students can reflect on current social issues from different perspectives- which he emphasized is the purpose of a liberal arts education. As the president of the school, he made the first move in trying to encourage Trinity to open its doors to different ideas, and people from different backgrounds.

In the chapter Currents of Change, Peter Knapp covers changes at the national scope from the civil rights movement to the rise of the Black Panthers, undergraduate rebellions on college campuses, and the death of leaders like John F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. being some of the few and how they have affected the Trinity community. Despite the changes around it, Trinity College was ranked first in America’s liberal arts education institutions. However, on April 4, 1968, the assassination of Dr. King’s took Trinity and the rest of the nation by storm. This was an external influence that encouraged President Jacobs to called an emergency meeting with members of the Trinity community, and gave a speech on how Trinity needs to “utilize its resources to ease racial tensions in Hartford.” (Knapp 342). Students were encouraged to attend the funeral and professors held vigils and provided texts for students to analyze the violence against black people in America. On April 7, 1968, the student body urged trustees to use the Senate funds and create a scholarship for black students and other disadvantaged students for students in the Hartford and New Haven area and to incorporate black history to Trinity’s curriculum. After much debate, and students even willing to have some of their activities fund cut, the scholarship was able to pass on April 23, 1968. Students held a sit-in, wrote letters and even delivered them to the office to make sure that black students got the same opportunity as them to receive a liberal arts education.

This is one of the biggest pushes from the national level that, in turn, started to gain the attention of Trinity students on campus. Students felt as if Trinity could be doing a lot more than the bare minimum for black students. In the second part of their proposal, the Senate stated that Trinity needs a closer relationship with St. Paul’s College in Lawrenceville, Virginia, which is a predominantly black college. Trinity offered to help reshape their curriculum by integrating black history into their curriculum for credits. One of the things I noticed while reading this part of the book is that Trinity was pretty much hands-on comes it comes down fixing an issue. Trinity was able to recognize its privilege and decided to become an ally for marginalized students and even their schools. It’s kind of disappointing to see that the administration didn’t fully commit to their agreement. Looking back now, I wonder what happened to the plans of adding black history Trinity’s curriculum.

NEW ERA AT TRIN

Once President Jacobs retired, the Trustees began the search for his replacement. After much debate and an impulsive decision from Trinity, Dr. Harold J. Lockwood was elected president on July 1, 1968. Much like his proceeder, President Lockwood emphasized the importance of a liberal arts education and also mentioned the need for inclusion. In his inauguration he mentioned that Trinity needs to be an atmosphere where its members have are:

“openness to ideas, debate, and dissent

… commitment to the search for

truth, beauty, and understanding

[and) genuine concern for the individual,

whatever may be his or her race or creed.”

(Knapp 330)

This happens to be one of my favorite quote from the book because it’s not telling the student body to go out, find a black person and convince them to attend Trinity but it was more about helping others understand the importance of higher education. Especially during the civil rights movement, black students at Trinity felt as if they had taken on the “black activist” role, which in turn didn’t attract a lot of other black students to apply to Trinity. African American students didn’t want to go to college to defend why they belong in that institution or represent the entire black population. They just wanted to attend college and receive an excellent education. On campus, the black student felt that pressure, they wanted to create that space for incoming black freshmen. Black students were able to unite and create an organization called the Trinity Association of Negros (TAN), this organization ceased to make sure that incoming black Trinity students didn’t feel out of place.

By this point, Trinity knew that if they wanted students to attend the school they will have to accommodate to their needs. For starters, Trinity implemented a new program into the admissions system called a Freshman-Sophomore Honors Scholar Program. The program paired a sophomore with an incoming freshman to help them adjust to Trinity’s curriculum and just the school in general. From students to educators to administration, everybody was on board to continue promoting an inclusive education at Trinity. The second program was directed at public school high school students in New York City, that are in good academic standing and had the potential to excel in higher education. Admission doing tours around the country to inner-city schools and public schools in urban areas, Trinity was able to spread the word about the new mission of the college. The rate of black students enrollment at Trinity was increasing and by 1970, that was a total of 87 black students attended Trinity college as undergraduates, making 6.8 percent of the student body of 1,493( Knapp 340)

Nevertheless, black undergraduate students showed concerns that Trinity was incapable of providing a comfortable space for students which continues to discourage students from applying. In hopes of starting a conversation about campus life for black Trinity students, Trinity Coalition of Blacks, which is now known as Imani, and the Trinity Coalition of Black Women Organization continued to celebrate their identities and culture. The organizations used the spaces on 110-112 Vernon Street designed by the college as the Black Cultural Center in 1970. The center was later relocated to 74 Vernon Street and renamed the Umoja House (Knapp 473). This house fosters students from underrepresented backgrounds, especially those of African American descent. Students of color were able to finally create a safe space where to meet, discuss new ideas and be surrounded by people who share similar backgrounds as them.

In the early 1980s, Trinity College was flourishing as a higher institution under the presidency of James F. English Jr. At his inauguration speech on October 3, 1981, President English “placed particular emphasis on Trinity’s urban location” and the need to continue helping out in the community (Knapp 468). His most important point is that Trinity is open to Hartford students from all backgrounds and that Trinity is “seek[ing] a student body which reflects the diversity around us.” (Knapp 468). Post the Industrialization Era, Hartford had become predominantly black and Latainx population.

Even with all its efforts, Trinity’s student body remained predominantly white. Under the President’s administration curriculum reform, fundraising campaign, and implementing new technologies in the curriculum and enhance the Hartford-Trinity relations. Although Trinity was thriving, there was a decline in the enrollment of students of color but expanding the diversity of the student body remained the goal for Trinity’s admission. In the mid-1980s, Trinity’s enrollment for students of color started to soar yet again.

By 1989, admissions started revisiting some of their strategies from the late 1970s by visiting public high schools in urban areas with higher percentages of minority students. Trinity was always working towards recruiting more students of color on to their campus, but why wasn’t the administration working towards making sure that the programs they have in place are effective and are running to their full potential. Although I believe that new tacts bring in new people, the old programs just need a little tweaking to see better results.

Connecting Black Students to Black Alumni

Trinity wanted its students to excel beyond their years on campus, by helping them create networks with previous graduating classes. This was hard especially for black graduates, who were thrown into the workforce and were scared to look back at college. In regards to alumni programs, Trinity decided to host its first Black Alumni Gathering in September 1990. Trinity wanted to strengthen the relationship between graduates and black alumni, especially on how alumni can be more involved in admissions. Connecting current students to black alumni is one of the key ways to foster a sense of community and a powerful network. This is one of the things I feel like Trinity needs to bring back in full force. Although I’m grateful for resources like The Career Development Center, I want to talk to somebody that similar experiences as I did at a predominantly white institution and will not shy away from explaining the challenge I might face as a black woman. For the 1900s, there is a lack of documented evidence on the enrollments of students of color but from the graph, we can conclude that students of color endured. At this point, Trinity was somewhat consistent in the admission rate for students of color, until the rise and then small decline between 1998-2000.

End of an Era

In 1999, Karla Spurlock-Evans is selected as Trinity’s first Dean of Multicultural Affairs. Dean Spurlock-Evans and the Office of Multicultural Affairs were a huge part in promoting diversity amongst members of the Trinity College community. The office tends to students from all backgrounds by promoting a cognitive dialogue and creates “initiatives to promote a campus environment that respects and celebrates diversity in all its dimensions” (Homepage). The office’s goal is to also “weave multiculturalism into the institutional fabric of Trinity College” by making progress in recruiting a diverse student population. Over the years, Multicultural Affairs was able to help increase diversity at Trinity college.

According to Dean Karla Spurlock Evans, of Multicultural Affairs for 19 years, Trinity started working with Posse in 2002, specifically with the New York City location. Posse is a non-profit organization that “identifies, recruits and trains students leaders from high school to form multicultural teams” whilst providing students with a full scholarship (Homepage). After selecting their scholars, Posse then has an intensive eight-month program to prepare students for college. Posse homepage displays a big quote “Diversity is the key to solving our country’s biggest problems”. The Posse is, by design, multicultural and include black, Asian-American, Latinax and white students, although over the years the greatest number of Posse Scholars have been black and Latinax. Up until recently, each year Trinity used to accept up to 10-12 students per Posse but then admissions started limiting the size of to only 10 students per cohort. I first heard about Trinity through the Posse Foundation. I had no idea where the school was let alone what they offered. After doing my research, I knew that I wanted to apart of this great institution. Through Posse, I knew that I will have a cohort, full of students who had the same drive and hunger for higher education as I did. Aside from that with Posse, I knew that I will have an on and off campus support system throughout my college career. Although I didn’t get past the final round for Posse, I’m proud to say that the majority of my friends are Posse scholars.

In 2004, Trinity partnered with QuestBridge, a non-profit organization that connects low-income students to higher education. QuestBridge provides a College Prep Scholarships for high school juniors and a National College Match programs for high school seniors. QuestBridge aims to revolutionize the way leading colleges and universities recruit talented low-income students and the way these students approach their educations and futures” (Homepage). With the two programs working with Trinity, In 2005 Trinity reaches 24% in the rate of students of color enrollment. In 2006 Trinity accepted 52.8% black applications compared to 42.3% of all but in an article written by the New York Times, trinity college was facing some racial tensions on campus. Some black students have complained that they were regularly stopped to show identification and even a Latainx professor was mistaken for a janitor. Students of color felt as if the school was indifferent towards their discomfort on campus. They took matters into their own hands and staged protests and called upon “college officials to improve social relations by taking steps such as spelling out a racial harassment policy in the student handbook and of course to broaden its financial aid in order to expand the sociologic diversity of the student body (Hu 2006). After that decline in the number of students of color, Trinity started working to improve and expand financial aid. Trinity wasn’ really do anything to help resolve the racial tension on campus. Instead, as David Calder ‘20 said, “they’re good at smiling and patting themselves on the back, but at the end of the day, nothing gets done”(Hu 2006). Dean Evans comes to Trinity’s defense saying that students are the only here for four years “but I’ve been here a long time, and I know every effort counts” (Hu 2006). Efforts do count but if there is plans or future logistics on how to take the issue, it becomes just a bandaid fix.

In a Trinity Tripod issue written on May 3, 2019, Trinity Announces End of QuestBridge Program Partnership, Trinity discontinued its relations with QuestBridge in 2016. According to a Tripod written in December 2016, in an Interview with Angel Perez, Trinity’s Vice President for Enrollment and Student Success, he reviled that Trinity has stopped its partnership with QuestBridge because Trinity was “spending an insane amount of money” ( Tripod 2016). Perez states that this actually will open up a bigger space in terms of admission because the money will be sued towards broadening Trinity’s demographics. Partnering with QuestBridge requires money and Trinity was paying $100,000 annually in “addition to Admissions staff travel expenses to QuestBridge events and training” (Tripod 2016). Perez hints at the idea that Trinity might partner with similar programs like Posse and QuestBridge in the near future.

In 2018, Trinity experienced one of the highest growth in the enrollment of students of color. With an increase in percent, making up of students from Posse New York and Chicago. New York Posse 18 is the last Posse cohort to be accepted from New York City but Chicago will still remain. According to a Tripod written by Marquis Brinkley, “with a total of 609 students, the class of 2022 is Trinity College’s most diverse class in history (Brinkley 2019). With over 70 countries being represented and 54% of students are just outside of the New England area. Students from class 2022 shared their concern that Trinity is cutting off yet another resource that was helping to provide access to higher education. Eliminating these resources will result in a decrease of students of color in the coming years.

Although Trinity remains to be a predominately white institution, they have continued to diversify the campus. Trinity should pride itself in taking the initiative to open their space for students of color from start until now. Over time, Trinity had implemented additional policies or strategies to their admissions to encourage students of color to apply. However, I’m disappointed to see that Trinity didn’t completely commit to some of its policies. I would love to take a class on African American History. Still, Students of color are still at a disadvantage when it comes to the unwritten rules of a liberal arts campus makes students of color feel unwelcome and as if they don’t belong. Trinity faculty and staff need to Trinity’s admission need to consider taking action towards making this space a lot safer for students of color, which will promote inclusiveness at the institution.

Bibilography

Van Dusen, Albert E. “Connecticut .” Internet Archive, New York, Random House, 1 Jan. 1961, https://archive.org/details/connecticut00vand/page/362.

Knapp, Peter. “Currents of Change .” Trinity College in the Twentieth Century: a History, Trinity College, 2000, pp. 327–430.

Knapp, Peter. “Prelude to the New Millennium .” Trinity College in the Twentieth Century: a History, Trinity College, 2000, pp. 468-525.

“History.” Trinity College. 08 Apr. 2019 <https://www.trincoll.edu/abouttrinity/history-traditions/history/>.

“Timeline Entries .” Finalized Timeline Entries Web, Trinity College , www.trincoll.edu/StudentLife/CampaignForCommunity/Documents/FinalizedTimelineEntriesWeb.pdf.

“Multicultural Affairs Office .” Multicultural Affairs Office, www.trincoll.edu/StudentLife/Diversity/MulticulturalAffairs/.

Brinkley, Marquise. “Class of 2022: The Last Members of Posse New York.” – Trinity Tripod, 11 Sept.2018,commons.trincoll.edu/tripod/2018/09/11/class-of-2022-the-last-members-of-posse-new-york/.

“Class of 2022: The Last Members of Posse New York.” – Trinity Tripod, 11 Sept. 2018, commons.trincoll.edu/tripod/2018/09/11/class-of-2022-the-last-members-of-posse-new-york/.

Hu, Winnie. “An Inward Look at Racial Tension at Trinity College.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 18 Dec. 2006, www.nytimes.com/2006/12/18/nyregion/18trinity.html.

“OUR 40 COLLEGE PARTNERS.” QuestBridge, www.questbridge.org/.

Cripps, Karla, and Cnn. “Homepage.” The Posse Foundation, www.possefoundation.org/.