Photo Credit: Fionnuala Darby Hudgens

In an old Catholic school building, at the end of Blue Hills Avenue in the North End of Hartford, sits Jumoke Academy. The yard surrounding this pre-kindergarten through eighth grade charter school is neat, but without frills. Only a single maroon awning identifies the school by name. A small play structure is squeezed onto the property, which spreads only about a hundred feet from the building. Judging by the old, plain building, high academic success and remarkable student growth might not be the first expectations that come to mind. But on the other side of the walls, a racially and economically isolated urban minority student body is steadily undermining the Connecticut achievement gap. As journalist Stan Simpson explains,

“Remarkable progress in educating poor, urban, ethnic minorities in a state with the widest achievement gap in America makes you take notice.”1

Click to read full story.

Click to read full story.

Freely available at: @hartfordcourant. Hartford, CT: Hartford Courant, 2011, JPEG, Twitter feed, accessed December 2, 2011, http://yfrog.com/h8cxzebtj.

Jumoke Academy has been consistently recognized by ConnCAN as a school success story. In 2011, Jumoke was ranked #5 in the state for Middle School Performance Gains and #3 for African-American school performance.2 Yet according to one of the state’s primary education benchmarks—racial integration—Jumoke is failing. The 1996 decision by the Connecticut Supreme Court in Sheff v. O’Neill established that public schools in Hartford were racially, ethnically, and economically isolated, providing the legal ground for Sheff supporters and educational activists to initiate desegregation efforts in Connecticut education. However, the decision did not specify strategies outlining exactly how to effectively meet the desegregation mandate. As a result of unclear remedies and a tangled web of interdistrict magnet, charter, and traditional public schools, the system of public education in Connecticut has become difficult to navigate. Uncoordinated school choice options, goals, and measures of success have created an atmosphere in which student achievement can easily be overlooked in the quest for racial equality.3 Jumoke Academy, a racially isolated charter school, does not fit into the ideals of the Sheff movement. The student body, while high achieving, is 99.5% minority.4 The extraordinary success achieved at Jumoke Academy highlights one of the most significant shortcomings of the Sheff-based reforms in Hartford schools. By treating desegregation as an end instead of a means, the Sheff v. O’Neill mandates may de-emphasize student achievement, remove vital resources from the Hartford school district, and dismiss the sense of community found in neighborhood schools.

Jumoke Academy was once part of a long list of failing public schools in Hartford, and it remained that way for almost ten years. To stave off closure, Jumoke Academy began what school CEO Michael Sharpe identified as “addressing the barriers to learning of our students.” The majority of Jumoke Academy’s students lived in poverty, forcing the school administration to focus on the basic needs of the children that, until fulfilled, would interfere with students’ focusing on their schoolwork.5 Sharpe discussed how the school started with the basics to set a foundation for success on the Stan Simpson show, a clip of which can be seen below.

Stan Simpson: Urban School Turnaround Pt 2 | 10/23. YouTube Video, 7:20 minutes. Hartford, CT: CT Now, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SdHQtdpGWgg.

Administrators at Jumoke Academy responded to the high needs of their students by offering things like free breakfast and lunch, after-school enrichment programs, and Saturday sessions. By dealing head on with the needs of its students, Jumoke Academy began a steady rise and is now a top performing school within the Hartford district and in the state of Connecticut. The problem for the State in regards to Jumoke Academy is the demographics of the student body. Jumoke Academy does not contribute to the State’s goal of meeting Sheff objectives, making it difficult to evaluate the extent of its success.

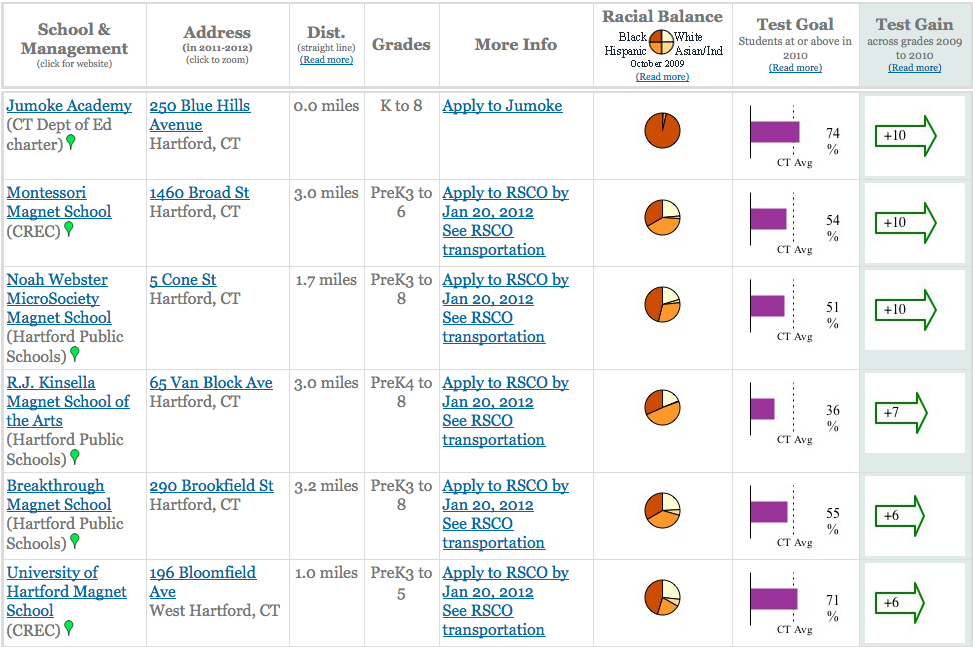

Sheff supporters praise the interdistrict magnet schools that have been built or expanded in Hartford since the original 1996 decision. However, in terms of student performance, Jumoke Academy is competitive with even the best magnet schools. Below is a screenshot from the SmartChoices website, with a comparison of Jumoke Academy and several magnet schools. Even though Jumoke Academy clearly “fails” in the racial balance category, it is competitive with other magnet schools in the district in terms of test scores, and in some cases it actually out-performs them.

SmartChoices Comparison: Jumoke Academy with Five Interdistrict Magnet Schools

Click to see larger image.

Click to see larger image.

Cities, Suburbs, and Schools Project. “Smart Choices.” Hartford, CT: Trinity College, 2011. http://www.smartchoices.trincoll.edu.

In addition to evidence that racially isolated schools can still be high-performing, the appropriateness of Sheff goals are also questionable in light of the fact that desegregation does not automatically result in higher student performance. The graphs below show the percentage of students at Jumoke Academy and IB Global Magnet achieving proficiency in reading and mathematics on the Connecticut Mastery Test. Despite its full compliance with Sheff desegregation mandates, IB Global Magnet is underperforming when compared to Jumoke Academy.

CMT Score Comparison in Reading and Math: Jumoke Academy with IB Global Magnet

Click to see larger image.

Click to see larger image.

“Jumoke Academy and IB Global Magnet Performance Overview.” Hartford, CT: Connecticut Education Data and Research, 2011. http://sdeportal.ct.gov.

Students at Jumoke Academy might be missing some opportunities that can only be offered in integrated schools, but a high quality education is not one of them.

Beyond the fact that Jumoke Academy out-performs some of the magnet schools in Hartford, administrators have caught on to other limitations of Sheff remedies. In many ways, it is not in the long-term interest of the city of Hartford to have its students bused off to suburban schools. In practical terms, the program places a significant burden on Hartford students who have to spend extra time traveling to and from school each day, and who might not get the chance to participate in extracurricular activities because of transportation limitations.6

Click to read full story.

Click to read full story.

Rabe Thomas, Jacqueline. “Increased reimbursements pay off in getting state closer to desegregating Hartford schools.” Hartford Courant, November 24, 2011. http://www.ctmirror.org/story/14609/increased-reimbursements-pay-getting-state-closer-desegregating-hartford-schools.

A drain on the financial resources of Hartford Public Schools is also occurring as a result of Sheff measures. As funding for new magnet school construction dries up, Sheff proponents have switched emphasis to Project Choice, a program that transfers Hartford students to suburban schools. Reimbursement for suburban schools that participate in Project Choice was recently increased from $2500 to $6000 per student in order to entice suburban districts to expand the transfer program.7 Compensating suburban schools for transfer students means that that money is unavailable to city schools, which arguably require the funds more because they have more high-needs students. Former Superintendent Stephen Adamowski believed that expanding Project Choice by 3500 students would mean that six or seven Hartford schools would have to close and that 700 employees would lose their jobs.8 Improving the education quality of Hartford students should not be a zero-sum game, in which one side only wins at the expense of the other. If integration goals are met only by decreasing the resources of students and faculty outside the system, even when those schools have demonstrated high student performance, then it seems as if the fundamental goal of school quality and student achievement is being ignored.

In the 2007 Sheff negotiations, Representative Doug McCrory raised concerns about the direction and focus of the Sheff remedies:

We focus a lot on the desegregation part, but one part we refuse to talk about is the academic achievement of children…I don’t want anyone to think that I’m not a supporter of Sheff…[But] if we can develop some [charter] schools in the Hartford region [that are] 95 percent minority, and those kids are kicking butt on CMTs and the academic levels are high and they’re going to college, I think our children should be in those schools.9

If high-performing schools exist within the city limits, then school administrators should be advertising and promoting those schools. This should not be interpreted as a challenge to Sheff remedies or goals. The Sheff mandate applies to the entire state of Connecticut, so Hartford should not have to bear the burden by emptying its schools and sending all of its money to the suburbs if it can offer effective alternatives.

In more abstract terms, there is also much to be said for being able to attend a quality school in one’s own neighborhood, as opposed to having to commute to a quality school in another town. Students should be able to go to school with their neighbors and to have easy access to after-school activities and the additional resources a school can provide. In defending his reform efforts, Adamowski noted, “What they really want is what every parent in America wants, which is a good school in their own neighborhood.”10 Unlike interdistrict magnet and Project Choice schools, Jumoke Academy serves the community it is located in. It is therefore better positioned to understand and address the unique needs of its students. Pedro Noguera has argued that this sense of community is essential in the education of students in high-needs settings. “Rather than being regarded as hopelessly unfixable, urban public schools, particularly those that serve poor children, must be seen for what they are: the most enduring remnant of the social safety net for poor children in the United States.”11 The success of the students at Jumoke Academy depends on the close attention the school gives to their circumstances. This kind of support might not be available at distant suburban schools, where only a small percentage of the student body is characterized as a high-needs population. Furthermore, neighborhood schools can offer services and support to non-student residents of the area. Allowing local schools to close in the name of integration could be severely detrimental to the entire Hartford community.

Integration is a noble goal, and the Sheff lawyers clearly established that racially isolated schools have inherent challenges. The problem with using Sheff goals to assess a school like Jumoke Academy, however, is that desegregation is still far from being the reality of Hartford schools. The state has invested millions of dollars in Sheff remedies since 1996, but the chances of a student getting to attend an integrated magnet school are still only between five and ten percent.12

Odds of Acceptance to Magnet Schools for 2010-2011 School Year

Click to see larger image.

Click to see larger image.

“Hartford-Resident Student RSCO 2010-2011 Magnet School Placement Odds.” Hartford, CT: The CT Mirror, 2011, PDF. http://www.ctmirror.org/sites/default/files/documents/wait%20list.pdf.

As of October 2011, only 32 percent of Hartford students were attending integrated schools.13

Click to read full story.

Click to read full story.

Rabe Thomas, Jacqueline. “With deadline looming, state still far from finish line on integrating Hartford schools.” Hartford Courant, November 21, 2011. http://www.ctmirror.org/story/14578/deadline-looming-state-still-far-finish-line-integrating-hartford-schools.

This means that, almost twelve years after the Sheff lawsuit, approximately 14,700 Hartford minority students remain in isolated school settings. These students will be left behind by any system that uses desegregation as its only measure of success. Policy makers must address the needs of these students even if that means accepting racial isolation for the time being in order to better address the specific needs of the students these isolated schools serve.

An argument could be made that competition for valuable resources is exactly what Hartford schools need. Project Choice and interdistrict magnet schools create competition that pressures neighborhood schools to improve performance in order to retain students and funding. Greater school accountability is one benefit that has come out of increasing school choice efforts to promote desegregation, and this should increase academic standards across the district. In fact, competition is likely one of the reasons for Jumoke Academy’s recent success. Amid whispers of shutting the school down for chronic low performance, officials like Mr. Sharpe changed the school’s structure and focused intently on increasing student performance.

There is great value in school choice and accountability, but the competition should not be so intense that struggling schools do not receive the support they need to improve. The Sheff ideals and remedies should be included in a broader system of school reform, but that system should be comprehensive and include a variety of goals for school quality and academic achievement. While desegregation is undoubtedly a need in Connecticut’s schools, it is not the only characteristic that should be measured or pursued. At least until integration programs have been significantly expanded, resources should be devoted to finding the best way to educate the children left behind by the integration movement. Expanding Sheff remedies at the expense of funding for neighborhood schools will mean that the majority of Hartford’s students will receive a lower quality education, and high-performing schools like Jumoke Academy might lose the financial support they need to continue making strides towards closing the achievement gap.

Integration is a means to an end, not an end itself. The ultimate goal of any education policy should be improving students’ academic achievement, and this goal should not be lost in the battle between competing reform agendas. Jumoke Academy, and many other Hartford Public Schools, has made incredible strides. Students in Jumoke Academy are closing the achievement gap and matching, if not outperforming, their peers in racially balanced settings, and this is what policymakers should be attempting to reproduce. Bruce Douglas, executive director of the Capitol Region Education Council in charge of Hartford’s interdistrict magnet schools, captured this sentiment perfectly: “My attitude is education is so important, I don’t care what school they go to. If it’s a good school, go there.”14

The reform of Hartford schools is an ongoing effort. We encourage you to become part of the debate by contacting policy makers with your comments about city schools, school choice, and desegregation:

Connecticut General Assembly Education Committee

Connecticut State Commissioner of Education

Jumoke Academy

About the Authors:

Fionnuala Darby Hudgens is an Education Studies major at Trinity College in Hartford, CT. Her academic interests lie in communicating a greater understanding of Connecticut’s achievement gap and the overall inequality in the American public education system.

Mary Morr is a senior Public Policy major at Trinity College, concentrating in education policy. She plans to pursue a Master of Social Work and is interested in the intersection of public education and the unique needs of disadvantaged children.

Footnotes:

- Stan Simpson, “Charter Lesson: High Goals, Accountability Turn Schools Around,” Hartford Courant, October 28, 2011, http://articles.courant.com/2011-10-28/news/hc-op-simpson-schools-charter-1028-20111028_1_achievement-gap-urban-schools-amistad-academy. ↩

- “2011 Top 10 Rankings,” Hartford, CT: ConnCAN, 2011, http://www.conncan.org/sites/default/files/conncan_2011_top_10_lists_final.pdf. ↩

- Jack Dougherty, Jesse Wanzer, and Christina Ramsay, “Sheff v. O’Neill: Weak Desegregation Remedies and Strong Disincentives in Connecticut, 1996-2008,” in From the Courtroom to the Classroom: The Shifting Landscape of School Desegregation, edited by Claire E. Smrekar and Ellen B. Goldring, 103-127, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2009. ↩

- Jumoke Academy Strategic School Profile 2009-2010,” Hartford, CT: State Department of Education, 2010, www.sde.ct.gov. ↩

- Stan Simpson: Urban School Turnaround Pt 1 | 10/23. YouTube Video, 8:52 minutes. Hartford, CT: CT Now, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQ6eihlBWl8. ↩

- Jacqueline Rabe Thomas, “Increased reimbursements pay off in getting state closer to desegregating Hartford schools,” The CT Mirror, November 24, 2011, http://www.ctmirror.org/story/14609/increased-reimbursements-pay-getting-state-closer-desegregating-hartford-schools. ↩

- Rabe Thomas, “Increased reimbursements pay off.” ↩

- Jacqueline Rabe Thomas, “Officials: Efforts to reduce racial isolation need overhaul,” The CT Mirror, December 8, 2010, http://ctmirror.com/story/8653/officials-efforts-reduce-racial-isolation-need-overhaul. ↩

- Connecticut General Assembly, Joint Committee on Education, Ed Committee Hearing Transcript for 06/20/2007, (2007), http://www.cga.ct.gov/2007/eddata/chr/2007ED-00620-R001300-CHR.htm. ↩

- Robert A. Frahm, “Ads urging parents to keep children in Hartford schools anger Sheff lawyer,” Hartford Courant, April 29, 2011, http://www.ctmirror.org/story/12413/stay-city-schools-hartford-advises-parents. ↩

- Pedro A. Noguera, City Schools and the American Dream, New York: Teachers College Press, 2003. ↩

- “Hartford-Resident Student RSCO 2010-2011 Magnet School Placement Odds,” Hartford, CT: The CT Mirror, 2011, PDF, http://www.ctmirror.org/sites/default/files/documents/wait%20list.pdf. ↩

- Jacqueline Rabe Thomas, “With deadline looming, state still far from finish line on integrating Hartford schools,” Hartford Courant, November 21, 2011, http://www.ctmirror.org/story/14578/deadline-looming-state-still-far-finish-line-integrating-hartford-schools. ↩

- Frahm. ↩