Summary of Findings

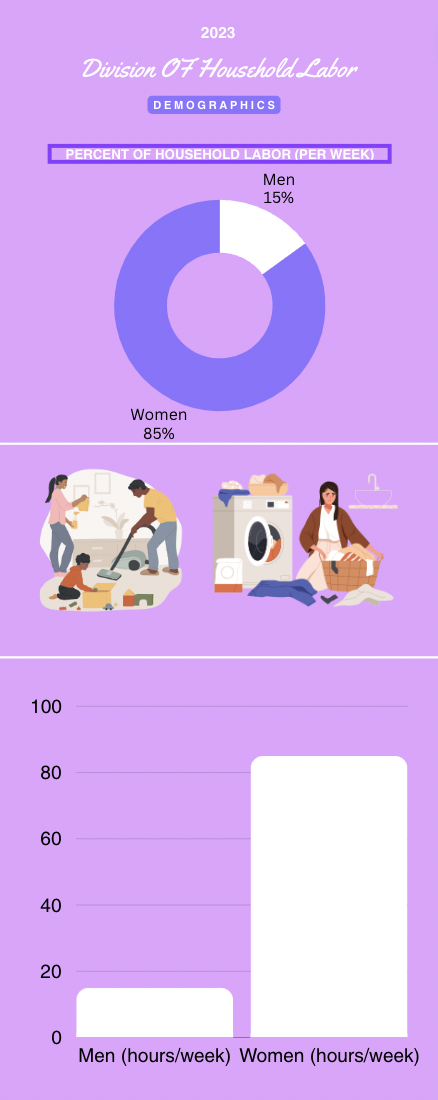

For centuries, societal norms have prescribed a division of labor within households, often leaving women taking on the majority of domestic responsibilities. Traditionally, tasks like cooking, cleaning and caregiving have been deemed “women’s work,” while men have been less involved in these duties.

This imbalance has persisted across cultures, perpetuating the stereotype that housework is primarily a woman’s domain. However, it’s essential to recognize that these gender roles are not always present. These gender roles depend on multiple factors such as the education and occupation of both men and women, as the partner with no occupation might have more time spent in the household. This blog post dives into the correlation between the education level and career choice of men and the amount of domestic labor they participate in.

This imbalance has persisted across cultures, perpetuating the stereotype that housework is primarily a woman’s domain. However, it’s essential to recognize that these gender roles are not always present. These gender roles depend on multiple factors such as the education and occupation of both men and women, as the partner with no occupation might have more time spent in the household. This blog post dives into the correlation between the education level and career choice of men and the amount of domestic labor they participate in.

Interestingly, studies suggest a correlation between a man’s education level and his involvement in domestic labor. Higher education often correlates with a greater likelihood of sharing household responsibilities. Men with more education tend to be more open to challenging traditional gender roles and participating more actively in domestic tasks. Studies show that men with a college education or higher were reported to spend approximately 8 hours per week on housework, compared to around 5 hours for men with a high school education or less. This correlation could be present due to the more consistent hours these men are working, which is most likely 9am-5pm. This stability will leave these higher educated men more energy and time for household duties. On the other hand, men with a lower education level are often in the situation of working longer hours, including overtime, which would push their work day over ten hours long. In this scenario, at the end of the workday, these working men are exhausted and do not have enough energy to perform household labor. However, this correlation isn’t absolute, as individual attitudes, upbringing, and societal influences also significantly shape one’s approach to household labor regardless of educational background.

With these findings, it is also important to look at women and the correlation between their education level and career with the amount of domestic labor they do. It is found that highly educated women tend to do less housework than those with lower education levels, but like men, they prioritize childcare responsibilities. On average, women with college degrees spent around 7-10 hours per week on housework, whereas those without a college education spent approximately 13-17 hours per week. These findings emphasize the complexity of household dynamics, and shed light on the factors like education, societal norms, and the allocation of tasks, that affect the division of household labor between married couples. These findings prompt discussions on evolving gender roles and the need for more equitable distributions of responsibilities within modern households.

Although the results across studies show that improvements to the gender inequality in division of labor have certainly been made, men are increasingly more likely to do their share of household labor in recent years. However, one might argue that since the majority of the data we collected from case studies was conducted in the U.S. where cultural norms surrounding marriage and gender are progressive. Therefore, if the data was to be collected from second and third world countries the results could be very different. The general attitude and cultural norms surrounding women and marriage in these countries are more traditional and idealize the man being the ruler of the household. Therefore the women are left with all of the household labor, resulting in an unequal division of labor.

Policy Recommendations

Flexible work hours and extended parental leave policies play pivotal roles in addressing the gendered division of labor within households. By advocating for flexible work schedules, particularly for professions requiring extended hours, both men and women can better manage their professional commitments alongside household responsibilities. This adaptation allows individuals to participate more actively in domestic duties without compromising their careers. Simultaneously, advocating for extended and equal parental leave policies ensures that men are encouraged and supported to take on more substantial caregiving roles during the crucial early stages of a child’s life. This not only fosters bonding between fathers and their children but also helps challenge traditional notions of childcare being predominantly a woman’s responsibility. These policies collectively contribute to breaking down societal barriers and fostering a more equitable division of household labor between genders.

Potential Consequence without Intervention

Without intervention, the continuation of traditional gender norms surrounding household labor could deepen, reinforcing the existing imbalance in domestic responsibilities. The persistence of these norms across cultures sustains the stereotype that housework primarily belongs to women, solidifying the societal belief that certain tasks are inherently feminine. This perpetuation not only limits the opportunities for men to actively engage in household chores but also burdens women with an unequal share of domestic duties, regardless of their educational or career achievements. In settings where cultural norms idealize men as the primary authority within households, the absence of intervention could solidify these gendered divisions, leaving women to bear the brunt of household labor. Such unaddressed disparities might delay progress towards more equitable distributions of responsibilities within households, perpetuating a cycle of inequality across societies, especially in regions where cultural attitudes toward gender roles remain deeply traditional.

Research Questions

Question 1: Are college educated women who obtain a high wage occupation more likely to stay single than other women?

Question 2: Is there any difference in division of labor at home between heterosexual couples and homosexual couples? If so, is this division between male couples different from that of female couples?

Question 3: What cultural beliefs affect who takes on more household responsibilities in different countries, and how does this influence the division of labor between genders?

References

Catherine E. Ross, The Division of Labor at Home, Social Forces, Volume 65, Issue 3, March 1987, Pages 816–833, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/65.3.816

Farkas, George. “Education, Wage Rates, and the Division of Labor between Husband and Wife.” Journal of Marriage and Family 38, no. 3 (1976): 473–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/350416.

Chiappori, Pierre-André, Murat Iyigun, and Yoram Weiss. 2009. “Investment in Schooling and the Marriage Market.” American Economic Review, 99 (5): 1689-1713. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.99.5.1689

Baker, Matthew J., and Joyce P. Jacobsen. “Marriage, Specialization, and the Gender Division of Labor.” Journal of Labor Economics 25, no. 4 (2007): 763–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/522907.

Sanchez, Laura, and Elizabeth Thomson. “Becoming Mothers and Fathers: Parenthood, Gender, and the Division of Labor.” Gender and Society 11, no. 6 (1997): 747–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/190148.