Source: Sheff plaintiffs memo, 2018.

Source: Sheff plaintiffs memo, 2018.

Over the last few days, I have discussed a number of aspects of the State of Connecticut’s efforts to racially desegregate schools. In short, the State uses voluntary school choice programs, such as magnet schools to create racially diverse educational settings. But over the past several years, a number of groups have launched a campaign against school desegregation. This post will break down the new Robinson case attempting to undo the civil rights gains made by the Sheff v. O’Neill case.

Earlier this year, parents that reside in Hartford, CT filed a federal lawsuit against the State of CT and Hartford Public Schools claiming that the State’s magnet lottery and reduced isolation definition were racially discriminatory and violated the 14th amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The parents and their lawyers allege that because their children have not been accepted to any of the State’s magnet schools, the State has discriminated against their children. To be clear, these are allegations and there is no actual evidence of racial discrimination in the documents, only a certain interpretation of State law. The parents are represented by the right-wing Pacific Legal Foundation that works to protect, “private property,” “economic liberty,” and “individual rights” (990 tax form).

This Robinson et al v. Wentzell case has been a focal point in the discussion about the State’s effort to desegregate schools. Through their lawyers, they are asking the federal court to stop the State magnet school lottery as currently designed and stop the use of a definition of reduced isolation used to deem magnet schools racially diverse or not. In other words, the Robinson case seeks to ultimately end the Sheff v. O’Neill school desegregation remedy as we currently know it in Hartford, Connecticut.

In response, the plaintiffs in the Sheff v. O’Neill school desegregation state case filed a motion to intervene in the Robinson federal case. Basically, the Sheff plaintiffs want to intervene because the Robinson case, poorly handled, could gravely impact the Sheff lawsuit. Also, the Sheff team believes that the State is a poor defendant of school desegregation remedies given that Governor and Legislature do not and did not want school desegregation in 1996 or in 2018.

The Sheff plaintiffs are represented by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which is a wing of the oldest civil rights organization in the U.S. that defends educational, economic, and racial justice (990 tax form). The Sheff plaintiffs argue that the Robinson case should be dismissed based on many incorrect facts and poor interpretation of the law. Furthermore, the Sheff plaintiffs believe that some of the issues raised in the Robinson case should be resolved in the Connecticut court in February 2019 when it takes up the State’s failure to comply.

Here it’s important to separate the people from the goals and arguments. As far as I can tell, the parents in the Robinson case are sincere in their concern for their children. They also show concern that magnet schools have limited enrollment. They aren’t alone in feeling frustration with the State’s efforts to deliver equal educational opportunity in all schools in Hartford and elsewhere.

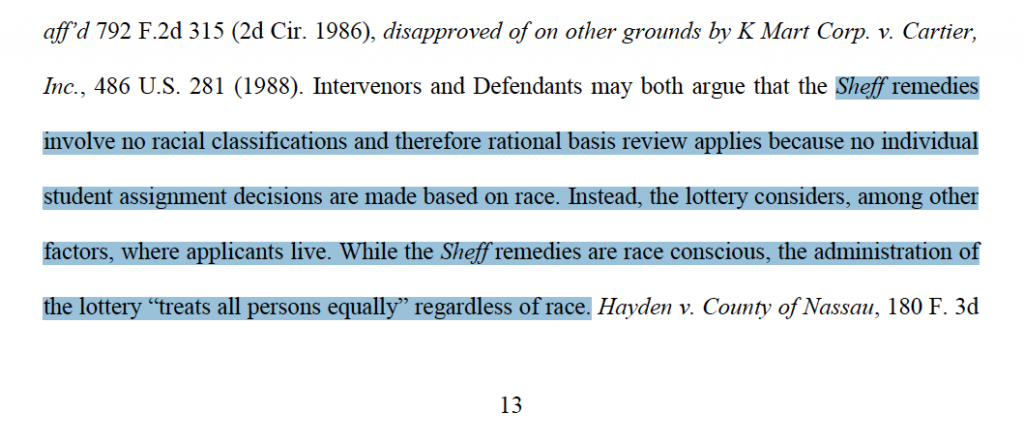

However, the Sheff lawyers make a strong argument that the Robinson case argument is wrong on the facts and the law. The lottery for magnet schools is race-neutral and the State defines a racially diverse school through a benchmark rather than direct mandates or limits of students of any particular race. These facts about the system make sure that the State develops racially diverse schools to counteract the effects of school and residential segregation without specifically using racial categories to make that happen. There are no “racial quotas” and children aren’t being denied magnet school enrollment on the basis of race.

So if the magnet lottery is race-neutral and the State only has a benchmark for racially diverse schools, then why is the Robinson group suing the State in federal court over the magnet system?

In the past, the Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF) that represents the Robinson parents has promoted charter schools and the elimination of school desegregation orders that are “race-conscious.” The PLF group has submitted court briefs defending private charter schools use of public facilities in California and other states and it was heavily involved in dismantling school desegregation in places likes Seattle in the Parents Involved case, for example (Sandberg, 2011).

In addition, the CT Parent Union has facilitated Pacific Legal Foundation’s work in Connecticut over the past weeks. In the past, the CT Parent Union has lobbied for a “parent trigger” bill that would allow parents to vote to turn their school into a charter or other privately-managed school.

As the New Haven Independent recently reported, Pacific Legal Foundation is still trying to find other clients beside the Robinson group to help them dismantle school desegregation in Connecticut. As the Independent reported, Pacific Legal wants to find parents in New Haven, ‘”in order to file a suit that could bring down the entire magnet program statewide.” According to the article, CT Parent Union is assisting that effort.

As a side note, it is helpful to look at where these organizations get revenue using public tax form data. It’s unclear where Pacific Legal Foundation gets its funding, but there are some hints that their money from corporations and foundation related to fossil fuel industries, plus other big businesses (No sources listed on 990 tax form). Similarly, it’s unclear how CT Parent Union is funded (no 990 tax form, might not be a 501(c)3 non-profit). The NAACP Legal Defense funds primarily obtains revenue through fundraising, investments, and grants from other civil rights organization. (990 tax form, 2017). The Shelf Movement is a 501(c)3, but does not yet have a 990 tax form.

So how does the Robinson case fit into the Pacific Legal Foundation and CT Parent Union agenda?

The Shelf plaintiffs have advocated “race-conscious” school choice policies as a means towards numerical school desegregation. Or, put another way, Sheff plaintiffs have advocated for school choice as a means towards a broader societal goal of racial integration. On the other hand, both Pacific Legal Foundation and CT Parent Union advocate for “school choice” as a goal by itself. They believe in “colorblind” choice that doesn’t specifically promote school diversity. The Robinson case would not require or guarantee the State to place more students in racially diverse magnet schools, but it could open the door for more charter schools, the “colorblind” version of school choice that PLF and CPU like more.

So, here’s a hypothesis.

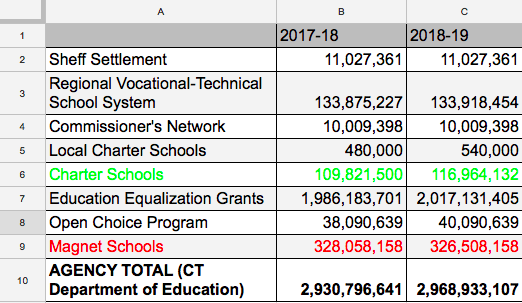

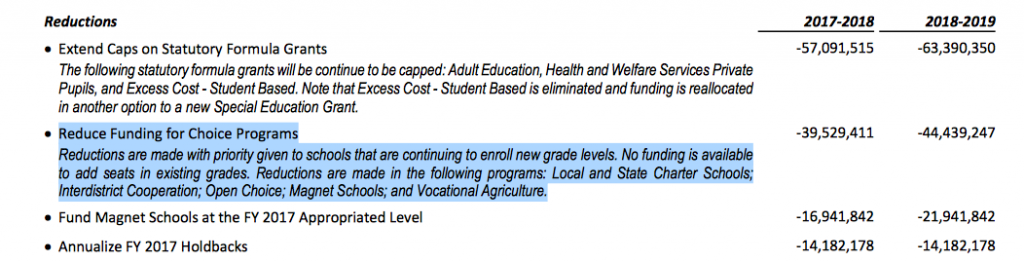

In Hartford, the Sheff case has used magnet schools as a way towards voluntary school desegregation. Connecticut’s magnet schools are racially diverse through a regional lottery, funding incentives and supports, plus their regional design. Diverse magnet schools in Hartford have thwarted racially segregated and privately-managed charter school growth in the city.

These privately-managed charter schools have grown in Hartford, but not as fast as in places such as New Haven and Bridgeport that do not have a court-ordered desegregation plans. Today, nearly all of the publicly-funded, privately-managed charter schools in Connecticut are racially segregated, lacking the rules and standards for racial diversity used as benchmarks for magnet schools.

If the Robinson case can dismantle the regional magnet school lottery and the reduced isolation definition in Hartford and New Haven, then that paves the way for more “school choice” without racial equity and other safeguards (UCLA Civil Rights Project, 2010). Down the road, that could mean more charter schools in Hartford. In other words, if the State doesn’t have to keep making racially diverse magnet schools in Hartford because of the Sheff remedies, then it would be free to open more racially-segregated, privately-managed charter schools.

Labor rules and public funds are in the background, but important issues too. Magnet schools are public schools that also have unionized teachers. Charter schools typically do not have unionized staff and teachers. Pacific Legal loves charter schools and is not too fond of unionized employees. For example, PLF submitted a supporting brief to undermine unions and working people in the Janus case. Without teachers unions and the same stringent rules for spending public funds as magnet and public schools, there is money to be made in segregated, privately-managed charter schools in a way that is not possible in public schools.

And, while it could just be a coincidence, it’s important to note that one of the plaintiffs in the Robinson case was a founding member of the Board of Directors for a charter school in Hartford that attempted to obtain state approval last year. The State of Connecticut rejected the application, for now (See the Community First Charter School Application to CT SDE, 2017).

This Robinson case is not happening in isolation. There is a broader campaign to dismantle school desegregation in Connecticut that has been brewing for a number of years. To be sure, this campaign exploits frustration by parents with poor implementation of school desegregation by the State of Connecticut and counter-productive education reforms over the last decade. Next, we will take a look at this campaign.

Views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Trinity College.