The landmark Connecticut Supreme Court case, Sheff v. O’Neill, filed in 1989 on behalf of children in the Hartford school district, was monumental in working towards erasing segregation in Hartford schools. This case was filed on the basis that Hartford children, who were overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic, were receiving an unfair public education because of the racial and socioeconomic segregation that separates the city from the suburbs 1. The suit, filed by the parents of these children, looked to desegregate the Hartford public school system. At the time of filing, lead plaintiff, Milo Sheff, was a ten year old Black child living in Hartford with his mother, Elizabeth Horton Sheff, and attended fourth grade at the Annie Fisher School 2. Along with the parents of the eighteen other plaintiffs, Elizabeth Horton Sheff worked tirelessly to ensure that all children in Connecticut would have access to equal schooling. Although this historic Connecticut school integration case is named for her son, Elizabeth Horton Sheff originally became apart of the case by accident, yet over time grew to become its most vocal activist.

While some might call her an “accidental plaintiff” since she was not initially supposed to attend the community meeting discussing the racial isolation in Hartford schools, Elizabeth Horton Sheff’s work for Connecticut children is nothing short of remarkable. Even though she did not have a history of being involved in education inequality issues, she was a long time activist for “justice for people with HIV/AIDS, housing security, food security, and the anti-apartheid movement” and prior to her involvement in the case, had always been an extremely civic minded person 3. Elizabeth Horton Sheff grew up in the former Charter Oak Housing Project, which she “lovingly refers to as the…Wal-Mart plaza on Flatbush Avenue,” a neighborhood that had “all different families, racial ethnic families, West Indian, Hispanic, Italian, Asian… [and] what made it so very special was that families knew families and took care of each other’s children 4.” While she might have grown up in a single parent household where her mother worked a lot of long hours, she notes that growing up in a community where people cared about each other led her to have a wonderful childhood. She describes her mother as a woman who “worked very hard to ensure that [they] didn’t understand how very poor [they] were and… that is the basis that led [them] all to be confident youth and person who have excelled in adulthood 5.” Elizabeth Horton Sheff’s prior training as an activist helped shape her involvement in the Sheff case. Much of her training comes from her work as the Vice President of the Westbrook Village Tenants’ Association, which is a public housing development that she raised her children in in the northwest corner of the city 6. When the president of the association was invited to discuss the growing racial isolation in the city schools by civil rights public interest attorneys and local attorney, John Brittain, she asked Elizabeth to attend instead due to fear of some political pushback since she had a child in the Project Choice program. Elizabeth agreed to go because of her interest in public education and take some notes for her friend and as she says fondly, “23 years later, I am still taking notes 7.”

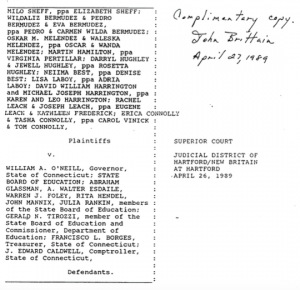

Lead Plaintiff Elizabeth Horton Sheff describes her involvement in the Sheff vs. O’Neill (1989). Source: Trinity College Digital Repository

At the meeting, “the lawyers highlighted the growing racial and economic isolation and resulting disparities in educational outcomes faced by children in the Hartford public school system 8.” What Elizabeth Horton Sheff heard at the meeting changed her life and immediately she knew she wanted to be more than just a notetaker for a friend. That night she learned that 91% of Hartford’s students were members of minority groups compared to less than 4% in Avon, 3% in Canton, 4% in Suffield, 6% in Simsbury, and 5% in Glastonbury 9. While she knew that she lived in a segregated area, she did not realize it was this extreme. She did not realize that 48% of Hartford’s kids came from poor families, compared to the just 2% in West Hartford and 1.5% in Glastonbury 10. When the lawyers discussed the scores of the Connecticut Mastery test to give proof of these disparities one fact “still burns in [Elizabeth Horton Sheff’s] mind: in 1989, 74% of students in the eighth grade in Hartford public schools needed remedial reading services 11.” Time and again, as Elizabeth Horton Sheff tells her story with remarkable consistency, she says that to her this did not mean that 74% of students were failing, but rather that the system was failing 74% of our children 12. She notes that she loves to read and is a mother who always reads to her children, and she was “dumbstruck by the reality that these children could reach the eighth grade without being able to read 13.” After this meeting and hearing the alarming statistics, she knew she had to go home and talk to Milo about getting involved. After Milo attended the next meeting, he agreed to sign on to be considered as a plaintiff for the case, as did many other families. All the families were interviewed and the lawyers picked ten to join the case, including the Sheff family. After a second interview, Milo and Elizabeth were asked to be the named plaintiffs. For the lawyers this was an easy choice. Not only did they have Milo who was a “handsome kid, like a little angel,” but they also had his mother who they deemed “perfect” and someone who was so committed to fighting for justice that they felt “lucky” to have her as a part of their team 14.

Milo agreed to be a plaintiff in the Sheff case because of the inequities and isolation he was seeing in his own school and the city schools around him. Even though Milo had never had any terrible instances in his school that his mother could not handle, it was apparent to both Milo and Elizabeth Horton Sheff that there were children in the Hartford public schools who were not being given the best education possible.

While Milo and his mother were named the lead plaintiffs based on Elizabeth’s status as a single mother, person of color, and ability to be extremely articulate, they were not the only ones actively fighting for change 15.When the case was filed in 1989, there were nineteen children representing ten families. These families were African American, Hispanic, Jewish, and of European ancestry and their socioeconomic status ranged from just making ends meet to living quite comfortably 16.The families lived in different neighborhoods both inside and outside of the city. Even though each family was different, they all had some history of activism in their communities and deeply believed in fighting for “equal access for all children to high-quality, integrated public education 17.” These families “bonded from the beginning” and to this day remain committed to the Sheff movement 18.

The Sheff case was filed in April 1989. The basis for the case revolves around three provisions of the Connecticut State Constitution:

Source: Trinity College Digital Repository

Article First, Section 1, which declares all people are equal; Article First, Section 20, which prohibits segregation and discrimination; and Article Eighth, section 1, which mandates “free public elementary and secondary schools” and names the Connecticut General Assembly responsible with ensuring this social benefit for all children 19.The case made three legal claims of inequality that proved that Hartford Schools were failing its students. These claims were:

- The educational achievement of children in the Hartford school district is unequal to the nearby surrounding communities and “the State of Connecticut, by tolerating school districts sharply segregated along racial, ethnic, and economic lines, has deprived the plaintiffs and other Hartford children of their rights to an equal educational opportunity 20.”

- The defendants “have long been aware of the educational necessity for racial, ethnic, and economic integration in public schools,” and have recognized the “lasting harm inflicted on poor and minority students by the maintenance of isolated urban school districts.” Yet despite their knowledge, they “have failed to act effectively to provide equal educational opportunity to the plaintiffs and other Hartford schoolchildren 21.”

- “The Connecticut Constitution assures to every Connecticut child, in every city and town, an equal opportunity to education” and “this lawsuit is brought to secure this basic constitutional right for plaintiffs and all Connecticut schoolchildren 22.”

Because this case involved advocating for Hartford children, the group worked with the lawyers to devise a legal strategy that would help the community. Together, as a coalition, they worked with the community to raise awareness and allow others to participate by lending their support. Elizabeth Horton Sheff is very adamant when she says that “[she] never did it for [her] child 23.” She goes on to describe how “Milo never went to a magnet school. He was out of school before we… really even got to that stage of now implementing a decision… but, I never did it for my child, I did it for our kids 24.” While many of the plaintiffs in the suit never saw much of the direct results of the rulings in the case in their schools, they maintained their commitment to the case in order to help all students, present and future, receive the best education they can, regardless of where they lived, their race, or their socioeconomic status.

“I never did it for my child, I did it for our kids.”

Through the long journey and wait for a ruling, the group worked tirelessly to gain the support of the local community in the city, as well as the suburbs. Through numerous meetings at churches, community centers, schools, government agencies, and many more, these plaintiffs stood strong with the overall goal to improve the education for Connecticut’s children. Even though the case lost in the lower court, the group appealed the decision to the Connecticut Supreme Court. In July of 1996, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled in their favor on the basis of Count 2, upholding the claim that segregation based on race and ethnicity in Hartford schools was a violation of the Connecticut constitutional rights of Hartford schoolchildren 25. The opinion read, “the public elementary and high school students in Hartford suffer daily from the devastating effects that racial and ethnic isolation, as well as poverty, have had on their education… we hold today that the needy schoolchildren of Hartford have waited long enough 26.” Along with this ruling, the court ordered the executive branch of the Connecticut General Assembly to execute its findings. Yet, even though the plaintiffs had this landmark Supreme Court decision, their fight did not stop there and they turned back to the community to continue fighting for social change for their kids and for the community to participate in demanding this change from the state. Even with this ruling in hand, the road to desegregated schools is long and hard, as the Sheff plaintiffs have seen, and the fight continues, to this very day. Yet even so, Elizabeth Horton Sheff and many others trudge on in search for equal education for all children of Connecticut.

Notes:

- Sheff v. O’Neill complaint (Connecticut Superior Court 1989). Available from the Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford, Connecticut (http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu) ↩

- Ib.Id ↩

- Sheff, Elizabeth Horton. Oral history interview on Sheff v. O’Neill (with video) by Candace Simpson for the Cities, Suburbs, and Schools Project, July 28, 2011.Available from the Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford Connecticut (http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp/). ↩

- Ib.Id ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Sheff, Elizabeth Horton. “Sheff v. O’Neill: The Struggle Continues against School Segregation and Unequal Opportunity.” Voices in Urban Education, 2004, 16-21. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Ib.Id ↩

- Ib.Id ↩

- Ib.Id ↩

- Eaton, Susan. The children in room E4: American education on trial. Algonquin Books, 2009. ↩

- Sheff, Elizabeth Horton. Oral history interview on Sheff v. O’Neill (with video) by Candace Simpson for the Cities, Suburbs, and Schools Project, July 28, 2011.Available from the Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford Connecticut (http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cssp/). ↩

- Sheff, Elizabeth Horton. “Sheff v. O’Neill: The Struggle Continues against School Segregation and Unequal Opportunity.” Voices in Urban Education, 2004, 16-21. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Shelf, Elizabeth Horton. “Sheff v. O’Neill: The Struggle Continues against School Segregation and Unequal Opportunity.” Voices in Urban Education, 2004, 16-21. ↩

- Sheff v. O’Neill complaint (Connecticut Superior Court 1989). Available from the Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford, Connecticut (http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu) ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Sheff, Elizabeth Horton. “Sheff v. O’Neill: The Struggle Continues against School Segregation and Unequal Opportunity.” Voices in Urban Education, 2004, 16-21. ↩

- Ib.Id. ↩

- Eaton, Susan. The children in room E4: American education on trial. Algonquin Books, 2009. ↩

- Sheff, Elizabeth Horton. “Sheff v. O’Neill: The Struggle Continues against School Segregation and Unequal Opportunity.” Voices in Urban Education, 2004, 16-21. ↩

Readers: please comment on the following questions, and feel free to add your own.

1) Does the essay tell a compelling story from the perspective of people at that point in time?

2) Does the essay make insightful claims about the past, supported with persuasive evidence?

3) Does this blend of text and digitized sources make you think about the topic in new ways?

Congratulations on a well written, engaging, and inspiring essay. You’ve done a great job presenting Elizabeth Horton Sheff’s story in a clear and concise narrative, while also managing to connect it with many of the core issues underlying this landmark case. You provide clear evidence of her sense of both outrage (with regard to the conditions of schooling for Hartford students) and obligation (to strive for a more just and equitable community) that informed her decision to join the suit. You note the remarkable consistency with which she has narrated her own story, and I was curious as to if there has been any variation at all in terms of how she has presented her “story” between 1989 and today (you use primarily interviews from the last 10 years or so).

Among the critical take-aways for me is the clear sense that Elizabeth Horton Sheff understood her actions as a defense not of the *individual* rights of her son, but as a *collective* action in support of a stronger and more equitable community. This is quite interesting as it suggests the possibility that the individual law suit is a somewhat awkward mechanism for broad social change. Given as well that Milo did not necessarily directly benefit from the results of the ruling (i.e. the remedy of the Magnet program), I wonder if there is any evidence of other ways being involved in the case had an effect on Milo and/or his relationship with his mother.

The inclusion of the photographs was helpful, and raised the question of how ‘iconic’ Elizabeth and Milo have become in this case and how the representation of them over time has changed. Milo seems often to be ‘standing by’ with Elizabeth speaking or at least facing the camera. What might this tell us about the dynamics of the case? I also enjoyed the link to the full oral history interview of Elizabeth. It might have been helpful to have a few suggestions as to the time codes where particularly revealing responses were given.