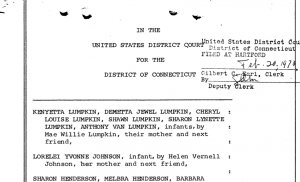

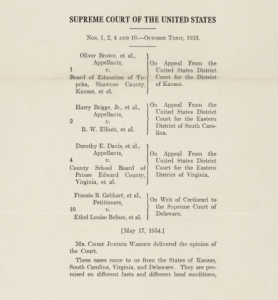

Sixteen years after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling outlawed racially segregated schools in Southern and border states, civil rights activists filed a similar lawsuit in the northern city of Hartford, Connecticut. The Brown v. Board of Education court case unanimously ruled (9-0) that, “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” on May 17th, 1954[1]. On February 20th, 1970, four minority Hartford parents challenged then Connecticut Governor, John Dempsey (1970-1971) in his ability to provide educational equity to all Hartford children by filing a similar lawsuit to that of Brown vs. Board of Education. Lumpkin v. Dempsey later recognized as Lumpkin vs. Meskill (Thomas J. Meskill 1971-1974) argued that certain Connecticut district laws functioned in such a way that they worked against the minority children of Hartford and ultimately denied them basic equal educational opportunities. The Lumpkin plaintiffs publicly challenged set school district boundaries between the city of Hartford and eight neighboring suburbs. The lawsuit challenged the efficiency of those district lines while raising important questions such as: why did certain towns have the ability to choose who they enrolled, and more importantly, why were Hartford schools not as academically successful as their neighboring suburban towns?

Legal Decisions leading to Lumpkin vs. Dempsey

Before the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954, the Board of Education abided by educational policies and regulations influenced by racial segregation. Under the jurisdiction of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, the notion of “separate but equal” was unanimously voted as unconstitutional in 1954.

Since its inception, the sole purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment has been to guarantee all American citizens equal protection of their laws. The plaintiffs in the Lumpkin v. Dempsey lawsuit based their case on the fact the government failed to provide equal opportunity to minority students residing in Hartford, therefore violating the Fourteenth amendment. Southern states utilized Jim Crow laws to create a distinct separation between racial differences. While Northern states, such as Connecticut did not directly mandate segregated schools in their state laws, the plaintiffs argued that laws practiced in the South were being indirectly practiced in the North as well. The Lumpkin plaintiffs, who happened to be of Hispanic and African American descent strongly believed that the educational system was de facto segregated by socioeconomic and ultimately racial means, whereas the plaintiffs in the Brown plaintiffs had factual evidence (established laws), which they argued to be inherently unequal.

The Fight For Equal Educational Opportunities in Hartford

Lumpkin v. Meskill placed the legitimacy and efficiency of Hartford’s Public School system into question. According to the initial complaint filed by the plaintiffs, Mae Willie Lumpkin, Helen Vernell Johnson, Barbara Henderson and Mary Diaz, certain Connecticut State laws function to segregate and create “racially imbalanced school districts”, and because they are not able to provide the plaintiffs and people of their class equal educational opportunities, are ultimately unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment[2]

The plaintiffs, all parents of minority children enrolled in Hartford public schools were identified as citizens of the United States, but belonging to similar ethnic groups: African American and Hispanic (particularly of the Puerto Rican ethnic groups). The plaintiff’s racial background became the driving force behind their lawsuit which claimed, that many schools in Hartford had an excess amount (90%) of minority students enrolled, therefore making it practically impossible to integrate the schools, which is why they sought help from higher echelons that would restructure the way minority groups were distributed within Hartford[3].

Mae Willie Lumpkin and the other three plaintiffs demanded that the court recognize the fact that certain laws violated rights, and most importantly, the ordering of the state to integrate suburban towns by erasing district lines and creating a regional school district in order to have statewide integration. Defendants Thomas J. Meskill and other members of the Board of Education countered their argument by stating that there were many discrepancies in the plaintiff’s complaints. These complaints included the misunderstanding of Constitutional laws, to vague accusations[4].

To counter the plaintiff’s claims, in the Reply Brief of Defendants, the defendants called the plaintiff’s claims weak and urged them to reconstruct the foundation of their argument. “However, they [plaintiffs] are strangely reticent about stating with some specificity just what educational opportunities the defendants are denying to them and in what way such denial is being accomplished by the defendant State officials.[5]” The defendants based their counter argument on the fact that, the state oversees district activities such as: allocation of resources for a fiscal year, implement educational interests for the school year, but does not control site selection, enrollment or construction of the school. The court brief reiterates the fact that “Neither state law nor the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution mandate equal educational achievement for every child attending a public school,[6]” thus making the Lumpkin argument invalid.

Dissenting Opinions that Lead to Demise of Lumpkin Case

As Lumpkin v. Meskill gained regional attention, dissenting opinions arose from parents living in the surrounding suburban neighborhoods. Various periodicals of the time tracked the opinions of residents in the neighboring towns such as Bloomfield and

Windsor. “The Bloomfield School board, one of the eight suburban boards named in the suit, is the only one to support the Lumpkin side of the issue requiring total integration”[7] wrote journalist Bill Grava in a Hartford Courant article published in 1974. Parents of students enrolled in Bloomfield schools were not pleased with the unanimous decision in a Parent-Teacher Association meeting to support the plaintiffs of Lumpkin v. Meskill. Another article published by James Ross, states, “‘I’m so burned up’ one parent said, ‘If this thing works, are they going to throw kids out like cattle? Will they divide kids up by color like a rainbow?’…. The parent accused the board [Parent-Teacher Association] of not wanting to fight.[8]”

Brown vs. Board of Education asserted that it was unconstitutional to racially segregate schools. Nearly two decades later, a four to five decision in Detroit resulted in the dissemination of a regionalization plan that would integrate schools involving nearly 800,000 students [9]. Milliken v. Bradley (1974) made it clear that because suburban towns had no direct involvement with creating a segregated environment, they were not obliged to help desegregate the districts in any way. The Milliken ruling played a critical role in the influence of the decision to dismiss the Lumpkin case because the decision clearly stated that suburban towns would not be held responsible for integrating cities. The Lumpkin plaintiffs specifically asked for the cooperation of the eight surrounding suburban towns in the initial lawsuit, and because this ruling made it constitutionally viable to refuse participation that is what many school districts chose to do.

A decade after both rulings, Sheff v. O’Neill surfaced, arguing a similar point to that of the Lumpkin case. The determining factor of the success of Sheff was the critical decision to take Sheff to the Connecticut Superior Court, versus Federal district court as done by Lumpkin plaintiffs. The complaint filed on April 26th, 1989 argued that the state of Connecticut allowed school districts to operate under racially, and socioeconomically segregated conditions ultimately allowing the state to create racially isolated residential communities such as those found in Hartford. In her book, The Children in Room E4, author Susan Eaton claims that there are parallels between the Lumpkin and Sheff cases, the earlier becoming the impetus for the latter to file in a higher level court, rather than Federal district court[10].

Ultimately, the Lumpkin case was left dismissed by the Federal District courts. After 1980, the plaintiffs, who worked endlessly to prove that those controlling the Board of Education caused the disparities in the public educational system were unheard of, and to this date there is no real updates of Mae Willie Lumpkin, or her childrens’ whereabouts. Although the Lumpkin case did not gain nation-wide recognition, it became the impetus for other big lawsuits such as the 1989 Sheff case, whose results have affected and will continue to affect children in Connecticut and potentially children across the nation for years to come. The Lumpkin case was the first of it’s kind; the plaintiffs being brave as parents of minority children to challenge those in power regardless of the socioeconomic and ethnic boundaries to fight for equal rights.

Work Cited

- Collier, Christopher. Connecticut Public Schools: A History, 1650-2000. Orange: Clearwater Press, c2009.

- Eaton, Susan. The Children in Room E4. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, N.C., 2007.

- Grava, Bill. “Smith Predicts No Regional School Board: Bloomfield.” The Hartford Courant (1923-1987). February 20, 1974.http://search.proquest.com/hnphartfordcourant/docview/552135542/abstract/140FFE468547E9ED9BF/1?accountid=14405.

- Ross, James. “Town Viewed as Now Meeting Desegregation Suit Objections: Bloomfield.” The Hartford Courant (1923-1987). April 26, 1974.http://search.proquest.com/hnphartfordcourant/docview/552141713/abstract/140FFD210DA46836B93/7?accountid=14405.

- “Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka – 347 U.S. 483 (1954).” Justia US Supreme Court Center. Accessed October 8, 2013.https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/347/483/case.html.

- “Lumpkin Reply Brief Court File” United States District Court, District of Connecticut; Filed in New Haven on August 25th, 1972. Attorney Robert K. Killian. Accessed via DropBox October 8,2013 https://www.dropbox.com/sh/pktjiisx2zhi9bz/erOj3QfPzP/Lumpkin_19720825%20D%20Reply%20Brief%20CourtFile.PDF.

- “Lumpkin Plaintiff Complaint” United States District Court, District of Connecticut; Filed at Hartford on February 20th, 1970. Attorneys Raymond B. Marcin, and Douglas M Crockett. Accessed October 8,2013 via DropBox.

[1] “Brown V. Board of Education of Topeka – 347 U.S. 483 (1954).”

[2] Attn. Marcin, Attn. Crocket, Lumpkin Plaintiff Complaint, 6.

[3] Attn. Marcin, Attn. Crocket, Lumpkin Plaintiff Complaint, 5.

[4] Attn. Robert K. Killian, Lumpkin Reply Brief Court File, 16.

[5] Attn. Robert K. Killian, Lumpkin Reply Brief Court File, 23.

[6] Attn. Robert K. Killian, Lumpkin Reply Brief Court File, 24.

[7] Grava, Bill. “Smith Predicts No Regional School Board: Bloomfield.” The Hartford Courant (1923-1987). February 20, 1974.

[8] Ross, James. “Town Viewed as Now Meeting Desegregation Suit Objections: Bloomfield.” The Hartford Courant (1923-1987). April 26, 1974.

[9] Collier, Connecticut’s Public Schools: A History: 1650-2000, 634.

[10] Eaton, Children of Room E4, 79.

The essay’s opening clearly sets the case within the context of the better-known Brown v. Board of Education. Likewise, you made effective use of the Detroit case to explain why Lumpkin ultimately faltered. Nicely done! Also, effective is the manner in which you use questions raised by the lawsuit as the transition to your explanation of the case. This is an effective tactic that makes readers curious to know more while also focusing their attention on the important issues at stake.

In several places sentence structure obscures your meaning. For example: “Southern states utilized Jim Crow laws to create a distinct separation between racial differences.” This phrasing supposes that the laws enforced separation of “differences” vs. a separation of people. I suspect you wanted to emphasize that such laws segregated African Americans from full and equal participation in white-dominated areas based on a biased presumption of not only of racial difference but an assertion of black inferiority. Another example is: “Defendants Thomas J. Meskill and other members of the Board of Education countered their argument by stating that there were many discrepancies in the plaintiff’s complaints. These complaints included the misunderstanding of Constitutional laws, to vague accusations.” Here I think you mean that the defendants accused the plaintiffs of vague accusations and misunderstanding Constitutional law. The problem arises because the term “complaints” appears once with regard to the plaintiff and again in the next sentence to refer to the defendants’ counterarguments. Also, shifts between past and present tenses detract from the writing

One point that needs clarification is the matter of how “The Lumpkin case was the first of it’s [NO APOSTROPHE HERE] kind.” At the outset, it is noted as being like Brown, so was it the first of its kind in a northern state? But then Detroit provides a precedent; so was its first of its kind in New England or, perhaps, in Connecticut? Overall, this essay does a strong job of situating this case within the broader national context. This entry is also important because it enhances reader understanding of the better know Sheff case.

A correction to my own prose (and proof that we should all proof read before hitting submit!

I suspect you wanted to emphasize that such laws segregated African Americans from full and equal participation in white-dominated areas. Such laws were based not only on a biased presumption of racial difference but on the assertion of black inferiority/white superiority as well.