By Annika Dyczkowski and Libby Harris

Overview

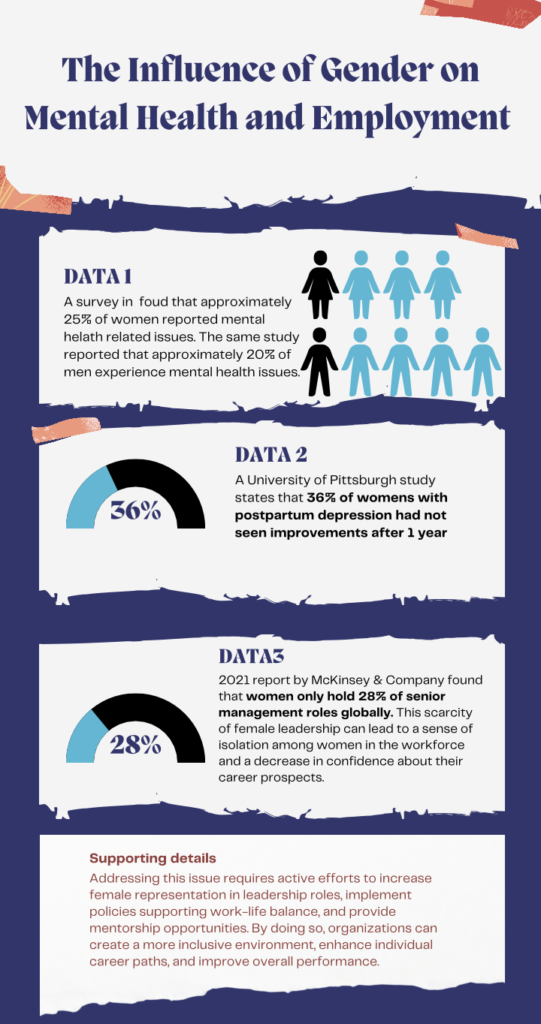

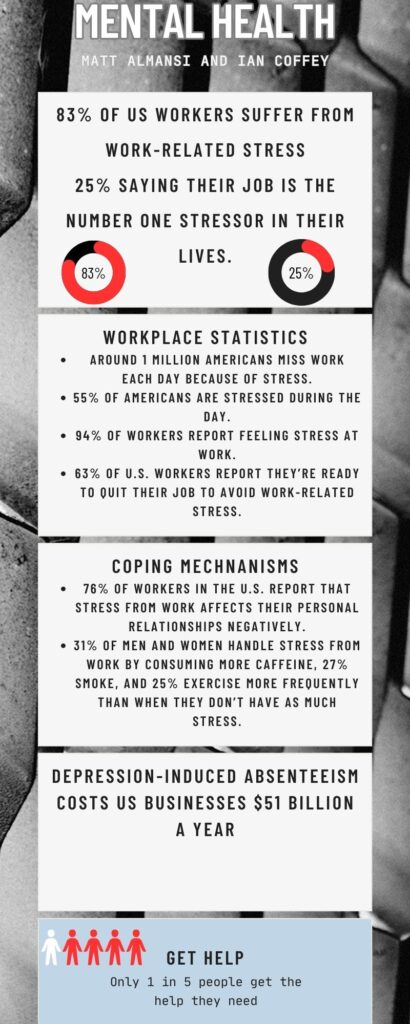

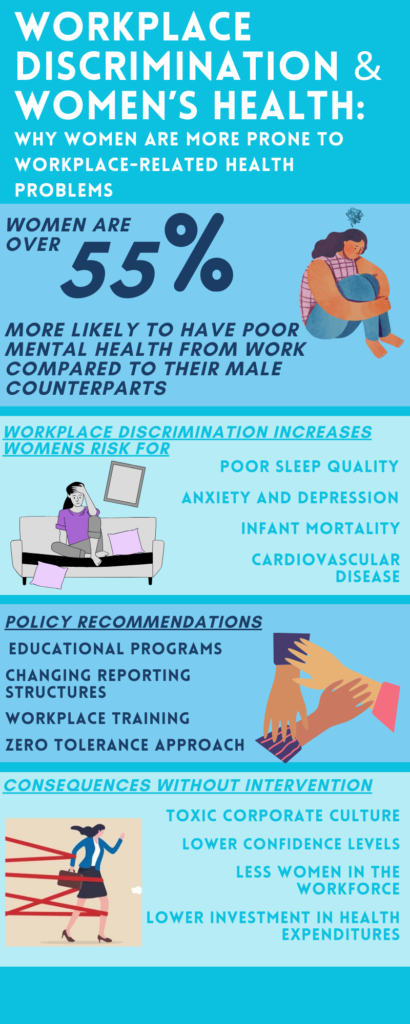

Women have faced discrimination throughout history in all walks of life. While it is more understood now in modern day how discrimination affects a woman’s financial freedom and independence, people are still failing to understand the dramatic effects that this discrimination can have on women’s health, both physical and mental. These adverse health consequences for women can manifest in numerous ways and in both the short-term and long-term. Some of these include diminished sleep quality, elevated C-reactive protein (CPR) levels which are linked to an increased risk for heart attacks, heightened anxiety and depression, and overall poor self-assessment. Should the woman be a mother, these health repercussions can adversely affect both the child and the broader family unit. Health problems, as such, can also lead to more of these women having to exit the labor force altogether, leading to less financial stability and the hindrance of women gaining leadership positions. Whether examining the intersectionality of discrimination in workplace experiences or a women’s living environment, there is an emphasis on the need for a comprehensive understanding that accounts for a multitude of factors. Research has shown that a woman’s experience with discrimination does have a direct link to resulting health impacts, regardless of the other factors outside of gender.

Policy Suggestions

It has become evident that discrimination adversely impacts the health of women and it is imperative to put an end to it. The allocation of funds, time, and effort in workplaces is of the utmost importance for resolving women’s continual discrimination in the workplace. Research presents that individuals, oftentimes, do not recognize some behaviors as harmful and reinforce an abusive or sexist workplace environment; these actions can be corrected formally through educational programs, changes in the organization of reporting structures, and mandatory workplace training. Proposed policies could incorporate a zero-tolerance approach, leading to the removal of individuals engaged in discriminatory practices. Additionally, policy could seek to provide a guidance or wellness staff member to assist both women and men if there are thoughts of anxiety and depression surrounding the workplace.

Consequences without Intervention

Without the implementation of the proposed policies, women will continue to suffer in both the short and long term. Women who remain in workplaces that perpetuate gender inequality will continue to undergo occupational discrimination that is harmful to their mental and physical wellbeing. The results of subsequent studies reveal that women who are targets of dissatisfactory workplace experiences are more aggrieved by their supervisors than their coworkers. This finding implies that women could have less respect for their supervisors, causing a burdening and toxic corporate culture due to a lack of workplace standards.

The result of poor health from workplace discrimination could also shift women’s attitudes towards their occupation, losing the perseverance and mental inclination to perform well at work, hindering women’s career progression in the long run; this lack of mental stability linked to corporate confidence could result in being overlooked for promotion decisions or important projects, or poor performance evaluations that they would not have been penalized for otherwise.

The poor treatment that women receive, consequently reflecting on their health, could also cause them to leave the workforce, feeling unmotivated and disinterested for the sake of their wellbeing. This consequence implies there would be less women with their own wage and disposable income, less women in the workforce, and less women with the ability to invest in their health, resulting in a troubling cycle of poor health.

If women continue to undergo antagonizing workplace culture, their health will continue to depreciate; this can be manifested as poor sleep conditions, confidence levels, and more disturbingly adverse effects like infant mortality or cardiovascular disease. Women’s inability to invest in their health due to poor workplace conditions can have detrimental effects on their mental and physical wellbeing, making policy implementation even more important to avoid these consequences.

Research Questions

- Are women who are unemployed as susceptible to the effects of discrimination as those who work full-time or part-time?

- Are women more vulnerable to enduring specifically mental health challenges arising from their occupational experiences?

- How does wage discrimination specifically impact the mental and physical well-being of women?

References

Andersson, Matthew A., and Catherine E. Harnois. “Higher Exposure, Lower Vulnerability? The Curious Case of Education, Gender Discrimination, and Women’s Health.” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 246, 2020, p. 112780, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112780.

Beatty Moody, Danielle L., et al. “Everyday Discrimination Prospectively Predicts Inflammation across 7‐years in Racially Diverse Midlife Women: Study of Women’s Health across the Nation.” Journal of Social Issues, vol. 70, no. 2, 2014, pp. 298–314, doi:10.1111/josi.12061.

Pennington, Andy, et al. “The health impacts of women’s low control in their living environment: A theory-based systematic review of observational studies in societies with profound gender discrimination.” Health & Place, vol. 51, 23 Feb. 2018, pp. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.02.001.

Phillips, Susan P. “Including Gender in Public Health Research.” Public Health Reports (1974-), vol. 126, 2011, pp. 16–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41639299.

Sojo, Victor E., et al. “Harmful workplace experiences and women’s occupational well-being.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 1, 2015, pp. 10–40, https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315599346.