New York City’s horror stories used to primarily entail the amount of crime and violence on the streets. Today, however, many of the most horrifying tales are concerning parents and their desperate and relentless scramble to get their children into the most elite and prestigious private preschools. That said competition for admission to New York City’s private preschools is incredibly fierce with over fifteen applicants for every available spot. “Next year is going to be even worse,” warns Amanda Uhry, the owner of Manhattan Private School Advisors (Nursery University). Roxana Reid of Smart City Kids adds, “Several nursery schools had ten or more children shut out from getting into school altogether last year” (Nursery University).

As time has progressed and more studies emphasizing the importance of early childhood development have been conducted, preschools have evolved drastically both in their purpose and importance to society. Although private preschools have been highly sought after in New York City since their origins, in recent years the competition to get into these elite schools has never been greater. In fact, competition has reached such extremes that the admissions process to get into these schools has been completely transformed. Due to the combination of extreme wealth, change in demographics, the public’s perception of preschools, and the urban baby boom that has occurred in New York City, getting into a private nursery school isn’t quite as easy as the A, B, C’s.

Brief Overview of the History of Preschool and Its Development in the United States

The first nursery schools appeared in the United States in the nineteenth century with the growth of the factory system. They were generally privately financed, designed for upper and upper middle class children under the age of five, and were typically affiliated to universities (McMillan). Moreover, they were often the places where child studies and psychological theories concerning children and their families—such as those of Sigmund Freud and Jean Piaget—were conducted (Read). As such, they formed part of a broader development of the professionalizing field of child welfare and development (Read). In the 1920s, however, the nursery school began to evolve when parents began getting involved in its running (Spodek).

Throughout the majority of the twentieth century, the nursery school began to integrate itself into public education systems around the country—though this effort was largely constrained by the high expenses and the general conception that the best place for young children was at home with their mothers (Beatty). Exceptions were made, however, for the children living in poor urban areas and in times of national emergency, such as during the Great Depression and World War II (Beatty). Day-care centers without the educational rationale of nursery schools still remained to dominate the area however (Beatty).

In the mid-1960s, the federal government undertook War on Poverty programs, such as Project Head Start, which provided nursery school experiences for underprivileged children (Beatty). These projects determined how important the first years in a child’s life are in respect to establishing healthy attitudes, a sense of values, intellectual interests, good learning habits and social behavior patterns–ultimately sparking the public’s interests and subsequently a drastic increase in public and private preschools, both in number and demand (Beatty).

The Importance of Early Childhood Education

President Obama recently emphasized the importance of quality preschool education in his State of the Union message, insisting on a substantial expansion:

“Every dollar we invest in high-quality early education can save more than seven dollars later on – by boosting graduation rates, reducing teen pregnancy, even reducing violent crime,” Mr. Obama said in his speech. In his budget, he requested $75 billion over 10 years to help states dramatically expand preschool options for low-income children” (Paulson).

In recent years, early childhood education has gained a great deal of attention from both the public and the press. Data has shown how beneficial high-quality early childhood education is in respect to a child’s future academic success (Pepper). Dr. Steven Barnett, director of the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) says that “Children who attend high-quality preschool enter kindergarten with better pre-reading skills, richer vocabularies, and stronger basic math skills than those who do not.” Scientific research has supported this argument. It is reported that approximately 90% of the brain develops before the age of five. Additionally, the first three years are supposedly the most vital in determining the child’s “brain architecture” (Gallen). The most recent of the NIEER reports claimed that children in high-quality programs earn approximately $143,000 more over their lifetime than the control group — and are less likely to smoke (Goldman). Although some argue that the beneficial impacts of preschool decreases over time, this is accredited to differences in the quality of preschool (Pepper).

New York City

In New York City, parents are facing a severe shortage of prekindergarten seats in public schools, with eight applicants for every available spot in some neighborhoods (Beekman). In spite of the city investing approximately $20 million this year to add 4,000 full-day prekindergarten seats in lower-income communities, the city is struggling to meet demand—especially in Manhattan and Queens (Beekman). Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, argues “We can’t continue to be a city where only a fraction of our kids has access to early education” (Beekman). The crisis is most evident in Brooklyn’s District 20 where allegedly more than eight children compete for every available spot. Additionally, Battery Park City’s Public School 89 had a prekindergarten admission rate of 7% (Beekman).

Given the amount of competition there is to attend one of the City’s public preschools, parents have turned to alternative academic routes. One of the most popular alternatives is sending their children to one of the private preschools. As Omar Davis, a Manhattan dad of two, explains, “There aren’t a lot of good resources for pre-K kids that aren’t private” (Beekman) However, competition to get into these private pre-kindergarten schools makes getting into Harvard look easy.

Change in Population

It is reported that the combination of extreme wealth and the urban baby boom has made private nursery school admissions incredibly competitive. In a place as affluent as Manhattan, the number of people willing to spend $15,000 a year tuition for private nursery school has flourished in recent years. This is in large part due to the rise in the white population and an increasing number of upper and upper-middle-class families staying in the city as opposed to moving to the suburbs.

According to 2010 Census estimates, for the first time since the 1970s, Manhattan’s population is predominantly non-white Hispanic (Roberts). The percentage of whites has increased exponentially from 40% in 1990 to 51% in 2009 (Roberts). In Lower Manhattan, the white population increased approximately by 25% between 2000 and 2005 (Roberts). Many accredit this increase in population to the increase of whites working on Wall Street and younger couples who stay in the city to start and raise their families (Roberts). Manhattan borough president, Scott M. Stringer, interprets the consequences this change in population has: “the borough is becoming a place for very, very wealthy people and enclaves for poor people and that middle-income people are finding it impossible to stay here” (Roberts).

In addition to the influx of wealth, the borough has also experienced a drastic increase in young children due to an urban “baby boom”. The Census Bureau approximates that the number of children in Manhattan under the age of five has increased by approximately thirty percent between 2000 and 2006 (Saulny). This is incredibly problematic in respect to entrance into schools as “New York City has about half the capacity it needs for its youngest students, public and private,” contests Betty Holcomb, the policy director of Child Care Inc., “Even if you’re rich, you’re not guaranteed a place in a preschool” (Saulny).

This change in the demographics of Manhattan’s population translates to a change in values and ideals of the society as well. In his article, “The Price of Perfection,” author Michael Wolff comments on the complete transformation of Brearley, the preschool his daughter had attended, from when his wife had graduated in 1970. He notes that this shift mirrors the change that has occurred overall in Manhattan:

“My wife’s Brearley class differs substantially from my daughters’ classes. My wife’s classmates were children of writers (predominantly, it seems, New Yorker writers), Columbia academics, publishers, doctors, and lawyers as well as socialites and product brand names — most of whom have largely been replaced in my daughters’ classes by the children of people in the financial industry. This clearly mirrors what has happened in the city itself — banking, providing never-before-imagined levels of cash flow and vastly scaled-up net worths, has changed these schools as it has changed (sleeked up, amped up, intensified, competified) Manhattan life” (Wolff)

Ronnie Moskowitz, director of The Washington Market School (TriBeCa), comments on the transformation of TriBeCa from “the old-hippie network”

to “the old-boy network”: ”It’s a new generation of parents,” she said. ”It’s the $2 million lofts. We were used to having aging hippies here and artists and pioneers. They were willing to live without much, no shoe stores or supermarkets. Now, parents walking in are asking about reading and worrying about testing. They’re parents who’re afraid of being judged.”

As the economic and social returns associated with college attendance flourish rapidly, higher education has become progressively more important to American social and economic mobility. That said to succeed in today’s global economy, a quality education has become essential. To many Americans a “quality” education translates to mean one that is solely attainable from an Ivy League College (Chan).

From Preschool to Princeton

As college admissions have become increasingly more competitive over the years, upper-middle and upper-class City parents have become increasingly more concerned about their child/children attending the right high school (Nursery University). Considering that the majority of private schools tend to children in grades K-12, admission to a quality preschool has taken on vast meaning. The competition for preschools is not merely over the quality of the nursery school, but rather the schools in which the preschool feeds the children to in the ensuing years (Nursery University). Most specifically, what many refer to as the ”Baby Ivies” — the private schools that have a reputation for their students gaining admission to the Ivy League schools (Nursery University).

The New York Daily News featured an article concerning Nicole Imprescia, a Manhattan mother, suing York Avenue Preschool for “jeopardizing” her daughter’s chances of getting into an elite private school, or one day: the Ivy League. Allegedly, the court papers filed by Ms. Imprescia implied that the school has essentially damaged her child’s chances of getting into a top college, citing an editorial that recognizes preschools as the first step to ‘the Ivy League’ (Martinez). “When their 4-year-old doesn’t get into preschools,” education journalist, James Atlas, says, “many of these social elite think it’s the beginning of the end. They didn’t get on the track. It’s not gonna happen for them. They might have to move to the suburbs. Every dire possibility unfolds before your eyes” (“Nursery School Scandal”). One must question how it is possible to even attain and formulate a legitimate argument against a preschool for supposedly “ruining” a child’s future academic success. The argument lies in the Early Childhood Admissions Assessment (ECAA), a standardized test used for lower elementary admissions for private schools in New York City.

The Early Childhood Admissions Assessment (ECAA)

The Educational Records Bureau, known colloquially as the ERB, issues the Early Childhood Admissions Assessment (ECAA) for lower elementary admissions for NYC private schools (Jones). The ECAA (most commonly referred to as the ERB) was developed in the 1960s to prevent children who were applying to multiple private schools from having to take numerous tests (Jones). It is comprised of a series of assessment tests designed to measure cognitive abilities and current development level (Jones). For preschoolers, the test is made up of eight sections—four that test verbal skills and four that test non-verbal skills including picture concepts, coding block design, and matrix reasoning (Jones). The scores are then combined to make a full scale composite score.

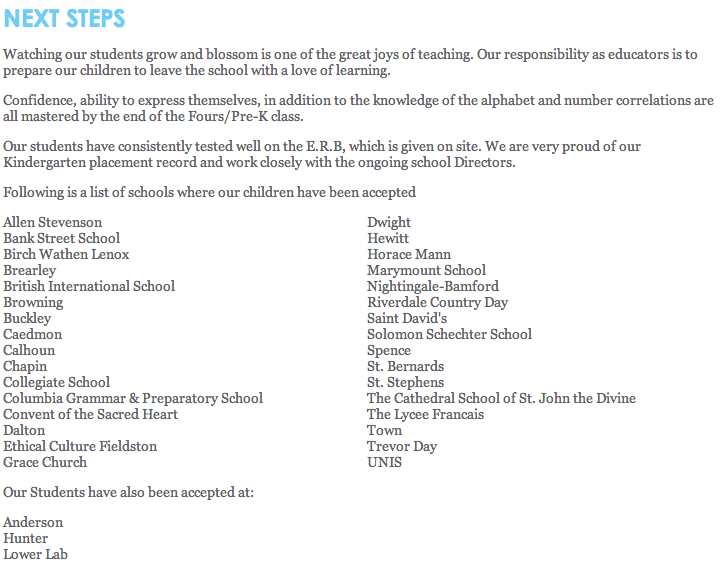

In New York City, the ERB has been interpreted by the public to be the determiner of a child’s future academic success. In large part this is accredited to the fact that it is an important component of a prospective student’s application to lower elementary private schools. Needless to say, many of the most competitive preschools acknowledge this and use it to their advantage to draw in future applicants (Anderson). York Avenue Preschool, for example, claims on their website that their students have consistently tested well on the E.R.B and that they “are very proud of [their] Kindergarten placement record and work closely with the ongoing school Directors,” accompanying this claim with a list of schools their children have been accepted into.

The Mandell School, another highly respected preschool in New York City, also features a separate file for the schools their students have been admitted into over the years. Evidently, these preschools acknowledge the significance of the E.R.B. and many have developed curriculums that essentially “teach to the test”—making them even more desirable and the competition even fiercer.

The Building Blocks of Future Academic Success

As previously stated, many of these competitive private preschools have adapted curriculums essentially catered to preparing children for the E.R.B. Rather than allowing the children to whittle away the days of early childhood playing dress-up or chasing one another around the playground, these preschool programs enacted expose them to games and activities that help the kids develop a wide range of skills needed to perform well on the test. These games and activities go far beyond building blocks and coloring, however.

At Horrace Mann, where tuition costs approximately $26,880, four-year-olds are taught reading and computer readiness (Goldman). At the 92nd Street Y, a highly respected preschool in the City, children participate in an archeology “dig” and sculpture projects (Goldman). These are only two examples that provide some insight to the many diverse and advanced programs these private preschools offer. In reality, the vast majority of these highly sought after schools offer students on-staff child psychologists, yoga and music specialists, and language professionals (Goldman). Many even offer on-site testing for the ERB to insure matriculation at a good private kindergarten (Goldman).

Admissions

The admissions process has become incredibly stressful for parents where observed play sessions, time-consuming interviews, escalating tuition costs and application fees, and preferences shown to legacies of the school have become the norm (Anderson). To cope with such an exhausting process, many anxious New York parents have even hired professional school placement consultants, such as “Smart City Kids” to get their children one of the limited, coveted seats (for the price of $4,000). With a preschool application process that resembles that of a collegiate one, it is not surprising that such corporations exist in the competitive environment of New York City (“Nursery School Scandal”).

At many of the most elite private preschools, such as Episcopal and Christ Church Day School, parents and children meet independently with the director and a few teachers for an interview. Other schools hold play-date ”interviews.” At the Y, for example, a small group of parents, their children and teachers assemble in a room and interact with one another for approximately forty-five minutes. One parent, an investment banker, recollects on her experience of taking her 20-month-old son on an interview at the City and Country preschool: ”The head of [City and Country], the head of admissions and several teachers were observing and taking notes on a clipboard, ‘I wondered, ‘What are they looking for? What are they writing down while he’s playing at the water table?”’

The truth of the matter is that the admissions process for these top preschools is incredibly daunting and difficult. The application process begins on the Tuesday after Labor day—a day many New York City parents refer to as “Black Tuesday” (Greene). This is the first and arguably most vital step in the process as it is the day that most private nursery schools send out their applications. If parents were to miss this day, they will not be able to receive an application to those schools for the year. That said parents are advised to start calling at nine in the morning, considering that many of the schools run out of their applications by noon. “Staying organized and on top of those dates and deadlines is really critical,” Roxana Reid, educational consultant and founder of Smart City Kids, adds, “Otherwise, you can be out of the process before you even get started” (Greene). Once parents receive the applications for the respective schools, the ensuing months are filled with open houses and interviews. This step in the process is incredibly vital in determining an applicant’s success as it is not only the children being evaluated, it is the parents as well. Wendy Levey, Director of Epiphany Community Nursery School, explains that school directors are “looking for families who will be a positive part of the community,” and therefore parents should, “From start to finish, treat the process with respect, care, and attention” (Greene). Moreover, many of the preschools require parents to compose short essays that entail discussing the child’s strengths, weakness, and other personal attributes. This task, though seemingly simple, has proven itself to be incredibly challenging for parents as many have expressed the difficulty of “profiling” an 18-month-old (Saulny). Rabbani, Manhattan father of two, asks, “What do you say about someone who just popped out?” “You’re just getting to know them yourself” (Saulny). After all of the applications have been completed and open houses have been attended, parents are encouraged to send a “first choice letter” to their favorite school. All that there is left to do is wait.

The sad reality is that regardless of how qualified an applicant is, acceptance to one of New York City’s private preschools is not guaranteed. Subsequently, parents invest heavily into recommendations, connections, and referrals. Needless to say, connections matter—and many of Manhattan’s most powerful and well connected are willing to go through great lengths to secure their children spots. Jack Grubman, former telecom stock analyst and multimillionaire, is one man that will attest to this claim. Once considered a highly respectable figure on Wall Street, Jack Grubman was convicted of giving a favorable rating to AT&T stock in exchange for his twins’ acceptance into the 92nd Street Y in 2002 (“Nursery School Scandal”). In addition to this scandal, he had Citigroup donate one million dollars to the Y. Needless to say, his children got accepted into the school though the representative from the Y stated that the large donation had no influence in the decision (“Nursery School Scandal”).. Arthur Levitt, former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, commented on the scandal and explained how this occurrence is hardly confined to this one example: “…buying entry into these schools has gone on in the elite community for as long as I can remember. Some of them tell you how much you have to put up, some of it’s done by winks and nods” (“Nursery School Scandal”).

Conclusion

The unfortunate truth of the matter is that the nursery craze largely involves white and affluent parents who perceive acceptance into these schools as a determinant of self-worth in New York City’s elite social circles (“Nursery School Scandal”). That said it appears almost as though the children are mere products and the parents are consumers. Preschools are supposed to be the places where children meet their first friends, learn to share, and bask in the innocence of childhood. The cutthroat competition that has emerged for entrance into these prestigious New York City private preschools contradicts the real purpose of preschool.

The Ethical Culture Fieldston School opened its doors to eight children of the working poor in 1878. It was founded by Felix Adler who firmly believed that the children of the poor should and deserved to be educated. By 1890, the school expanded to accommodate the upper-class after they had began expressing interest in attending. Today, tuition costs approximately $30,000 per student. It is ironic that this school, primarily designed to serve children of the poor-and-working-poor classes, has evolved into an institution that caters to the most advantaged of families. With an annual tuition of $30,000 and an application form that has a $60 fee, applying to this school is practically impossible if you are not financially sound. To conclude, private preschools in New York City have evolved from institutions designed to provide relief for disadvantaged and low-income families to an institution that symbolizes pride, status, and success for the wealthy parents of New York City.

WORKS CITED

Anderson, Jenny. “At Elite New York Schools, Admissions Policies Are Evolving.” The New York Times, September 5, 2011, sec. N.Y. / Region. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/06/nyregion/at-elite-new-york-schools-admissions-policies-are-evolving.html.

Barnett, W. Steven. “Benefits of Compensatory Preschool Education.” The Journal of Human Resources 27, no. 2 (April 1, 1992): 279–312. doi:10.2307/145736.

Beatty, Barbara. 1995. Preschool Education in America: The Culture of Young Children from the Colonial Era to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Beekman, Daniel. “Exclusive: Not Enough Free City pre-K Programs as Applications Outnumber Available Seats 8 to 1 in Some Neighborhoods.” NY Daily News, March 4, 2013. http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/city-pre-k-applicants-outnumber-seats-8-1-nabes-article-1.1278608.

Chan, Sewell. “Nursery School Frenzy, Caught on Film.” City Room, November 17, 2008. http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/11/17/making-sense-of-the-nursery-admissions-craze/.

Gallen, Thomas. “The Importance of Pre-kindergarten Education | Other Opinions | Bradenton Herald.” Bradenton, March 17, 2013.

Goldman, Victoria. Manhattan Directory of Private Nursery Schools, 6th Ed. 6th ed. Soho Press, 2007.

Goldman, Victoria. “The Baby Ivies – New York Times.” New York Times, January 12, 2003. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/01/12/education/the-baby-ivies.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm.

Jones, Elise. “ERB Testing: What the Heck Is the ERB and What Do Moms Need to Know?” Mommybites New York, December 28, 2011. http://mommybites.com/newyork/12/28/erb-testing-what-the-heck-is-the-erb-and-what-do-moms-need-to-know/.

Jr, John E. Pepper, and James M. Zimmerman. “The Business Case for Early Childhood Education.” The New York Times, March 1, 2013, sec. Opinion. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/02/opinion/the-business-case-for-early-childhood-education.html.

Kuczynski-Brown, Alex. “New York Class Size: Nearly Half Of Public Schools Have Overcrowded Classrooms, UFT Says.” Huffington Post, September 26, 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/09/26/new-york-class-size-uft_n_1914357.html.

Martinez, Jose. “Manhattan Mom Sues $19K/yr. Preschool for Damaging 4-year-old Daughter’s Ivy League Chances,” March 14, 2011. http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/manhattan-mom-sues-19k-yr-preschool-damaging-4-year-old-daughter-ivy-league-chances-article-1.117712.

“Nursery School Scandal.” ABC News, January 5, 2006. http://abcnews.go.com/2020/story?id=123782&page=1.

Paulson, Amanda. “Pre-K Programs Take Biggest State Funding Hit Ever.” MinnPost, April 30, 2013. http://www.minnpost.com/christian-science-monitor/2013/04/pre-k-programs-take-biggest-state-funding-hit-ever.

Read, Katherine H., and June Patterson. 1980. The Nursery School and Kindergarten: Human Relationships and Learning, 7th ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Roberts, Sam. “White Population Rises in Manhattan.” City Room, June 4, 2010. http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/04/white-population-rises-in-manhattan/.

Sangha, Soni. “For City Parents, a Waiting List for Nearly Everything.” The New York Times, February 22, 2013, sec. N.Y. / Region. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/24/nyregion/for-new-york-city-parents-a-waiting-list-for-nearly-everything.html.

Saulny, Susan. “In Baby Boomlet, Preschool Derby Is the Fiercest Yet.” The New York Times, March 3, 2006, sec. Education. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/03/education/03preschool.html.

Simon, Marc H., and Matthew Makar. Nursery University. DOCURAMA, 2009.

http://www.bradenton.com/2013/03/17/4437631/the-importance-of-pre-kindergarten.html.

Spodek, Bernard, and Olivia N. Saracho. 1994. Right from the Start: Teaching Children Ages Three to Eight. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

#next_pages_container { width: 5px; hight: 5px; position: absolute; top: -100px; left: -100px; z-index: 2147483647 !important; }

This essay calls our attention to the increasingly competitive application process for private preschools in New York City, and argues that this trend has been caused by shifts in wealth, demographics, perceptions of the importance of preschool, and the urban baby boom. (Is the baby boom simply an example of demographic change?) The body of your essay raises another factor – “a severe shortage of prekindergarten seats in public schools” — but without more evidence, we cannot tell if this shortage has become more severe over the past decade. If free quality PreK slots are shrinking in the public sector, that might help to explain rising demand in the private sector. Good evidence on Manhattan’s increase in white residents from the financial sector and how their concerns have changed the tenor of selective preschool admissions. I’d be curious to learn about the first time that “Baby Ivies” appeared in full-text databases like the NYTimes or Internet Archive. Good explanation of the ERB and the 2002 Grubman scandal, though it would have been helpful to know when private preschool consultants came onto the scene. Overall, I can imagine an expanded and revised version of this essay appearing as an article for a NYC print or web publication, if you wish to pursue it further.

My comments above are based on the Ed 300 research web-essay criteria:

http://commons.trincoll.edu/edreform/assignments/research-essay-process/

One additional suggestion about writing style:

The first two lines of the essay struck me as hyperbole. Are stories about wealthy parents seeking entry for their children to elite private preschools truly the “most horrifying tales” about NYC today? Do they outweigh the tragedies of marginalized students whose families lack the money to even contemplate these options? I encourage you to look for better ways to write about privileged people and their pursuit of education while keeping it in perspective. The last sentence of your essay does a better job on this aspect.

Well-written and interesting piece covering an issue that’s close to my heart and area of study (having been closely involved in starting a preschool for low-income children in Middletown last year). This is a really sad reality, especially as the achievement gap can be traced back to early childhood experiences.

This is a really good cross-sectional snapshot of the current state of competitive preschool admissions policies. In your last paragraph describing the Fieldston preschool, you mention how it has grown and changed over the years—I would love to see a little more analysis of how preschools have become more competitive over time. I’d also personally be interested in knowing more about the availability and quality of public preschools in NYC, though I know that’s not the subject of this paper.

Great job!