By Matt Almansi and Ian Coffey

Summary of Issues

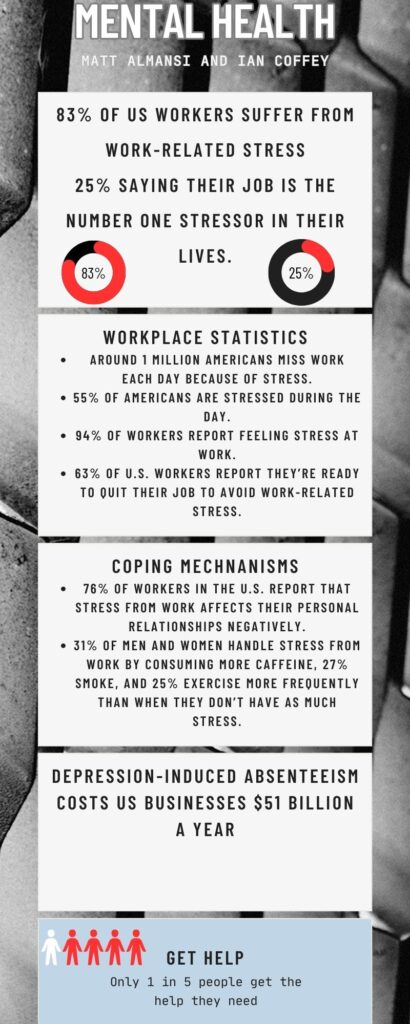

Mental health is something everybody has to deal with, one large factor surrounding poor mental health is the pursuit of employment. The use of the word “pursuit” is important because mental health issues arise not just from the stress of working, but also in the process of looking for jobs and being unemployed. Men’s and women’s mental health are both affected by their job or lack thereof but how it is experienced or shown varies between the genders. Five major symptoms of poor mental health include depression, anxiety, somatization, chronic fatigue, and psychotropic drug consumption. These symptoms tend to show up more often, unsurprisingly in high-stress jobs and when compounded with inadequate compensation or support these symptoms are only worse for both men and women. Beginning in the 1980s research on job-related stress has taken off. One of the key findings is that when resources available to the worker are adequate for the demands in the workplace then the mental health of the worker is protected. On the other hand, when the demands of the workplace exceed the resources available to the worker it creates a strenuous atmosphere, and the mental health of the worker becomes compromised. Although men and women both experience mental health issues in the workforce, the roots of their problems differ.

Policy Recommendation

It is hard to force or implement policies regarding what companies should pay their employees but people need better support in the workplace. It is clear that currently corporations do not do nearly enough to give back to their employees, but have no problem profiting from them. Two sound options emerge that the government or individual companies could implement for the betterment of the work culture and employees. The first is that if an employee works over a certain amount of hours in a month, then he or she is entitled to a mandatory day off at some point next month and does not have any effect on their structured PTO days. The second is for those who work in high-strenuous jobs to have medical benefits expanded to include mental health resources such as access to a psychologist or psychiatrist. The implementation of one or both would serve to treat and mitigate the negative health consequences in the workplace. This could take the form of an outright law companies must implement or through tax breaks, they can get by treating their employees well.

Consequences Without Intervention

Without the implementation of our proposed policy, the economy will be in a constant state of underperformance or unsustainable growth. Truth be told, there may not appear to be much change in day-to-day life if this policy is not put in place. However, society and the economy would improve drastically if workers felt better about themselves and thus the work they do. Mental health is a very important aspect of a worker’s ability to maximize productivity. At our current juncture, the U.S. economy is performing well, but that is not to say it could not be performing better. By implementing our proposed policies we theorize that workers will feel less burnt out and thus more productive. If nothing is done for the mental health of our workers, nothing will change drastically for the worse, there will always be someone willing to put themselves through the mental agony of a high-stress job. But if the mental health of employees is taken into account there will only be added benefits. Workers will feel more support in their workspaces, won’t feel as burned out, and will not display symptoms of poor mental health such as anxiety, depression, somatization, chronic fatigue, and drug use as frequently.

Research Questions

- Is work stress an isolated national problem or a global problem?

- Are there, and if so, what are the policy differences between countries that have workers with good mental health vs countries with mentally unhealthy workers

References

- Godin, I., Kittel, F., Coppieters, Y. et al. A prospective study of cumulative job stress in relation to mental health. BMC Public Health 5, 67 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-67

- Strandh, Mattias, Anne Hammarström, Karina Nilsson, Mikael Nordenmark, and Helen Russel. “Unemployment, Gender and Mental Health: The Role of the Gender Regime.” Sociology of Health & Illness 35, no. 5 (2012): 649–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01517.x.

- Peckham, Trevor, Kaori Fujishiro, Anjum Hajat, Brian P. Flaherty, and Noah Seixas. “Evaluating Employment Quality as a Determinant of Health in a Changing Labor Market.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences5, no. 4 (2019): 258–81. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2019.5.4.09.

- Tesch-Römer, Clemens, Andreas Motel-Klingebiel, and Martin J. Tomasik. “Gender Differences in Subjective Well-Being: Comparing Societies with Respect to Gender Equality.” Social Indicators Research 85, no. 2 (2008): 329–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27734585.