The community college is an integral part of the equation in the American pursuit for education to function as societies’ great equalizer. It has a mission of open access for all, and the affordability of its programs supports this mission. While this might seem an ideal formula for providing upward socio-economic mobility for America’s students, the community colleges have evolved into institutions that support social class reproduction. The efficacy of these institutions needs to be examined to support the seven million students they currently educate. Inspection of the changes these institutions have made over the last fifty years must be considered in this evaluation. In order for an assessment to proceed, the question we must ask is: What factors caused the decline of social mobility among community college graduates since the 1960s?

Over the last century, the demographics of student populations at community colleges have changed drastically. Community colleges have responded to this demographic shift by transforming their curricula offerings. This has resulted in an increase in vocational, remedial, and business oriented certificate programs, and has reduced focus on Liberal Arts and Humanities transfer programs. A reduction of Liberal Arts and Humanities transfer programs limits baccalaureate attainment for community colleges students. The best course to promote socio-economic mobility of students is through attainment of a baccalaureate degree. Community colleges have become sponsors of social class reproduction for many of their students due to the increase in vocational, certificate, and remedial courses which limit opportunities for socio-economic mobility.

DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT

A shift in the demographics of students attending community colleges began in the 1960s and proceeded through the 1970s. Prior to this demographic shift, and the ensuing curricula changes, community colleges sustained programs for socio-economic mobility of their students. J.M. Beach Gateway to Opportunity clarifies, “the students who enrolled in community colleges in the first half of the twentieth century were middle-class high school graduates who wanted to earn their bachelor’s degree and enter a white collar profession.” 1 Many factors contributed to this demographic shift. By the 1970s, when compared to the student populations at four year institutions, student populations at community colleges were disproportionally of low-income and minority students. 2 The suggestions of Beach, and others imply two important things about the changes that occurred in community colleges around the 1970s and into the twenty-first century.

It first infers that the original students of community colleges focused on an academic curriculum that facilitated transfer to four-year institutions. It suggests that the students who were attending community college in the first half of the twentieth century came prepared for college level course work. The role of community colleges as a stepping-stone to four-year institutions also suggests that the degrees awarded at community colleges were not constructed to be the only degree obtained by the students.

Brint and Karabel’s account examining the increase in enrollment of economically disadvantaged students allows for a second inference to be made about this changing demographic. Compared to the white middle class students that attended community college in previous generations, a disadvantaged student population represents students who need education to facilitate socio-economic mobility. This change was facilitated by the increased access to federal financial aid with the Higher Education Act of 1965 and the amendments to that act in 1972. This legislation was designed to improve access to higher education for low-income students and to promote mobility. The results were an inflation of low-income students at open-access institutions like community colleges.

Brint and Karabel confirm the existence of a demographic shift in The Diverted Dream. Their interpretation of the shifting demographic of community colleges and the reasons for its occurrence support the argument of open access policies and an increase availability of student aid. According to Brint and Karabel,

These funds, [federal student loans] combined with the growing number of open-door institutions located in or within easy access to minority populations, greatly increased the number of minority students in the nations community colleges… By the late 1970s, the major subordinate racial minorities, including blacks, were disproportionately concentrated in two-year institutions. 3

This increased access to higher education for low-income minority students is crucial to facilitating socio-economic mobility for marginalized populations. The change in community college curricula that follows contributes to the social class reproduction and is not a means of mobility for the students.

CURRICULA AND PROGRAM CHANGES

In 1972 The American Association of Community and Junior Colleges (AACJC) released an annual assembly report, which demonstrates their acknowledgement of shifting student demographics and their changes in curriculum offerings in light of this shift. The report states that community and junior colleges should develop programs that:

- Aim for the goal of equipping all their students for personal fulfillment, immediate gainful employment, or for transferability to a four-year college

- Provide working students … access to instruction at times and places convenient to them… consider using external degree life experiences

- Improve Faculty-Staff-community-student relationships

- Give equal status to vocational, transfer and general education, student personnel and community services

- Development of occupational educational programs linked to business, industry, labor, and government

- Utilize new concepts of education through a learning center, personalizing, if not individualizing the instructional process

- Be flexible to change, in a continuing effort to provide more effective educational services

- Define and integrate programs in terms of specific student and societal needs. For example: Bilingual and bicultural programs. 4

In light of the changing demographics, community colleges were forced to retool their offerings, but how could any single institution achieve everything on the above list? The introduction of the many responsibilities outlined by the AACJA led to an explosion of many documented curricula changes at community colleges.

In the 1970s, as a result of an escalation in disadvantaged students attending community college, an increase in remedial education courses began. 5 Remedial education typically involves courses in Mathematics and English that are below college level. While the need for remedial education at community colleges highlights a problem in K-12 education, the community colleges rose to their changing student needs. They developed programs based on the missions of the AACJC and the needs of their student populations. While remedial offerings seem necessary, they do not contribute to the mobility of the students at community colleges. Today, Complete College America reports that for every ten students seeking an Associates degree, five will require remedial education, and fewer than one of those ten will graduate in three years. 6

Brint and Karabel submit another curriculum change that occurred during the 1970s and into the 1980s. They describe that as a response to the countries’ fiscal crisis during the mid-1970s, community colleges began to make stronger ties to businesses with an increase in occupational and vocational programs. 7 This furthers the case that community colleges contribute to class reproduction instead of upward mobility. The increase in vocational programs, at a time when baccalaureate credentials were needed to enter the professional managerial class, affected the socio-economic gains provided by community college completion in the 1970s and 1980s.

In the 1980s, Fred L. Pincus “The False Promise of Community Colleges: Class Conflict and Vocational Education” further criticized the increase in vocational offerings. Pincus suggested that vocational offerings to community college students were an additional educational tracking mechanism that assured economic class reproduction of their students. 8 For disadvantaged, part-time, students, the quick track of vocational education may be glamorous, but is nonetheless a program that will assure working-class students become vocationally trained working-class adults. If community colleges promote and increase vocational offerings they are not adequately contributing to the upward mobility of their students. Instead, they are acting as vehicles of social class reproduction.

Kevin Dougherty, associate professor at Teachers Colleges of Columbia University is quoted by The Chronicle, echoing earlier sentiments of Pincus.

Community colleges and state systems increasingly take steps to make vocational programs seem more attractive, to ease prejudice against them — by building new vocational-program facilities, and by claiming in their publicity materials that graduates can make as much money coming out of vocational programs as they could by completing a baccalaureate degree. That may be true in some instances, but on average it is not. 9

Vocational education is not the correct route to socio-economic advancement, especially in a country of limited vocational employment opportunities. The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce projection reporting suggests that by 2018, 62% of employment will require some college education with more than half of that requiring a bachelors degree. 10

The late 1990s saw an introduction of yet another program offering at community colleges: contract training. Beach explains that contract training was a response to the increasing use of technology in business. The community college took on the role of training students for specific job placement opportunities that utilized technology. According to Beach, contract training may contribute to an increase in non-credit courses and a decrease in resources for the liberal arts. 11 Non-credit course work does not contribute to obtaining a bachelors degree. The argument can also be made that non-credit course work is terminal; it leads students to believe they are progressing towards higher education when the truth is they have not even begun educational advancement.

CONSEQUENCES OF CHANGE

The expansive curricula development at community colleges over the last half-century has resulted in three major problems for community colleges. The first is the offering of extensive remedial education programs. Statistics suggest that very few students who begin in remedial programs are not likely to complete community college. One could speculate that this is due to the time required to complete a program if semesters in non-college courses are necessary prior to entering a credit-gaining program. Furthermore, students who enter remedial education classes may never be proficient enough for college level course work.

Excluding remedial education programs jeopardizes the open access mission of community colleges. Students who require remedial education have no higher education opportunity other than access to community colleges. Three Rivers Community College (TRCC), Norwich, Connecticut is an example of the overabundance and inflated importance of remedial course offerings. For their Fall 2012 semester TRCC is offering one hundred and four classes with an ENGL distinction. Forty-five of these courses are courses that are pre-college level and only seven of the course offerings are of a 200 level distinction. 12 TRCC has placed a focus on remedial education. This does not support courses that teach and promote the higher-order thinking needed to transfer to four-year institutions. Remedial education can and will deviate attention away from Liberal Arts and Humanities transfer programs. It creates bottom heavy institutions of higher education that are not educating at a level higher than what is offered in high school.

The second problem is that massive amounts of program offerings have inevitably resulted in a reduced focus on Liberal Arts and Humanities transfer programs. These transfer programs are what will assist students in obtaining baccalaureate credentials. Brint and Karabel further analyze the decline of Liberal Arts at community colleges. They quote 1979 findings of Cohen and Lombardi who state, “except for U.S. history, Western civilization, American and State government introduction to literature and Spanish, little in the humanities remain.” 13 Strong transfer programs into baccalaureate level institutions are necessary for community colleges to provide socio-economic mobility for their students. Limiting these programs inevitably keeps disadvantaged students in the underclass.

The mission constructed by the AACJC in 1972 outlines multiple directions of curricula and program development, which have led to a disorganized system. Thomas Baily and Vanessa Smith Morest “Defending the Community College Equity Agenda” suggest, “the public community college was so overloaded with diverse missions that it was impossible to do any of them well.” 14 Community colleges do a disservice to their students by offering too much, and not excelling at enough.

The third problem inhibiting socio-economic mobility for the students of community colleges is the increase in promotion and funding of vocational and occupational programs. The Contradictory College concludes that community colleges, “were just ineffective, non-encouraging, anti-academic, low performing, and overly vocationalized.” 15 Additionally, an ethnographic study conducted in 1990 determined, “vocational education reinforced class inequalities.” 16 While there may be a place for vocational education, where the correct place is, is undetermined.

Vocational education funding has recently been seen as an easy fix to the problems associated with creating education opportunities’ for all. Recent legislation that first went to congress as a twelve billion dollar plan to increase graduation rates and transfer prospects for community college students known as the American Graduation Plan was changed in house negotiations. The end result was a two billion dollar plan to support career training. 17 Although the country values and rewards baccalaureate attainment and has an existing system that the first half of bachelors could be completed by many Americans it does not fund it.

THE BACCALAUREATE MATTERS

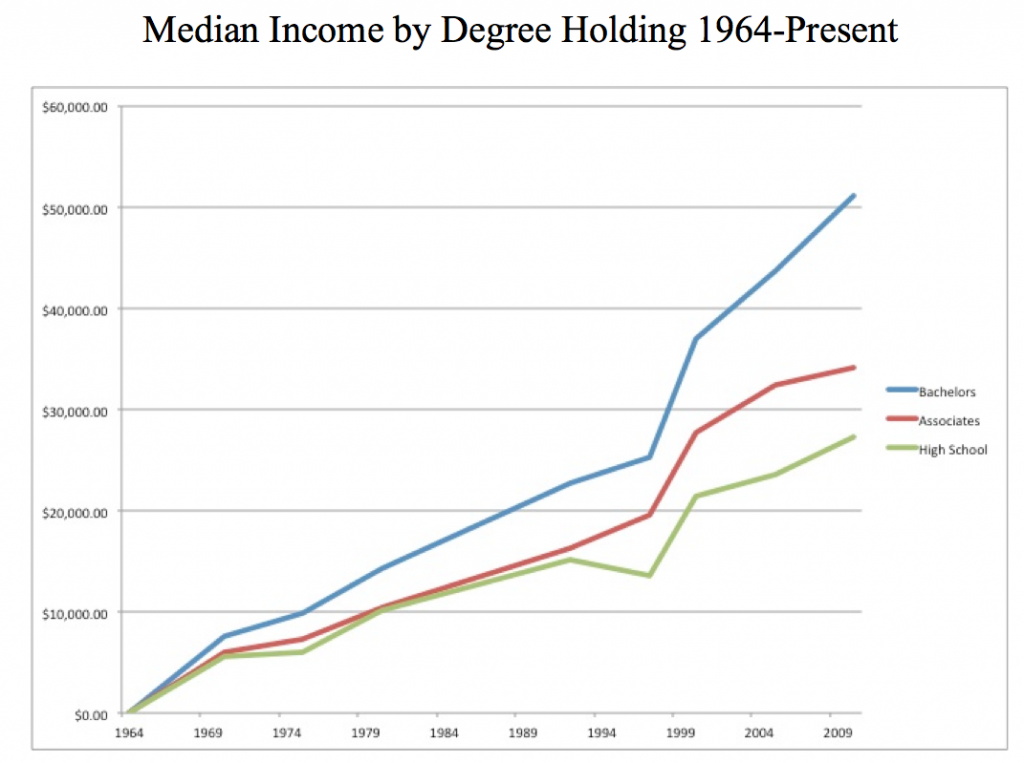

As previous projection statistics have shown, employment opportunity requiring a bachelor’s degree is growing. When examining this change over time from the 1960s to the present, Statistical Abstract Census data is representative of this phenomenon. It suggests that changes made from 1964 to 2010, including the increase in remedial course offerings, vocational education, and a reduction in humanities transfer courses has stagnated financial gains for associate degree completion.

Utilizing the median income figures by degree holding, a graph was constructed to highlight the occurrence of deteriorated economic growth by associate degree graduates. In 1970 the graph shows that the median income of a person holding an associates degree began to rise slightly above the income of a person who had only obtained a high school degree. By the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s the graph shows that there is little difference in the median incomes between persons with high school completion and associates degree. This clarifies that in the 1970s and 1980s there was little socio-economic mobility for community college students. 18

The graph illustrates a second important finding. It highlights the significant economic advantage of completing a baccalaureate degree. Today, the associate’s degree shows some economic advantage over a high school degree, but a bachelor’s holds twice that economic advantage. This would allow students to build income-producing assets. Pathways that allow for transfers opportunities to four-year institutions must be created in community colleges to assist in the socio-economic mobility of the students. Contradictory programs like vocational education contribute to the class reproduction of already disadvantaged populations.

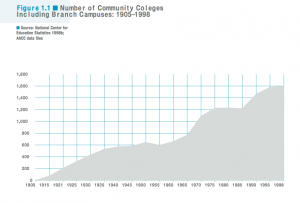

Despite the limited economic gains of completing an associate degree community college institutional expansion is still on the rise and enrollment continues to sore . According to Brint and Karabel, “by 1980, over 90 percent of the population was within commuting distance of one of the nations 900 community college.” 19 This growth shows a commitment to educational access and opportunity in America, although is commitment enough to improve the economic trajectory of community college students?

An assessment of the drastic changes community colleges have made over the last fifty years illustrates a story that is contradictory to the institutions popularity. This expository focuses on how community colleges act as an additional public institution, participating in the cycle of social class reproduction. Their offerings while extensive, divert resources and attention away from the best course for socio-economic mobility. Today only thirty percent of the students enrolled in community college will complete their degree in one hundred and fifty percent of the time required to finish an associate’s degree. 20 The open access has resulted in education for all and mobility for only a few.

- Beach, J. M. Gateway to Opportunity: A History of the Community College in the United States. Stylus Publishing, 2011. ↩

- Brint, Steven, and Jerome Karabel. The Diverted Dream: Community Colleges and the Promise of Educational Opportunity in America, 1900-1985. Oxford University Press, USA, 1991. ↩

- Brint, Steven, and Jerome Karabel. The Diverted Dream: Community Colleges and the Promise of Educational Opportunity in America, 1900-1985. Oxford University Press, USA, 1991. ↩

- Colleges, American Association of Community and Junior. American Association of American Community and Junior Colleges Assembly Report 1972. American Association of Community and Junior Colleges, April 1972. ↩

- Lombardi, John. “The Decline of Transfer Education. Topical Paper Number 70. – ERIC – ProQuest.” Report ED179273 (1979): 37. ↩

- “Complete College America”, 2011. http://www.completecollege.org/. ↩

- Brint, Steven, and Jerome Karabel. The Diverted Dream: Community Colleges and the Promise of Educational Opportunity in America, 1900-1985. Oxford University Press, USA, 1991. ↩

- Pincus, Fred. “The False Promises of Community College – Class Conflict and Vocational Education.” Harvard Educational Review 50, no. 3 (1980): 332–361. ↩

- Monaghan, Peter. “Educators Urged to Help Vocational Students at 2-Year Colleges Move on to Bachelor’s Degrees.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, April 12, 2001, sec. Archives. http://chronicle.com/article/Educators-Urged-to-Help/108231/. ↩

- “Complete College America”, 2011. http://www.completecollege.org/. ↩

- Beach, J. M. Gateway to Opportunity: A History of the Community College in the United States. Stylus Publishing, 2011. ↩

- “Connecticut Community College Course Search”, n.d. https://www.online.commnet.edu/pls/x/bzskfcls.P_CrseSearch. ↩

- Brint, Steven, and Jerome Karabel. The Diverted Dream: Community Colleges and the Promise of Educational Opportunity in America, 1900-1985. Oxford University Press, USA, 1991. ↩

- Bailey, Thomas, and Vanessa Smith Morest, eds. Defending the Community College Equity Agenda. 1st ed. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. ↩

- Dougherty, Kevin J. The Contradictory College: The Conflict Origins, Impacts, and Futures of the Community College (Suny Series in Frontiers in Education). State University of New York Press, 1994. ↩

- Claus, Jeff. “JSTOR: Curriculum Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Spring, 1990), Pp. 7-39.” Curriculum Inquiry 20, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 7–39. ↩

- Gonzalez, Jennifer. “Obama Praises Community Colleges Amid Doubts About His Commitment.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 10, 2010, sec. Government. http://chronicle.com/article/Obama-Praises-Community/124869/. ↩

- Division, Systems Support. “US Census Bureau The 2012 Statistical Abstract: Earlier Editions”, n.d. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/past_years.html. ↩

- Brint, Steven, and Jerome Karabel. The Diverted Dream: Community Colleges and the Promise of Educational Opportunity in America, 1900-1985. Oxford University Press, USA, 1991. ↩

- “Digest of Education Statistics, 2010”, n.d. http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_198.asp. ↩