Sex education formally became known as sex education during the late Progressive Era (1880-1920) in the United States. Before it was sex education, hygiene education was the most similar curriculum taught to students about their health. After it became sex education, the values and lessons have changed in many ways over the years, and the sex education during the 1920s was quite different from the sex education taught in most secondary schools today. Although much has changed, it is important to look back and examine the roots of the movement to bring sex education in to secondary schools, scrutinize its progress and its failures, and learn potential ways to advance sex education today.

This essay will explore the changes in sexuality education during the Progressive Era (1880-1920) and work to answer why hygiene classes partially transform into sex education classes in U.S. secondary schools in the Progressive Era. The shift from hygiene education to sex education in U.S. secondary schools occurred in the 1920s as a result of public health concerns that emerged from World War I, unprecedented government involvement through research, departmental cooperation, and funding, and shifting, more indulgent youth culture about health and sexuality. While these factors pushed change forward, the progress was only momentary and within a few years the progressive education experienced a conservative relapse because very same factors that had initially been transformative, became a detriment to change. The Great War ended, slowing the momentum that public health received, government funding and support waned, and the conservative culture prevailed, essentially ending the progress made for sex education during the Progressive Era.

Hygiene Education (pre-1920s)

Hygiene education in the United States before the 1920s Progressive Era focused primarily on cleanliness, immorality, and sexually transmitted diseases. The purpose of hygiene education was first, “to teach sexual morality” and second, to educate students on the “principles of hygiene” (Strong 141). In addition to the focus on morality, hygiene education excluded scientific information. Specifically, the American Federation for Sex Hygiene’s official recommendations for education included a guideline starting there should be “no study of external human anatomy [and] very limited study of internal anatomy” (Imber 349). The fixation on venereal diseases in hygiene education increased dramatically during World War I and the education surrounding it was based solely on fear tactics (Moran). Although these ideals were the primary focus of hygiene education before the Progressive Era, public health campaigns arising from WWI, new government involvement, and an opening of youth culture to sexuality momentarily increased awareness and support for the transition into sex education.

Transformation Factors

Public health campaigns that focused primarily on venereal diseases during World War I enabled sex education reformers to bring “unprecedented funding and acceptance to sex education” (Moran 200). The crusade for public health during this time brought the importance of sexual health to the forefront of health issues and heightened public support. The War Department’s campaign was multifaceted and intensive to combat venereal diseases. In fact, the War Department considered the fight against venereal diseases as a “matter of national security” (Huber 30). It included public outreach, pamphlets, education, and more. Soldiers were instructed to return from the war and provide information to their families, specifically their younger brothers, and become advocates in their home communities for prevention awareness, resources, and education (Huber). A pamphlet created in 1918 shortly after the war was over noted:

The War is Over! The last gun has been fired, the last bomb dropped, the last torpedo shot. But there is one enemy which has done more damage than the Germans ever thought of. This enemy is called the Venereal Diseases. The Government has been fighting them openly and energetically and much has already been done, but the battle is not yet over. It is a battle of peace times just as much as of war times. (Sex Education 130).

Another example of the crusade against venereal diseases is in the image found below, a billboard display in Pennsylvania during World War I.

https://archive.org/details/socialhygiene06amerrich/page/n3.

These campaigns were not only effective in generating public support, but also were successful in their mission because as a result of the War Department’s efforts, the venereal disease rate “dropped to the lowest rate ever reported” (Huber 30).

Additionally, the extent of this campaign and its open rhetoric changed the culture surrounding public health. Technology and medicine were advancing, which served to both increase developments and to illuminate the horrors and dangers of venereal diseases (Burnham). The rhetoric surrounding venereal diseases also began to diverge from the common fear tactics, which were proven to not be effective, and began to employ a moral argument about diseases (Moran). Much of the dialogue started to center around the “innocents” impacted by venereal diseases, like for example wives whose husbands had infected them (Burnham). Doctors even began to diagnose “syphilis of the innocent” in regards to certain cases (Burnham 891). This rhetoric continued to be utilized by a poster campaign called “Keeping Fit,” made by the American Social Hygiene Association in 1922. Below is a poster in the campaign that shows a gruesome image of a young boy who inherited syphilis from his father, causing him sever physical deformities. The poster urges men not to make their future children “pay the penalty of [their] mistake”.

The public campaigns initiated during World War I to fight venereal diseases succeeded in their missions, but also had unintended consequences that helped transform hygiene education to sex education during the Progressive Era. These campaigns brought public health, and specifically sexual health, to the forefront of conversations in both the public and medical fields and increased acceptance to the goals of sex education reformers. The reformers of the time perceived the weaknesses of these campaigns and decided to disseminate their message not through fear, but rather through encouraging the internalization of “affirmative rules of behavior” (Strong 140). Additionally, many sex education reformers believed that with the advances in technology and medicine, a cure for venereal diseases was imminent and they would therefore need a new approach to encourage chastity among the youth (Strong). The increased awareness of sexual health caused by campaigns during World War I stimulated support, approval, and new direction for sex education.

Government involvement in the form of research, departmental cooperation, and funding was also an essential factor for the transformation of hygiene education to sex education in secondary schools. In January of 1920, the United States Bureau of education and the United States Public Health Service collaborated to create a questionnaire seeking to gather sex instruction information in high schools (Edson). They received 6,488 replies detailing the state of the sex education instruction in each school: 1,633 provided emergency sex education, 1,005 provided integrated sex education, and 3,850 provided no sex education (Edson 593). Emergency sex education was instruction through “lectures, talks, sex hygiene exhibits, and pamphlets,” while integrated sex education was taught “incidentally in subjects of regular curriculum,” like Biology, Sociology, Physiology, or Hygiene (Edson 593). It was also reported that out of 1728 principals, over 80% of them were in favor of emergency sex education, even if it was not currently taught in their high school (Edson). Below is a chart created in the report detailing the sex education instruction in high schools by state in 1920.

United States.” The School Review, vol. 29, no. 8, 1921, pp. 593–602. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1077466.

Governmental involvement also included support from departmental cooperation. In 1919, the Federal Government issued that it was the responsibility of schools to teach sex education, but the United States Public Health Service took an “active role in guiding sex education the 1920s” and urged high schools to teach more than simply conception (Sex Education 135). In 1919, the United States Public Health Service cooperated with state boards of health and education and got over 5,000 requests for sex education pamphlets (Huber). In fact, by 1921, 47 out of 48 state boards of health worked to control and prevent sexually transmitted diseases with the Public Health Service (Huber). The government also provided significant financial resources to help fund sex education in high schools. The Chamberlain-Kahn Act in 1918 allotted $2 million to support sex education (Moran). The awareness, research, departmental cooperation, and funding were all significant transformative factors for sex education in the Progressive Era.

The more indulgent and sexually progressive youth culture in the 1920s also was a contributing factor that helped to develop sex education. Although, it is clear that the liberal ideas of both the sex education reformers and the youth culture progressed in tandem and were mutually beneficial because sex educators were “responsible for creating a foundation of sexual frankness and media freedom” that bolstered the youth cultural revolt against conservatism (Moran 80). The most visible aspects of this revolt were in female clothing style and new dances that were more outwardly sexual and promiscuous (Moran). Women were also becoming more sexually active at a younger age and in fact, it was reported that less women, a drop from 33% in 1900 to 23% in 1919, failed to achieve “even one orgasm in their first year of marriage” (Strong 134). Women, in particular, were becoming more outspoken about their sexual desires and bodies in general and this cultural change was reflected in high school sex education. Sex educators could not longer rely on the “innate purity of girls” to enforce chastity and had to adjust accordingly (Moran 82). In some cases, the female students assisted in this adjustment: in 1920 it was reported that a group of high school girls came together and requested that menstruation, female reproductive organs, and opportunities to answer questions about sexuality be included in the school’s sex education curriculum (Moran). Because of this cultural shift towards sexual frankness among adolescents, sex educators were motivated to adapt to the changes and incorporate “popular post war sentiments about individual fulfillment, mental health, and ‘positive’ sexuality into their programs” (Moran 89). After the First World War, the sex education garnered movement through awareness from public health campaigns, government support and funding, and progressive youth culture surrounding sexuality. These three factors initially pushed hygiene education into the 20th century, but within a few years, circumstances changed and the same three factors would contribute to the dissolution of Progressive Era sex education in secondary schools and the continuity of the older, more conservative ways.

Inhibition Factors

The momentum generated from campaigns during World War I centered solely around venereal diseases, but for a time, sex educators successfully diverted this support towards sex education. However, once the war ended in 1918 and the venereal disease campaigns began to weaken, so did the redirected support towards sex education because the two movements were “inextricably tied” (Moran 100). Sex educators were confident that after the war, the focus on public health would maintain strength and the attention would shift towards sex education or other health initiatives. Yet this was not the case, and the waning of support of both movements illustrated the failure of sex educators to “transfe[r] the momentum of the anti-venereal disease crusade to their own program” (Moran 108). Additionally, the funding from Chamberlain-Kahn Act, passed in 1918, to combat venereal diseases and support sex education programs rapidly decreased by 1922 because the funding was also closely tied to the War Department’s effort (Sex Education). Moreover, by the end of the decade, the United States Public Health Service officially withdrew support from sex education to appropriate funds to more “controversial projects” (Moran 108). These cuts in funding and support were also exacerbated by the Great Depression soon to come. Now that national support and federal funding was essentially cut from sex education, the movement could only be sustained by individuals. However, those who answered this call were part of the older social hygiene societies and these individuals became the majority of support and leadership for sex education in high schools (Moran).

Even before waning support from the public and the federal government, the sex education movement “paid the price for [its] new freedom of discussion,” with the unwanted addition of “moral idealism” added to the conversation (Burnham 905). Although the sex education reformers aimed to change the previous Victorian morality that dominated hygiene education, they did not introduce new morals into the curriculum, and chose to focus on science (Huber). The reformers thought by emphasizing science, rather than morals, they could “de-eroticize sex” and keep their message pure (Strong 148). Yet, when sex education moved “from the abstract to the physical,” to many it also moved “from the noble to the pornographic” (Strong 132). Ironically, by attempting to avoid morality in sex education, it caused many to believe that now, more so than ever, was morality needed in discussions of sexuality, especially now that the conversations were so open and explicit to follow the youth culture. Because the sex education reformers did not have new moral messages, older Victorian morals of the 19th century infiltrated the curriculums (Strong). This insertion was only exacerbated by the perceived rapidity of youth to “rush into sexual misconduct,” causing moral messages to become more stringent and controlling, especially of female sexuality (Moran 90).

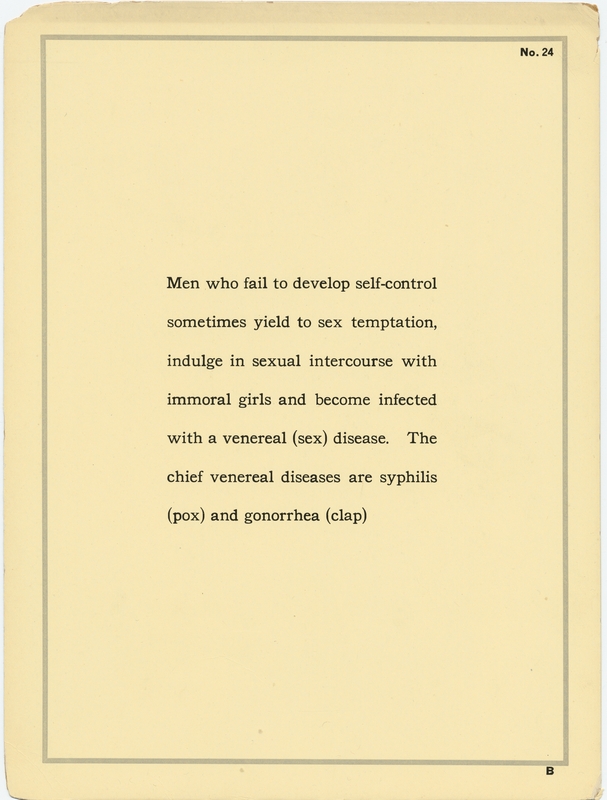

The new orthodoxy in sex education stigmatized sexually open young women as not only “immoral but also socially deviant and unfit for marriage” (Moran 96). A clear example of this double standard is illustrated in the United State Public Health Service’s “Keeping Fit” campaign posters in 1922. The campaign was aimed exclusively for young men and ways to keep their sexuality healthy. The image below demonstrates efforts to alleviate concerns about male sexual development and normalize their process, instructing the boys not to worry about seminal emissions, without any mention of female sexual behaviors.

Additionally, a blatant contraction about female sexuality is seen in the two posters from the campaign shown below. The first shows a young women looking directly at the audience and smiling. The caption reads: “Somewhere the girl who may become your wife is keeping pure. Will you take to her a life equally clean?” This message places the onus on men to protect the innocent women from venereal diseases. However, in the second poster, “immoral girls” are to blame for the cause and spreading of venereal diseases.

Although sex educators “tied their efforts to some of the age’s dominant cultural trends” to follow sexually progressive youth culture, the values of sex education remained inextricably connected with “essential attributes of the Victorian moral code” (Moran 96). Because of the lack of support and funding after World War I and because of the conflation of medicine and morality, the initially strong and momentous sex education movement was “ultimately too obscure, uncoordinated, and diffuse to ensure its own survival” (Moran 109).

Conclusions

The transformation of hygiene education to sex education in U.S. secondary schools during the Progressive Era was pushed forward by three factors: public health concerns that emerged from World War I, government involvement through research, departmental cooperation, and funding, and shifting, more indulgent youth culture about sexuality. Yet, those same three factors all contributed to the demise of Progressive Era sex education just a decade later. The end of World War I and the Great Depression looming on the horizon meant that public support and government funding waned and was diverted to other, more seemingly important things. While the more progressive youth culture pushed sex education to more frank and open discussion about sex, the more conservative Victorian morals infiltrated the curriculums and held the progress back. Change and continuity are always on two sides of the same coin and are in a continuous battle for control. While many factors influence progress and stagnation, every generation must reflect on the past and continue to push forward towards change.

Bibliography

Blount, Jackie M. “The History of Teaching and Talking about Sex in Schools.” History of Education Quarterly, edited by Jeffrey P. Moran and Janice M. Irvine, vol. 43, no. 4, 2003, pp. 610–15. JSTOR.

Burnham, John C. “The Progressive Era Revolution in American Attitudes Toward Sex.” The Journal of American History, vol. 59, no. 4, 1973, pp. 885–908. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1918367.

Do Not Worry. 1922. American Social Health Association, http://gallery.lib.umn.edu/items/show/937.

Edson, Newell W. “Some Facts Regarding Sex Instruction in the High Schools of the United States.” The School Review, vol. 29, no. 8, 1921, pp. 593–602. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1077466.

Huber, Valerie J., Firmin, Michael W. “A History of Sex Education in the United States since 1900.” International Journal of Educational Reform, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 25-51. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1044808.

Imber, Michael. “Toward a Theory of Curriculum Reform: An Analysis of the First Campaign for Sex Education.” Curriculum Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 4, 1982, pp. 339–362. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1179488.

Inherited Syphilis. 1922. American Social Health Association, http://gallery.lib.umn.edu/items/show/948.

Moran, Jeffrey. Teaching Sex: The Shaping of Adolescence in the 20th Century. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2000.

Pure girl is waiting somewhere. 1922. American Social Health Association, http://gallery.lib.umn.edu/items/show/963.

Self-control and venereal disease. 1922. American Social Health Association, http://gallery.lib.umn.edu/items/show/945.

“Sex Education in the 1920s.” Sex Ed, Segregated: The Quest for Sexual Knowledge in Progressive-Era America, by Courtney Q. Shah, NED – New edition ed., Boydell and Brewer, 2015, pp. 130–140. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt13wzt5w.11.

“Social Hygiene.” The American Social Hygiene Association, vol. 6, no. 1, https://archive.org/details/socialhygiene06amerrich/page/n3

Strong, Bryan. “Ideas of the Early Sex Education Movement in America, 1890-1920.” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 2, 1972, pp. 129–161. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/366974.