By Tyler Gordon and Jack Ginter

Overview

Traditionally, there has been a gendered division of labor, often characterized by stereotypical roles where men are expected to engage in paid work outside the home, while women are typically responsible for domestic tasks and caregiving. The gender dynamics of household division of labor often refers to the way in which tasks and responsibilities are divided between men and women within the household. As of recently, women have become increasingly engaged in labor market activities, with the most dramatic increase in mother’s employment outside the home. The two-earner household model has overtaken the traditional male breadwinner model in Europe as well as in the United States (Dribe, Stanford, & Buhler, 2009). Although there have been great advancements in employment rates and women’s time in paid work have increased, there are arguments that their time spent in unpaid work has not declined enough. There are many factors contributing to this. Research suggests that parenthood, education level, household income, and occupation all have dramatic impacts on the household division of labor. This blog post will take a deeper dive into this issue.

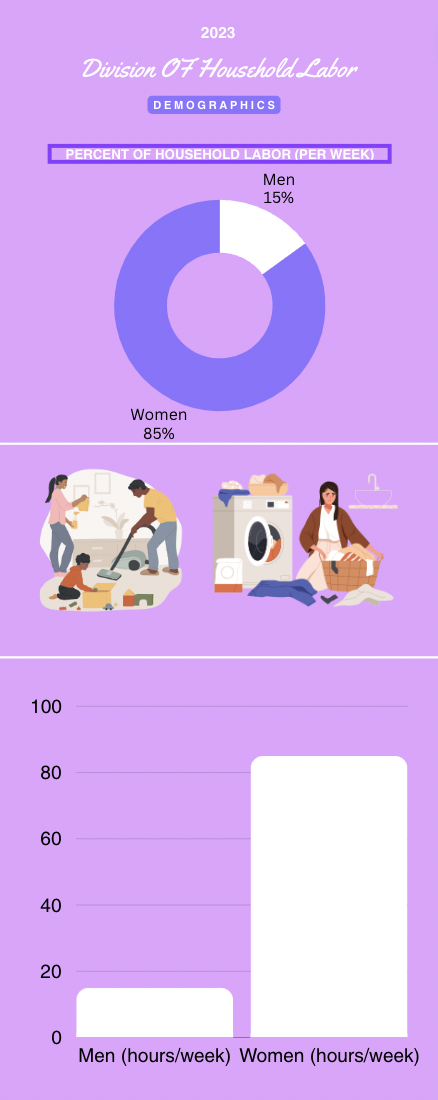

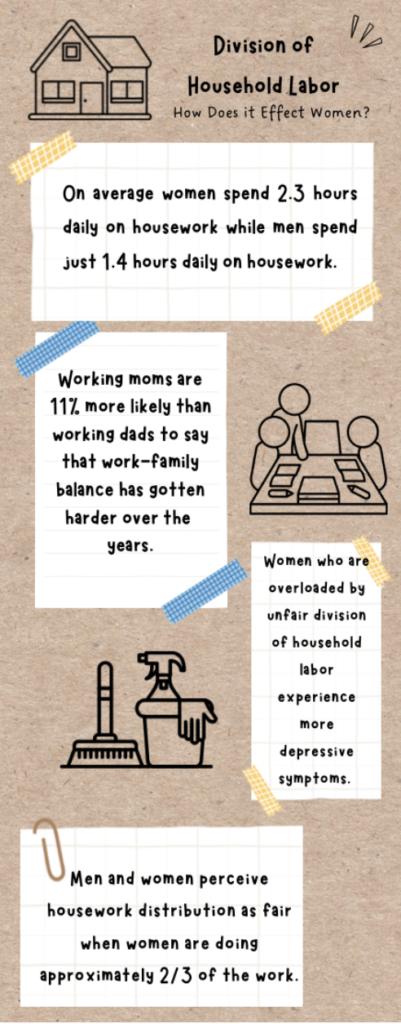

In almost every industrialized country, the household division of labor remains unbalanced and gender dependent. Women are still often left with the major responsibility for housework and childcare. Though the amount of time women invest in housework has declined in recent decades, the increase in time spent by men in household chores has only partially offset this reduction, except for highly educated professionals (Dribe, Stanford, & Buhler, 2009). Many studies suggest that women still perform the majority of housework.

Another significant factor of gender division of labor is parenthood. Following the birth of a first child, women invest more in domestic work and less in market work, and the market hours, earnings, and housework of men and women diverge (Musick,Bea, & Gonalons-Pons, 2020). Various factors contribute to this, such as societal expectations, traditional gender roles, and practical considerations. Employers also discriminate against mothers in hiring and wage-setting, viewing them as less competent and dependable, whereas fathers are seen as more responsible (Musick,Bea, & Gonalons-Pons, 2020).

The next factor is income level. Gender disparities vary across the income and wealth distributions. Today, women are now well represented in middle and upper-middle class occupations (e.gManagement and analyst jobs), there are still relatively few women in executive or other top leadership positions in major corporations, large law firms, or investment banking and hedge fund companies, where financial rewards can be exceptionally high (Yavorsky, Keister, Qian, & Thebaud). Higher-income households also typically have greater access to resources for domestic help, such as housekeepers, childcare, providers, or other support services. This can influence the division of labor by relieving both partners of some domestic responsibilities. Lower-income households often follow a more traditional division of labor, where one partner, often the one with the higher income or job stability, focuses on paid employment, while the other takes on a larger share of domestic responsibilities.

Policy Recommendations

As the studies cited point towards, women tend to show a propensity to seek part-time work schedules to cope with the incompatible demands of work and family (Webber & Williams, 2008). Women in the labor force feel immense pressure when juggling household responsibilities, especially when the family is dependent on her share of income. Oftentimes, childcare is so expensive today that working full-time and paying for services daily is a worse decision financially than working part-time and staying at home. One policy intervention that would alleviate this pressure while simultaneously combating the gendered division would be a cheap, state-subsidized child care program that every family has access to. Evidence on subsidized child care consistently shows positive effects on mothers’ labor force reentry and attachment following a birth (Musick, 2020). Another potential intervention would be paid to expand parental leave laws and implement dual-parent leave for both the man and woman after childbirth. Doing so would work to counter the standing gender stereotypes of childcare and household expectations.

Potential Consequences Without Intervention

If we maintain the same on the same track with the current gendered division of labor in society we should not expect the climate ever to get better. Besides the obvious reinforcement of gender role stereotypes that continue to happen, we need to keep in mind two threats posed to women, limited economic opportunities and career stagnation. With the current culture driving women out of the work force and into the home, women face barriers in accessing their respective professions or industries, limiting their economic opportunities and career advancement. Despite making up 47% of the labor force, women still are at a significant deficit to men due to factors like part-time work (Musick, 2020). This not only affects the mother, but also the overall economic welfare of the family. In addition, we stand to lose immense amounts of human capital and talent with women leaving the workforce. Career stagnation for women becomes a greater risk the longer women are out of their careers. With fewer women having the ability to achieve leadership positions, the strength of the labor market suffers as a whole.

Research Questions

- How does the availability and affordability of state-subsidized child care programs impact the division of labor within households, particularly in terms of women’s workforce participation, career advancement, and the reinforcement or challenge of traditional gender roles?

- What are the long-term effects of dual-parent leave policies on the gendered division of labor, considering factors such as changes in parental responsibilities, career trajectories, and perceptions of caregiving roles within households?

Infograph

References

Jill E Yavorsky, Lisa A Keister, Yue Qian, Sarah Thébaud, Separate Spheres: The Gender Division of Labor in the Financial Elite, Social Forces, Volume 102, Issue 2, December 2023, Pages 609–632, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soad061

Braun, M., Lewin-Epstein, N., Stier, H. and Baumgärtner, M.K. (2008), Perceived Equity in the Gendered Division of Household Labor. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70: 1145-1156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00556.x

Cohen, P. N. (2004). The Gender Division of Labor: “Keeping House” and Occupational Segregation in the United States. Gender & Society, 18(2), 239-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243203262037

Yavorsky, J.E., Kamp Dush, C.M. and Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J. (2015), The Production of Inequality: The Gender Division of Labor Across the Transition to Parenthood. Fam Relat, 77: 662-679. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12189

Musick, K., Bea, M. D., & Gonalons-Pons, P. (2020). His and Her Earnings Following Parenthood in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom. American Sociological Review, 85(4), 639-674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420934430

This imbalance has persisted across cultures, perpetuating the stereotype that housework is primarily a woman’s domain. However, it’s essential to recognize that these gender roles are not always present. These gender roles depend on multiple factors such as the education and occupation of both men and women, as the partner with no occupation might have more time spent in the household. This blog post dives into the correlation between the education level and career choice of men and the amount of domestic labor they participate in.

This imbalance has persisted across cultures, perpetuating the stereotype that housework is primarily a woman’s domain. However, it’s essential to recognize that these gender roles are not always present. These gender roles depend on multiple factors such as the education and occupation of both men and women, as the partner with no occupation might have more time spent in the household. This blog post dives into the correlation between the education level and career choice of men and the amount of domestic labor they participate in.