Written by : Himena Yamane and Georgia Fales

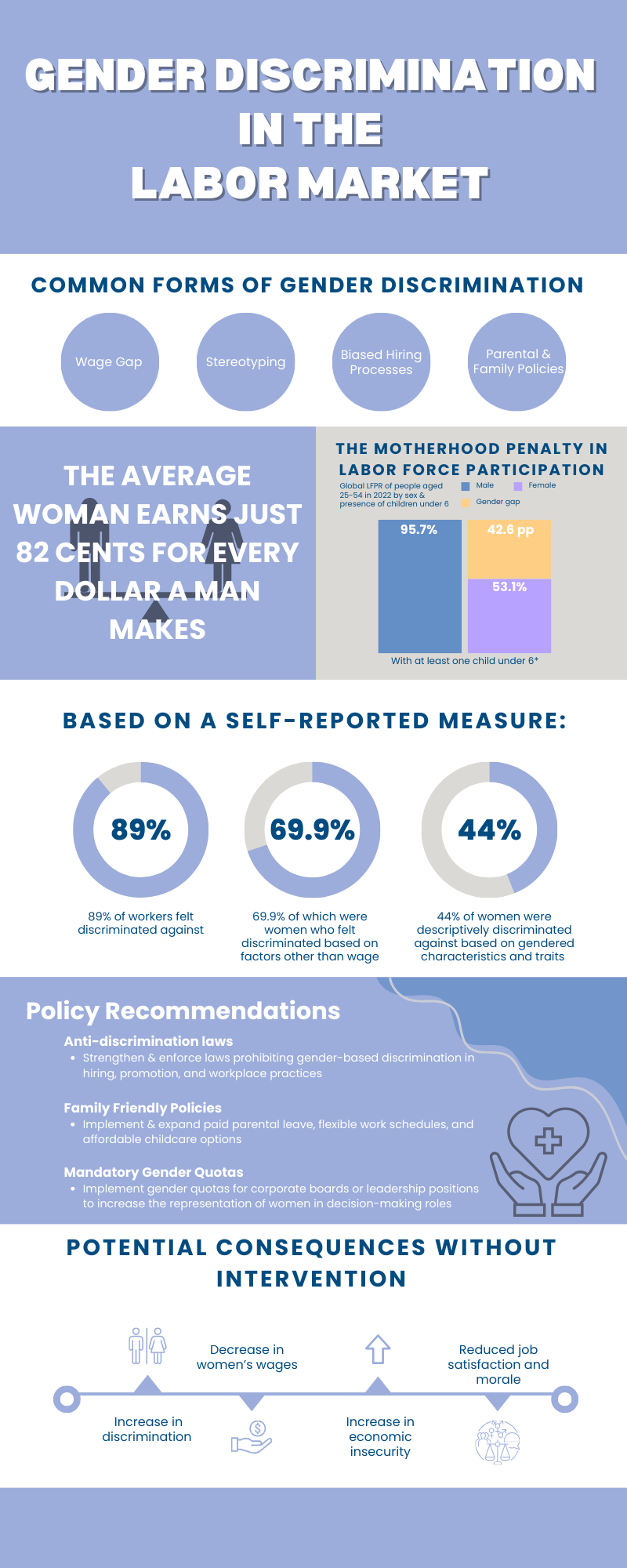

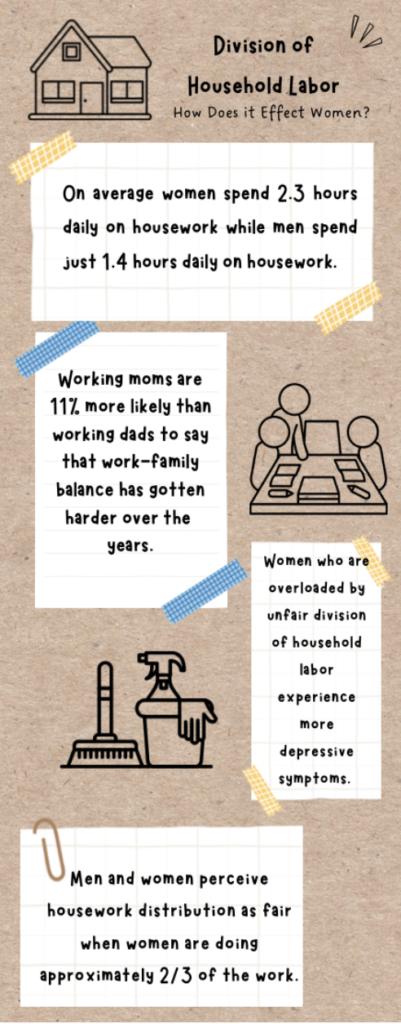

The division of labor within households has been a longstanding issue influenced by income, family composition, and deviance neutralization. Although there has become more progression in the equality of household labor disparities persist and have caused long-lasting effects on women. Effects on women can be seen through the wage gap, retention in the labor force, and traditional gender norms that still exist today.

Many factors influence how the division of labor is distributed. Driving factors such as family composition, income, and participation in the labor force have a substantial effect.

Traditional gender norms has a major effect on the division of labor within households. According to Economic dependence, gender, and the division of labor in the home (Theodore N. Greenstein, 2000) a study showed that in homes that have a male as their source of primary income, there is a higher likelihood that the household labor disparities are larger. In the case that women are the main source of income, there seemed to be a less but similar response with the process of deviance neutralization to counteract those nontraditional norms causing high household labor disproportion. With women taking on more household jobs, as a result, they are less likely to be part of the labor force which in turn widens the income gap and workforce gap. Even when women make more money than the male in a household, gender norms drive women to still taking on more household labor.

Family composition can also highly drive the disparities of household labor. Household labor is more than just cleaning and cooking but can also include stressful parental duties. In The Parenthood Effect on Gender Inequality: Explaining the Change in Paid and Domestic Work When British Couples Become Parents (Katherine Michelmore and Sharon Sassler, 2016) there seemed to be a reoccurring pattern of women, pre-children, who made higher income tending to have higher retention in the labor force while women, pre-children, who had a lower income had lower retention in the labor force and spent more time dedicated to household chores and parental responsibilities. This pattern can explain the complexities of becoming a parent with different incomes and the responsibilities that are traditionally passed to the mother. With fathers not usually taking on household chores, like being the main caregiver for a child or children, women are deterred from the labor force when they do not have the economic necessities for childcare or support.

Childcare policies and other policies that challenge gender norms are needed to help change the disparities in household labor and the labor force. Paid leave policies need to be more accessible in all different occupations to support a family’s responsibility in the context of becoming a parent. Affordable childcare policies also need to be implemented to help retain women in the labor force after becoming a parent to minimize disproportions in the labor force and therefore equalize household responsibilities. Promoting more gender equality in aspects of household and labor market, such as equal pay wage, is also needed to help with these enduring complex issues regarding the division of household labor. The implementation of these policies can contribute to a more equitable distribution within the household and the labor market.

Without the implication of these policies we will see a further gender divide in many aspects. Catherine Ross ( 1987), in The division of labor at home, revealed that when analyzing couples with less of an income gap, the distributions of household chores were more equal while couples with a higher income gap, the distribution was disproportional. While this study may have not took into account the specific jobs of each couples, there still is evidence that with the policies supporting equal wages in genders there would be a positive effect on the division of household labor.

Throughout research, it is clear that the world is moving in the right direction but there are still many challenges women are still facing. The understanding of division of household labor is key to understanding the more complex issues that are prevalent in our society today but there are still topics that remain a question. What different patterns can we observe today about the distribution of household labor are there in the current world with lgbtq+ couples? How are disproportions of household labor different in fields that have a higher gender disparity such as fields in STEM? With further research in these topics can help make more policies that specifically target problems within certain fields and relationship compositions.

Igielnik, Ruth, (2021). A rising share of working parents in the U.S. say it’s been difficult to handle child care during the pandemic. Pew Research Center.

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/01/26/a-rising-share-of-working-parents-in-the-u-s-say-its-been-difficult-to-handle-child-care-during-the-pandemic/

Lively, ―Kathryn, & Suttie, J. S. J. (2019). How an unfair division of labor hurts your relationship. Greater Good. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_an_unfair_division_of_labor_hurts_your_relationship

REFERENCES

1.Greenstein, T. N. (2000). Economic Dependence, Gender, and the Division of Labor in the Home: A Replication and Extension. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 322–335. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1566742

2. Katherine Michelmore, & Sharon Sassler. (2016). Explaining the Gender Wage Gap in STEM: Does Field Sex Composition Matter? RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(4), 194–215 https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2016.2.4.07

3.Ross, C. E. (1987). The Division of Labor at Home. Social Forces, 65(3), 816–833. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578530