The LGBTQ+ community has faced discrimination within every field of work. Members of the LGBTQ+ community have been ostracised, ridiculed, and even discredited for their work within their respective fields. The discrimination faced is heightened within the STEM field. Although this field of research is new, we can still analyze the findings that the articles that have been released present.

Overall, each of the ten articles we researched concluded that members of the LGBTQ+ community who are also in STEM have faced greater discrimination than members of the LGBTQ+ community who are not in STEM. LGBTQ+ STEM professionals have been quoted saying they have felt included, harassed, and ridiculed during their work. (Cech and Waidzunas, 2021). Members of the LGBTQ+ community who are not in STEM have not experienced as much discrimination as members in STEM (Cech and Waidzunas, 2021). Each article focuses on different aspects of the same outcome. One article stated that gay men are 12% more likely to be driven out of the STEM field in comparison to straight men within the same field (Nishat, 2019). Although women within the LGBTQ+ community face hardships and discrimination, they are 2% more likely to join the STEM field (Nishat, 2019). Another study shows that there is significant occupational gender composition, which appears to influence the choices of LGBTQ workers, a majority in gay men and lesbian women (Finnigan, 2020).

There are some policies that could come into place to fix the divide between LGBTQ+ professionals in STEM and non-LGBTQ+ professionals in STEM. LGBTQ+ professionals in the nursing field have said that there needs to be some sort of education period for “higher-ups” in the medical field (Eliason, 2011). Higher-ups have been remarked as “unfriendly” and not willing to accept the members of the LGBTQ+ community within their field (Eliason, 2011). An education period for members in every field of work could help benefit members of the LGBTQ+ community, which could lead to the acceptance and lack of discrimination that they are seeking. A policy surrounding the credit for work that has been done could be put into place as well. As stated before, LGBTQ+ members in STEM have been often discredited for their own work/findings solely because of their sexuality. Another policy could be in place to help assure these members of STEM that their work will be recognized regardless of their sexual orientation.

If policies in regards to the equal treatment of LGBTQ+ professionals in STEM do not come into place, then there will be even more of a decline in the amount that want to work within this field. It may seem like a small total as of right now, but if the trajectory that this is on stays the same, then there will be less representation of LGBTQ+ workers in STEM and other working fields. This could turn out to have long-term negative economic effects, seeing that there was starting to be more of a presence of LGBTQ+ in STEM. Without the equality they deserve, they are going to leave the field, which the STEM field will suffer from in the long run.

Research Questions

- What needs to be done policy-wise to encourage the government to keep data on LGBTQ+ professionals in STEM?

- Why are women within the LGBTQ+ community more likely to be in STEM than men in the LGBTQ+ community?

- How can LGBTQ STEM organizations and groups contribute to the sense of community and belonging for LGBTQ+ individuals in the STEM field?

Citations

Cech and Waidzunas, Systemic Inequalities for LGBTQ Professionals in STEM – Science, www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abe0933. Accessed 19 Oct. 2023.

Eliason, Michele J., et al. “Https://Www.Sciencedirect.Com/Science/Article/Abs/Pii/S8755722311000329?via%3Dihub.” Science Direct , www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S8755722311000329?via%3Dihub.

Nishat, and Please enter your name here. “New Data Examines Presence of LGBTQ People in Stem.” Open Access Government, 19 Nov. 2020, www.openaccessgovernment.org/lgbtq-people-in-stem/98054/.

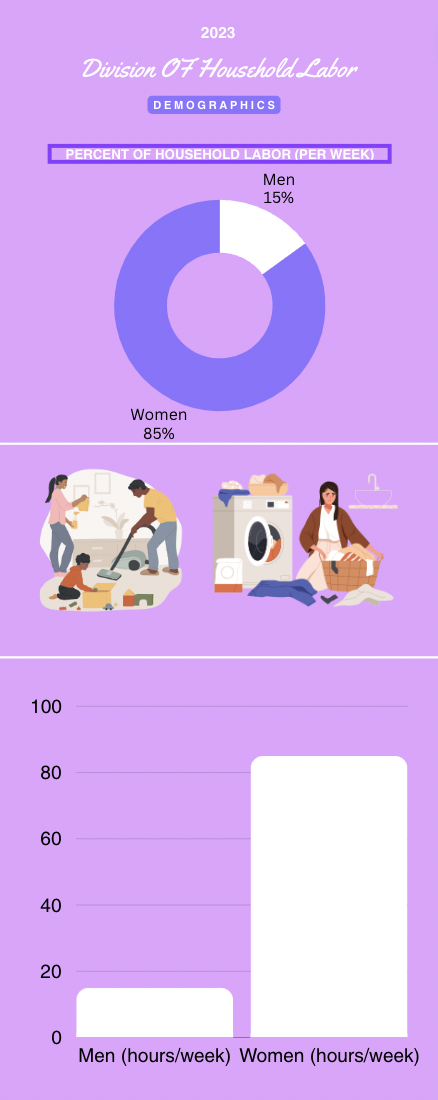

This imbalance has persisted across cultures, perpetuating the stereotype that housework is primarily a woman’s domain. However, it’s essential to recognize that these gender roles are not always present. These gender roles depend on multiple factors such as the education and occupation of both men and women, as the partner with no occupation might have more time spent in the household. This blog post dives into the correlation between the education level and career choice of men and the amount of domestic labor they participate in.

This imbalance has persisted across cultures, perpetuating the stereotype that housework is primarily a woman’s domain. However, it’s essential to recognize that these gender roles are not always present. These gender roles depend on multiple factors such as the education and occupation of both men and women, as the partner with no occupation might have more time spent in the household. This blog post dives into the correlation between the education level and career choice of men and the amount of domestic labor they participate in.