“No excuses” strategies have long been a method of teaching in many schools in America. The phrase “no excuses schools” refers to predominantly charter schools that concentrate on raising test scores of children of low-income and minority parents in a strict, orderly, and intentionally regimented setting. High academic standards are set for students because these schools promote a college-going culture. Not only is high academic achievement expected of students but also they have to attend school for longer hours and adhere to strict rules. Students who are lower performers have to take extra hours during the weekend because there is no excuse to lag behind. The concept behind this model reflects the idea that “every student, no matter what his or her background, is capable of high academic achievement and success in life” (Thernstrom). There are many schools in the US that are referred to as “no excuses schools,” therefore, the following questions could be addressed: why did “no excuses schools” appear? How and when did the phrase “no excuses schools” arise in the US? Has negative and/or positive connotations of the term changed over time?

The reason why “no excuses schools” developed in the United States in the 1990s can be traced back to the accountability movement and A Nation at Risk report. Despite the fact that “no excuses schools” existed since the 1990s, the phrase “no excuses schools” only appeared in 2000. In the 1990s and the 2000s, “no excuses schools” had rather positive connotations, whereas today it is more associated with unhappy children and ineffectiveness.

“No excuses schools” developed in the United States in the 1990s due to the accountability movement, and A Nation at Risk report. After the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision that made segregation illegal in schools in the US, another issue was addressed: major gaps between the academic performance of white students and minority students existed. This led to the Elementary and Secondary School Act of 1965, which claimed that schools in disadvantaged neighborhoods would get the necessary resources to provide an adequate education to the students. In order to monitor whether these objectives were met, school district became accountable for meeting academic standards. Ever since this era, school accountability has increased and made the achievement gap more apparent, and reached its peak in 1983 when one of the most significant and influential documents was issued by the government: A Nation at Risk report.

A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform played a significant role in the development of “no excuses schools” (Goldstein 118). A Nation at Risk was a report, which was produced by President Ronald Reagan’s National Commission on Excellence in Education, marking a significant turning point in the American educational system because it confirmed that American public schools were failing. It stated that the average SAT scores dropped over 50 points in the oral section and 40 points in math between 1963-1980. Not only did the report highlight the underachievement of American students but it also harshly criticized American teachers (Nation at Risk). Therefore, “no excuses schools” became necessary to address this problem and try to reduce the achievement gap. There were a significant number of charter schools in the United States that adopted the “no excuses” strategies. Some of the most prominent and successful “no excuses schools” besides KIPP Academy are Promise Academy, YES Prep, Uncommon School, Achievement First, and Aspire charter schools (Angrist 15).

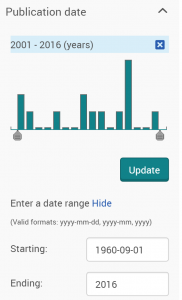

“No excuses schools” existed way before the term “no excuses schools” was developed, and only after Samuel Casey Carter labeled them as “no excuses schools” in 2000 when they started to be perceived as “no excuses schools.” Dana Goldstein, journalist and the author of the New York Times bestseller The Teacher Wars: A History of America’s Most Embattled Profession, claims that “no excuses schools” arose at the same time as Teach for America in 1989 and “no excuses” teaching became popular and gained prominence in the mid-1990s. Despite the criticism that is directed to “no excuses schools,” these strategies are still fairly dominant according to Goldstein (141). However, the phrase “no excuses schools” first appeared in 2000. Despite the fact that educational reformers started to use the phrase “no excuses” in connection with closing the achievement gap between low-income students and middle-class students, the phrase “no excuses schools” was first used by Carter in his book No Excuses: 21 High-Performing, High-Poverty Schools. Based on searching for the phrase “no excuses schools” in Ebsco, JSTOR, Google Scholar, and ProQuest News, I found that articles, essays, and reports were written by scholars, educators, journalists since 1989 stating that no matter the circumstances, all American students’ scores have to be improved: no excuses (Wasserman 30, “No Excuses for Failure,” “No Excuses”). However, only after Carter listed some schools referring to them as “no excuses schools” when this phrase became popularized. The first time the phrase appeared in a newspaper was in 2001 when Richard Rothstein wrote a review about Carter’s book in The New York Times .according to ProQuest News.

In No Excuses: 21 High-Performing, High-Poverty Schools, Carter gave credit to schools where educators insisted on academic excellence and they did not accept failure. Students attending these schools scored better than the national average in math and reading despite the fact that they were children of predominantly low-income minority parents (Carter 3). Many charter schools that embody the ideas of “no excuses” strategies are now called as “no excuses schools.” The phrase had very positive connotation at this time.

There are many scholars, journalists and researchers who claimed that “no excuses schools” are effective, even more effective than schools that do not use the “no excuses” model. In 2003, Thernstrom and Thernstrom wrote about “no excuses schools” as “excellent schools” (Thernstrom 272) that score well on statewide tests (Thernstrom and Thernstrom 43) in No Excuses: Closing the Racial Gap in Learning. In 2015, a meta-analysis about “no excuses schools” showed that these schools have positive and significant impacts on student academic achievement. Cheng et al. found that both the oversubscribed “no excuses schools” and charter schools produce better results on math and ELA tests compared to the national average. In addition, the results showed that “the estimated grand effect size for the sample of No Excuse charter schools are consistently higher than those estimated for the more general sample of random assignment charter school studies (Cheng et al. 21).” Based on their meta-analysis, Cheng et. al found that “no excuses schools” increased student achievement by “0.25 and 0.16 deviations in math and literacy, respectively, net of the typical annual growth that students experience.” Furthermore, Promise Academy in the Harlem Children’s Zone showed that their students gain 0.229 standard deviations in math per year and 0.047 standard deviations in reading that meant that the school closed the achievement gap in math in four years and halved it in reading (Fryer 2).

Despite the fact that “no excuses schools” had been perceived well and successful since their foundations due to their improved test scores, there has been a growing amount of literature that criticizes these schools. Goldstein claimed that “there has been little convincing evidence done on those “no excuses” teaching strategies: incentive systems (pizza for good behavior and high test scores)…Yet this type of teaching has exploded in prominence since the mid-1990s” (141). In an article “At Success Academy Charter Schools, High Scores and Polarizing Tactics,” Kate Taylor pointed out that Success Academy Charter Schools had “a system driven by relentless pursuit of better results, one that can be exhilarating for teachers and students who keep up with its demands and agonizing for those who do not.” By highlighting that “no excuses schools” are demanding, Taylor criticized the system that it might not be beneficial for all children who are enrolled in those schools. For example, at Success Academy Charter Schools, students’ academic achievement is not a private matter but one that is displayed on colored charts and those who are failing are in the red zone—a reminder every day that you are a failure (Taylor). Furthermore, these students who are behind and do not perform as well as they should are made to feel “misery.” Moreover, some students wet themselves during practice tests because teachers did not give them permission to go to the bathrooms. In addition, Taylor quoted a student attending one of the Success Academy Charter Schools saying “What I don’t like is I have to go to school on Saturdays, so I feel like I don’t get rest, and I get a lot of stress in my neck because I got to go like this all the time” [hunching forward as if he was taking a test] (Taylor).

Despite the fact that Taylor’s depiction of these “no excuses schools” are somewhat neutral, it can be argued that there are many elements in the “no excuses” model that are questionable in terms of its psychological effects on students. Furthermore, in “The Paradox of Success at a No-Excuses School,” Joanne Golann claimed that “as students learn to monitor themselves, hold back their opinions, and defer to authority, they are not encouraged to develop the proactive skills needed to navigate the more flexible expectations of college and the workplace…No-excuses schools thus promote academic achievement while reinforcing inequality in cultural skills. These findings suggest that what works for academic achievement may not coincide with what works for students’ success in later life stages” (115). By questioning the skills these students acquire, Golann points out that “no excuses schools” only focus on how to close the achievement gap while students are in schools but they do not consider long-term consequences and job opportunities (116). From these sources, it can be seen that critics of “no excuses schools” look beyond test scores, and question the effectiveness of “no excuses” strategies and their consequences for students later in their lives.

In conclusion, “no excuses schools” arose in the 1990s in the US primarily because the accountability movement and A Nation at Risk showing that public schools were failing and there was a significant achievement gap between middle-class white students and students of low-income and minority parents. They aimed at closing that gap by applying “no excuses” strategies, which became highly popular in the US because these “no excuses schools” generated better test scores. Many people advocated “no excuse schools” due to their improved scores, however, from the 2000s, more and more criticism had been addressed questioning the long-term effects of the “no excuses” model. It is not just simply a critique of the strict teaching methods and environment that are implemented in such schools but also a critique of standardized testing and the way how money is distributed among public schools. Further questions can be proposed: why are there still advocates of “no excuses schools” despite the fact that most of the literature on these schools criticize the “no excuses” model and there is no evidence for long-term success?

Bibliography

Angrist, Joshua D., Pathak, Parag A., Walters, Christopher R. “Explaining Charter School Effectiveness.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 5:4 (2013): 1-127. Web March 31 2016.<http://www.jstor.org/stable/43189451>.

Carter, Samuel Casey. No Excuses: Lessons from 21 High- Performing, High-Poverty Schools. Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation. 2000. Print.

Cheng, Albert, Collin, Hitt, Kisida, Brian. “No Excuses Charter Schools: A Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence on Student Achievement.” Education Research Alliance for New Orleans. (2015): 1-27.

Dana Goldstein, The Teacher Wars: A History of America’s Most Embattled Profession (New York: Anchor, 2015). ISBN 978-0-345-80362-7.

Fryer, Roland G. Jr. “Creating “No Excuses” (Traditional) Public Schools: Preliminary Evidence from an Experiment in Houston.” National Bureau of Economic Research. 2011. Web April 25 2016.

Golann, Joanne W. “The Paradox of Success at a No-Excuses School.” Sociology of Education. 88:2 (2015): 103-119. Web March 31 2016.

KIPP Foundation. 2009. Five Pillars. KIPP Foundation. Web March 31 2016.

<http://www.kipp.org/01/fivepillars.cfm>.

Lack, Brian. “No Excuses: A Critique of the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) within Charter Schools in the USA.” Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies. 7:2 (2015): 127-153.

McKenzie, William, Kress, Sandy. “The Big Idea of School Accountability.” The Bush Institute at the George W. Bush Presidential Center. 2015. Web. April 20 2016.<http://www.bushcenter.org/essays/bigidea/>.

“No Excuses.” Wall Street Journal, Eastern edition ed.: 1. Jun 01 1999. ProQuest. Web. 18 Apr. 2016 .

“No Excuses for Failure.” The Christian Science Monitor. Nov 04 1988. ProQuest. Web. 18 Apr. 2016 .

Paul Tough, Whatever It Takes: Geoffrey Canada’s Quest to Change Harlem and America (Boston: Mariner Books, 2009). ISBN 978-0-547-24796-0.

Taylor, Kate. “At Success Academy Charter Schools, High Scores and Polarizing Tactics.” The New York Times. April 6, 2015. Web 10 April 2016.

<http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/07/nyregion/at-success-academy-charter-schools-polarizing-methods-and-superior-results.html>

Thernstrom, A., Thernstrom, S. No Excuses: Closing the Racial Gap In Learning. New Work: Simon and Schuster. 2003. Print.

United States. A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform. Washington, D.C.: The National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983. Print.

Wasserman, Joanne. “‘No Excuses’ Policy a Winning Formula.” New York Daily News: 30. June 11 1999. ProQuest. Web. 18 April 2016.