Imagine you are a Hartford parent with a school age child. You have applied to the Open Choice program in Hartford so that your child might attend a school in the neighboring suburbs. Your child would be able to attend a great suburban school with a quality education and with students who most likely score higher on high stakes tests such as the Connecticut Mastery Test (CMT) or the Connecticut Academic Performance Tests (CAPTs) than Hartford public school students. The graduation rates are much higher in suburban towns. In the Hartford district, the graduation rate was at a low 79.6% in 20081 ; while just outside its borders, West Hartford had an outstanding graduation rate of 94.8%2. Of the Hartford population over 25 years of age, only 67.1% of the population has a high school degree and 13.6% of its population has a bachelor’s degree or higher as of 20103. The reality is that many students in Hartford don’t finish high school or continue their education after high school, but you insist on obtaining the best education for your child which is outside of Hartford’s borders with the exception of a few Hartford schools. You want your child to get a great education and graduate from high school and some day college. You have formed such high hopes for your child’s future, but only to find out that your child’s application to the Open Choice program has been denied. Your child did not get a seat in a suburban school. What do you do now? This is the reality for many Hartford families who hope their children can receive the best education which is often outside of the Hartford borders, and it was the hopes and dreams of Hartford families that led to the Sheff v. O’Neill case that began a process of providing at least some of Hartford’s minority students with a quality education.

In 1989, several Hartford families filed against the state of Connecticut because their children were racially isolated and were not receiving a quality education. The court ruling on the Sheff v. O’Neill case stated that the state was in violation of a “substantial equal education.” Although schools were not segregated by any law, it was considered defacto segregation and therefore intentional. Since the initial court ruling, the Sheff plaintiffs continue to file motions because Hartford minority students are still racially isolated in schools. The latest Sheff ruling states that 41% of Hartford minority public school students must be in reduced isolated settings 4 . With the progress made in developing magnet schools and sending students to suburban schools, the goal still has not been met. The Sheff ruling has continued to insist on making participation of suburban districts voluntary, but is voluntary enough? I would argue that those involved in the Sheff case must move beyond voluntary participation of districts and push for mandatory participation of suburban districts in the Hartford area by requiring that the district take in a certain percentage of students and while still maintaining voluntary participation of the families in the area.

Remedies to reduce the isolation of Hartford public school students have insisted on voluntary participation of districts. The surrounding districts decide whether or not they want to receive Hartford minority students and how many they wish to take in. In the first and second stipulation, the court insisted that districts should participate voluntarily. The stipulation called for the participation of interdistrict magnet schools, state technical schools, charter schools, vocational schools and the Open Choice program in this attempt at desegregating. The first Sheff stipulation specified that by 2007, 30% of Hartford’s minority public schools students would be in schools that were not racially isolated. According to a report by Erica Franskenberg, 13.9% of Hartford minority students were in reduced isolated school settings by 2007 5. The first Sheff remedy was a failure. Now Phase II of the Sheff case requires that 41% of Hartford’s minority public school students be in reduced racially isolated schools by October 2012. As of October 2011, data collected by CREC revealed that only 32.16% of Hartford’s minority public schools students were in racially reduced isolated settings6. When the Cities, Suburbs, and Schools class had a conversation with Phil Tegeler, a lawyer in the Sheff v. O’Neill case, Phil said,

“Yes, I think it [the goal of 41% of Hartford students in reduced racially isolated settings by 2013] will definitely take longer. I don’t think it’s an unrealistic goal. I think there were some problems along the way getting there. I think the state could have done a few things differently7.

Phil along with others involved with the case and the desegregation efforts are well aware that the goal will not be met by 2013. He believes that the state could have met the goal if they had only done things differently.

The attempt at desegregating students in the Hartford area failed due to the stipulation’s insistence on the voluntary participation of Hartford area suburban districts. The stipulations did not require that districts participate in desegregating schools. Phil Tegeler said,

“From the perspective of the Sheff Coalition and lawyers also, there is nothing voluntary about Sheff v. O’Neill. It’s a court mandate. It’s a court order agreement with very specific requirements. When we use the term voluntary, we’re talking about parental choice. Parents are not forced to send their kids to a magnet school. Hartford parents are not forced to bus their kids to a suburban school. It’s a completely voluntary…That’s what we mean by voluntary. There are also some aspects of the order which are a little too voluntary in a bad way which is that towns are still not required to take a certain number of kids, and that’s not what we mean by voluntary. We think that’s a defect of the agreement8.”

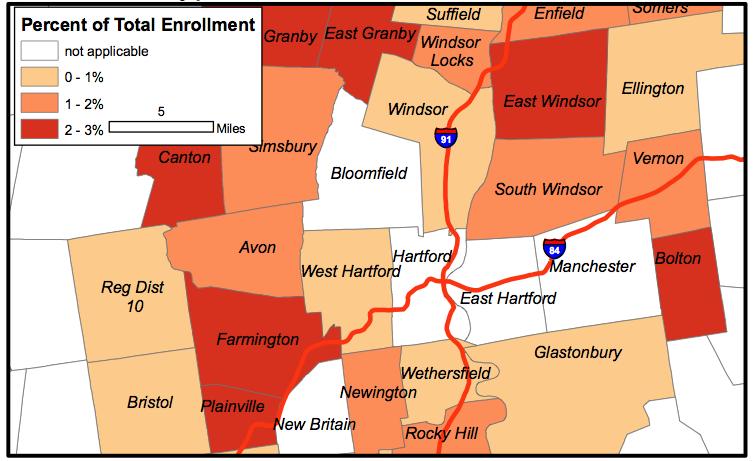

According to Tegeler, the remedies of the Sheff v. O’Neill case are not voluntary. The state is responsible and required to desegregate schools. He also emphasized the importance of parental choice in participating in desegregation efforts, but that the real issue of current Sheff remedies is that suburban districts have not been required to take in Hartford minority students. The Hartford area suburban districts that did participate had less than 3% Hartford minority students represented in their total enrollment (see image below).

The report by Frankenberg showed that suburban schools had many available seats that could be filled while still remaining below capacity. Based on her research, she estimated that there were 12,018 available seats in suburban districts in the 2005-6 school year, but the suburban districts had only taken in 1,125 Hartford minority students9 (see table below).

Since the participation of suburban districts has remained voluntary, many have pushed for incentives in order to get suburban schools to participate in desegregating the Hartford area. In January of this year, 2011, a bill was proposed to increase the financial incentives for participation in Open Choice. The proposed bill No.5665 by Republican Schofield states that Connecticut should halt the construction of magnet schools and instead give the money to receiving districts. The bill proposes that the state award $2,000, $4,000, or $6,000 per out of district student to districts with less than 2%, 2-2.99%, or 3% of out of district students in the total enrollment and that the Commissioner of Education be given the authority to place out of district students in nearby district schools if there are spaces available 10. The proposed bill asks that the state encourage participation of suburban districts by offering more money to schools to offset expenses such as books or transportation for the out of district students, and if the financial incentives are not enough then the authority should be given to place students in suburban classrooms. If the Hartford area schools are to be segregated then the state must move away from the “voluntariness” of participation of suburban districts in desegregation remedies.

Past Sheff remedies have attempted to desegregate schools by making participation of Hartford’s neighboring districts voluntary. Sheff remedies have emphasized that participation is voluntary for districts and families. Yet, the voluntary participation of suburban districts has been the downfall of efforts to desegregate schools. The majority of Hartford students in racially reduced isolated settings are in newly created magnet schools, and it would be more cost effective for the state to have Hartford students go to already existing schools in the suburbs. There are some districts that are not participating in desegregation efforts and the districts that are participating are enrolling less than 3% of Hartford students out of their total enrollment. The Open Choice program has attempted to place Hartford students in suburban schools, but their efforts are not enough if they do not have the support of the state which has the authority to make suburban district participation mandatory. There are thousands of empty seats in suburban schools waiting to be filled, and the state must take action to fill these seats with Hartford students. If any progress is to be made, the Phase III stipulation must make participation of suburban districts mandatory while maintaining the participation of families voluntary.

- State of Connecticut, “State Department of Education CEDAR: Graduation Rates.” Accessed December 11, 2011. http://sdeportal.ct.gov/Cedar/WEB/ct_report/GraduationDTViewer.aspx

- IBID

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Hartford (city) Quickfacts.” Last modified October 18, 2011. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/09/0937000.html

- Sheff v O’Neill, Stipulation and Proposed Order, Connecticut Superior Court, April 4, 2008. http://www.sheffmovement.org/pdf/SheffPhaseIIStipandOrder.pdf

- Franskenberg, Erica, “Project Choice Campaign: Improving and Expanding Hartford’s Project Choice Program,” Poverty and Race Research Action Council, September, 2007, http://www.prrac.org/pdf/ProjectChoiceCampaignFinalReport.pdf

- “Summary of Hartford Resident Minority Students in Reduced Isolation Settings,” November 16, 2011, http://www.sheffmovement.org/pdf/Reduced_Isolation_Summary.pdf

- Interview with Phil Tegeler, November 9, 2011

- IBID

- Franskenberg, Erica, “Project Choice Campaign: Improving and Expanding Hartford’s Project Choice Program,” Poverty and Race Research Action Council, September, 2007, http://www.prrac.org/pdf/ProjectChoiceCampaignFinalReport.pdf

- State of Connecticut General Assembly, “Proposed Bill No. 5665: AN ACT CONCERNING EXTENDING THE MORATORIUM ON NEW MAGNET SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION AND FINANCIAL INCENTIVES FOR PARTICIPATION IN THE OPEN CHOICE PROGRAM.” January 2011. http://www.cga.ct.gov/2011/TOB/H/2011HB-05665-R00-HB.htm