In 1943, a dispute erupted between white West Hartford whites and federal housing officials over whether or not African Americans should be allowed to live in the World War II public housing tract called Oakwood Acres. Public housing tracts were created to house the many war workers and their families living in the Hartford area. The United States government funded these housing tracts, and therefore housing officials needed to abide by federal laws regarding occupancy. Federal Housing authorities eventually did require West Hartford to admit African Americans, however, town residents and leaders prevailed in controlling the rules used to maintain their virtually all-white community. Racist actions such as these were factors in shaping the demographic of West Hartford today.

Demand for housing was high throughout the United States during World War II. Across the nation, people moved into cities looking for jobs in wartime defense industries [1]. In 1940, President Roosevelt and the United States Congress established the United States Housing Authority (USHA) and authorized it to build public housing units [2] with the goal of providing housing for war workers.

In the 1940s there was an influx of war laborers, both White and African American, and their families into the greater Hartford area. These people worked in defense factories such as The Pratt and Whitney Machine Tool Plant [3]. As a result of this, housing options were limited in the Hartford area. In August of 1943, 8,000 new housing units were developed in Hartford and New Britain to accommodate the growing population [4]. The new options for housing were apartment style homes built under the Hartford Housing Association (HHA) and paid for with federal funding from the USHA. Compared to the rest of New England, Hartford successfully provided housing. According to a 1943 Hartford Courant report, “Connecticut has about half of all the government war housing constructed in New England. Half of the government housing in this state has been put up in the Hartford-New Britain area.”[5] With these impressive statistics, one may think that most of the need for housing in Hartford was met. However, families and African American war workers had the most difficult times finding homes.[6] To accommodate this, “400 housing units for white in-migrant families”[7] were being constructed, leaving only the African Americans without secure housing options. Berkley Cox, chairman of the HHA called this situation “satisfactory.”[8]

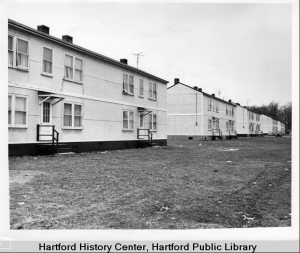

This photo was taken a decade after the debate

Image from CT History Online Flikr

Oakwood Acres

One unit developed under the HHA was the Oakwood Acres Housing Tract, on Oakwood Avenue in West Hartford. It spanned between St. Charles Street and Seymour Avenue. Oakwood Acres was described as new, simplistic, and affordable [9]. In 1943, only 14 out of the 300 apartments in the building were occupied [10], and many African Americans still had nowhere to live. The federal government’s plan was to use this space to provide housing for the African Americans in need of homes.

The Debate

Because the government funded Oakwood Acres, the unit needed to abide by federal law, which stated that officials could not legally reject African Americans applying for housing. West Hartford homeowners, living near oakwood Acres, were quoted in the Metropolitan News saying that they were “alarmed” and “horrified” at the idea of “Negroes” living in their neighborhood[11]. The Hartford Courant described the situation as an “infiltration” of African Americans[12]. This harsh, racist language described the overarching feelings of the neighborhood, “The general sentiment of these homeowners is: ‘We don’t want them here’.”[13] The Courant also portrayed the white homeowners as hardworking people who “invested their savings in their homes[14]” and did not deserve to live near African Americans.

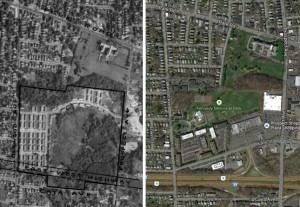

1951 image from UConn MAGIC aerial photography

2013 Image from Google Maps

Furiously, the homeowners wrote to Cox, of HHA, asking if the African Americans would be admitted to Oakwood Acres. Cox did not comment on the issue[15]. Because of this, the people of West Hartford sent petitions to their Senators Francis Maloney and John A Danaher, and Congressman William Milier.[16] Milier told the people that he would look into the issue of whether it was unlawful for Oakwood Acres to reject all African American applications for housing.[17]

The Outcome

The United States Housing Authority responded with an ultimatum. They stated that it was unlawful to exclude African Americans from Oakwood Acres based on their race. Local housing officials were advised that unless the race restrictions were lifted, the federal government would step in.[18] Under this decision, African Americans would be admitted if they applied for a unit. This angered the homeowners of West Hartford, prompting West Hartford housing officials to find a loophole. They decided to accept applications from only “Negroes with essential West Hartford industry jobs.”[19] This ruling was made knowing that there were only six African American families who fit this criterion, and they were not interested in living in Oakwood Acres.[20]

Ultimately, African Americans were technically allowed to live in Oakwood Acres. However, the local officials were able to find a way to limit the number of eligible African Americans so much that none actually did move into the tract. The white West Hartford housing officials and their supporters trumped the federal government.

In 1956, Oakwood Acres was demolished. It had become dilapidated and the people of West Hartford feared it made their neighborhood look like a “slum.” [21] By destroying the unit, West Hartford also erased this dark, racist part of their history.

Today, West Hartford is predominately a white community. One may argue that the demographic of West Hartford was shaped by racist, discriminatory actions begun by the housing committee and the people of West Hartford in the 1940s. In this case, the people of West Hartford were able to outwit the federal government to achieve their goal of preventing African Americans from living in Oakwood Acres. As more situations like this occurred over time, including the implementation of race restrictive covenants, the current demographic of West Hartford was shaped.

[1]Kristin, Szylvian. “The Federal Housing Program During World War II.” From Tenements to Taylor Homes. : 121.

[2]Kristin, Szylvian. “The Federal Housing Program During World War II.” From Tenements to Taylor Homes. : 123.

[3] “1877 Worker Visits New Tool Plant.” Hartford Courant, 10 29, 1941.

[4] “Housing Reaches 8000 mark in City and New Britain.” Hartford Courant, 08 14, 1943.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Negroes May Occupy Oakwood Acres to Solve Rental Lag.” The Metropolitan News, 09 03, 1943.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Housing Official Noncommittal On Racial Question.” Hartford Courant, 10 21, 1943.

[16] “Residents Ask Congressmen’s Aid on Negro Housing Threat.” Metropolitan News, 11 04, 1943.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Negros May Not Move Into Oakwood War Housing Tract.” Metropolitan News, 12 16, 1943.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Katherine Ellen Winterbottom, “Beneath the Veneer,” The Spectator [West Hartford Historical Society Newsletter] Autumn (1998): 1,10–14.

[22] Wilson, Tracey. “West Hartford in World War II.” . West Hartford Life, Last Modified 04 2002. Web. 7 Jan 2014.

Your essay does a fine job of situating this local housing debate within the national and regional contexts. Also, you made clear links at outset between this past issue and the present-day makeup of Hartford suburbs; this helps readers to understand why this piece of history is more than just an interesting factoid about WWII. Overall, the essay’s structure results in a logical flow of information and it is written in simple, easy-to-understand language with only a few grammatical issues in need of correction.

One passage that I particularly like is this: “To accommodate this, ‘400 housing units for white in-migrant families’ [7] were being constructed, leaving only the African Americans without secure housing options. Berkley Cox, chairman of the HHA called this situation “satisfactory.”[8]

The contrast between the clear need in the first sentence and the chairman’s matter-of-fact pronouncement of a satisfactory outcome in the second is powerful. Lastly, I am impressed by your choice to use Google maps to show where the now-vanished housing once sat. This is not only useful for readers, it also “reinscribes” an erased history back onto the landscape. The selected newspaper headline is strong and, in fact, I would place that as the lead image as it encapsulates the problem at the heart of this entry. Nicely done!