The film “Race to Nowhere” was originally made because of Vicki Abeles’ concern for her own children after a thirteen year old girl committed suicide because of her schoolwork. The tragedy that was Devon Marvin’s death caused this mother to think more critically about her own children’s experiences in school. It takes a thoughtful and provocative look at the American educational system, why kids are under such stress, and asking the question “is it even paying off?” The answer, according to the movie, is absolutely not. “Race to Nowhere” chronicles the stories of many young people in the school system, some of which have had mental illness as well as physical manifestations of their extreme stress. It also interviews teachers and education reformers, questioning them on their thoughts on the system currently in place and, more importantly, how we can fix this disastrous problem.

The filmmakers of “Race to Nowhere” do not pinpoint one specific problem in the educational system, because every interviewee has a different idea of what that problem is. Some think the problem is too much homework while others believe it is the overemphasis of Advanced Placement courses. Different interviews in the film focus on different ages of children. There are problems in the film that are specific to elementary school children, or middle or high school students. However, the generally agreed upon issue is that there is an overarching theme of extreme pressure placed on students which causes an excessive amount of stress. This stress results in both mental illness and physical illness. One nineteen year old, Natalie, describes her experience with Anorexia Nervosa (Abeles 13:45). She cites the reasoning for the onset of her eating disorder as it giving her insomnia, which translated into having more time for homework. Her eating disorder became so severe that she was asked to leave her school, but decided to get her GED instead of dealing with the process of transferring. Dr. Ken Ginsburg, an Adolescent Medicine Specialist at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, says that most negative behaviors, such as eating disorders, are usually caused by stress (Abeles 15:09). These physical manifestations can also be seen in the countless reports of stress induced headaches and stomachaches from children starting at an early age. The second, but less emphasized problem was the fact that despite the pressure placed on children, we are still being outperformed by a number of different countries. The desired goal of the filmmakers is to create an educational system that emphasizes learning and the process of learning rather than just grades and tests. This system would allow students to think creatively and be invested in their own learning. It would also produce happier children that were healthier mentally as well as physically.

By doing things like eliminating homework, the SATs, and even abolishing grading, the hope would be that students would genuinely want to go to school to learn, and that would therefore increase their performance. Jay Chugh, a teacher at Acalanes High School in Lafayette, California, cut the assigned homework for his Advanced Biology course in half one year. The results of the AP tests were actually higher than any other year (Abeles 26:00.) This shows the necessity to reassess how we think students learn and question the hours and hours of homework assigned to high school kids every night. “Stop Homework,” which was founded by Sara Bennett (also interviewed in the film) makes a very strong case against homework. According to the foundation, countries like Japan, Denmark, and the Czech Republic assign very small amounts of homework, but are still among the highest scoring countries on performance tests. In addition, a study done at Duke University showed that there was “very little correlation” between the amounts of homework assigned to students and their performance in elementary school and middle school, and in high school it was found that too much homework caused more harm than good.[1]

One critic of the film, Washington Post writer Jay Matthews, argues with Abeles, saying that as opposed to too much homework, students are receiving too little. He also complains that the film focuses “not on data but feelings.” He also disagrees that low-income students face large amounts of academic pressure.[2] This complaint is in response to a scene in “Race to Nowhere” where a character named Isaiah discusses his specialized struggles as a high school student living below the poverty line (Abeles 44:00). Isaiah’s interview pans his apartment, showing how poor his living conditions  are. Isaiah describes his massive amounts of homework, as well as the pressure he feels to rise above his neighborhood. He says that his counselor told him he needed to take Advanced level courses if he wanted colleges to even look at giving him scholarships. He took Advanced Environmental Science and received a D (Abeles 44:54). He also sites that he cheated multiple times throughout his college career to cope with his stress (Abeles 45:00). This scene shows that even in urban, impoverished schools, students are still getting a lot of work and are under an incredible amount of pressure.

are. Isaiah describes his massive amounts of homework, as well as the pressure he feels to rise above his neighborhood. He says that his counselor told him he needed to take Advanced level courses if he wanted colleges to even look at giving him scholarships. He took Advanced Environmental Science and received a D (Abeles 44:54). He also sites that he cheated multiple times throughout his college career to cope with his stress (Abeles 45:00). This scene shows that even in urban, impoverished schools, students are still getting a lot of work and are under an incredible amount of pressure.

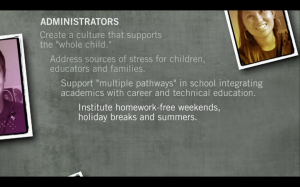

Just as there are many different problems brought up in the film, there are also many goals. The main two, however, are the improvement of the well being of children, as well as the increased performance of students. The policy chain in this movie can also be confusing because everyone has a different opinion. Education reformers and teacher bring different ideas to the table on how to improve our educational system. For families, Abeles says that, as a parent, she has begun asking her children less about school work, and creating conversation in other ways (1:13). Dr. Deborah Stipek, Dean of the School of Education at Stanford University, tells us that there is no easy fix for our system, but that we need to fundamentally change our culture and our expectations of students (Abeles 1:16.) Reformers like Sara Bennett suggest eliminating homework, or even abolishing grading, because of an ethical responsibility for the well being of our nations children (Abeles 1:16). Dr. Madeline Levine commends schools for eliminating Advanced Placement courses and colleges for changing the way they require SAT scores (Abeles 1:17). The hope through all of these actions is that students will have less work, and will therefore be less stressed and will enjoy school more. Through this, they would be more invested in their learning and their performance would improve.