When my twins were babies, I took a ton of pictures. Everywhere we went I had a camera or a device snapping photos of them. Whenever their birthday draws near, I pull out my photo box to reminisce on how sweet they were and to remind myself how far we have come. As the Sheff v. O’Neill victory approaches its seventeenth anniversary, I can’t help but wonder if the current snapshot of Hartford area schools has grown all that far from the picture of racial isolation and concentrated poverty we saw in 1996. From Project Concern in the 1960’s to Open Choice today, the battle to integrate Hartford area schools has been long and hard. According to the Sheff plaintiffs, the case was fought “ … to prepare all children to live and prosper in a growing racial/ethic, economically globally connected world” (“About Sheff v. O’Neill”). While some progress has been made, little has really been done to diversify the student populations of schools within Hartford public school region.

Just two years after the 1996 Sheff ruling, local school desegregation advocates presented a viable metro integration plan to “remedy” the grievances addressed in the case by mandating public school integration. According to “The Unexamined Remedy”, this involuntary integration was to occur by combining Hartford and twenty-one neighboring towns into a regional school district. Key constituents showed little to no support for this model. If true school integration is and was a priority for the State, why didn’t this happen? Hartford public schools have been ailing for decades. What factors caused education reformers of the time to turn their backs on a possible cure and relinquish the remedy?

A Lofty Goal: Sheff v. O’Neill 1996 Ruling

In April of 1989, a group of Hartford area students, their parents, and attorneys banded together to file a law suite against the city of Hartford. The State Board of Education and Governor at the time, William O’Neil, were listed as the defendants in the case. The suit was named after one of the plaintiffs, Elizabeth Horton Sheff. Sheff’s son, Milo, was a fourth grader in a Hartford public school at the time. According to the Sheff Movement, the case sought to “… redress the inequity between the level of education provided to students in Hartford public schools and that available to children in surrounding suburban districts” (“About Sheff v. O’Neill”). The plaintiffs claimed that the state had violated Hartford public school students’ constitutional right to equal educational opportunity under the Connecticut State Constitution, because they allowed schools to be racially, ethnically, and economically segregated.

In July of 1996 with a vote of four to three, The Connecticut State Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Sheff plaintiffs. The Court acknowledged that the State had not intentionally segregated the marginalized students within the Hartford public school system from their peers of other racial and ethnic backgrounds in neighboring towns. However, the Court did recognize that the State was responsible for the way school district boundary lines were drawn which caused Hartford public school students to be isolated from students of other racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds.

As for a course of action to address the racial, ethnic, and economic isolation of Hartford children, the court deemed that to be a matter for legislature and the executive branch. Furthermore, no time frame was given to enact any specific remedy.

Examining “The Unexamined Remedy”

In June 1998, The Connecticut Center for School Change, a statewide non-profit with the goal “to help all districts teach all students to achieve at high standards” (“Who We Are”), came up with a detailed integration plan. The proposal was co-authored by then executive director, Dr. Gordon Bruno, and an education policy political scientist, Dr. Kathryn McDermott. The report, referred to as “The Unexamined Remedy”, laid out a plan that would rapidly address the racial and economic isolation within Hartford and twenty-one surrounding towns. The very first sentence of the fifty-two page document states, “The intent of this document is to propose a means by which a high-quality, racially, and ethnically integrated education may be achieved for all Hartford area public school students” (The Unexamined Remedy 3). The plan provides a complicated, yet feasible course of action to integrate schools by consolidating school districts into a regional school system(s). The plan says that local communities in the state of Connecticut “tend to be racially and socioeconomically homogeneous” (The Unexamined Remedy 6). The report goes on to say that town lines in Connecticut separate communities by socioeconomic class. While integration is the primary goal of the plan, it is not the only goal. The focal point of The Unexamined Remedy is quality education for all students throughout the region. The plan states, “Educational excellence, equal educational opportunity and racial/ethnic integration are inseparably related” (The Unexamined Remedy 3). Gordon Bruno emphasized that integration does not automatically signal quality education. The plan explicitly defines what The Connecticut Center for School Change what quality schooling means to them.

The plan highlights smallness as being an essential element to quality schooling. They made very specific recommendations for school and class sizes suggesting smaller classes of no more than fifteen students for elementary school classrooms, eighteen is the limit for grades three through five, a maximum of twenty students per class were suggested for sixth through eighth graders, and a cap of twenty-five students was placed on grades nine through twelve classrooms. “Smallness increases the chances that all students are known well by teachers and administrators in their schools, both when they arrive as newcomers and throughout their school careers” (The Unexamined Remedy 6). According to the plan, small schools and small classrooms would build the relationships necessary to foster academic success, especially for students with special learning needs.

In addition to smallness, the plan makes other strong recommendations for achieving school quality. They advocate for pre-schools for all parents of three and four year olds who desire them as well as extended day kindergarten programming in every elementary school. It opposes tracking citing the negative affects it tends to have on minority students, “For too many minority students, incorrect assignment to low or special education tracks becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy” (The Unexamined Remedy 7). Individual learning plans were advised to ensure every child’s needs are met.

These initiatives are deemed to be integral to the production of quality education alongside the initiative to integrate. Quality indicators as they are called include small schools, small classes, school readiness, alternative programs, individual learning plans, accountability for standards and learning goals, character development, community service, and conflict resolution training. Per the Connecticut Center for School Change, without the aforementioned the ultimate goal of Sheff, access to quality education for all, would be inconceivable.

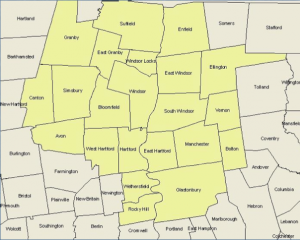

The twenty-two towns considered for participation in the regional district consolidation plan were the communities previously required to “… engage in regional planning to enhance educational quality and diversity” (The Unexamined Remedy 4) by the General Assembly in 1994. The twenty-two towns were Avon, Bloomfield, Bolton, Canton, East Granby, East Hartford, East Windsor, Ellington, Enfield, Glastonbury, Granby, Hartford, Manchester, Rocky Hill, Simsbury, South Windsor, Suffield, Vernon, West Hartford, Wethersfield, Windsor Locks, and Windsor (The Unexamined Remedy 4). While these towns were proposed, The Connecticut Center for School Change was open to other recommendations for groupings. Of this, the plan states, “A different grouping of municipalities may work better than the one we propose; in addition, it may make sense to create more than one consolidated district in the area, reflecting natural boundaries or existing relationships among communities” (The Unexamined Remedy 4).

Regardless of the towns involved, the metro integration plan would have required some drastic changes in school governance. Each of the twenty-two towns has its own local school board. The proposal recommended replacing these local school boards with a regional one to ensure that town priorities would not be placed over the regional agenda. Also, reducing the administrative overhead of twenty-two school systems would have freed up money that could go directly to increasing the funding of individual schools.

The proposed regional school board would have consisted of thirty-one members. Twenty-two of them would have been representatives of the individual towns, and there would have been nine additional. School boards typically do not exceed nine members. The plan proposed a board over three times that. The Connecticut Center for School Change notes that smaller school boards were initially created to give elite members of society to greater control over schooling. The plan rejected small school boards, because they wanted to give all communities a say in school governance. In the proposed plan, The Connecticut Center for School Change would simultaneously create a large centralized school board and small locally controlled schools. A regional school district would have meant school level decision making over things like curriculum and budget, but adherence to district-wide standards and policies. The plan gave a lot of agency to local schools to operate effectively within district guidelines.

Parents also had a great deal of agency, or controlled choice, as it was called. The intent was to make all schools magnets. Parents would apply to several schools they would like for their children to attend. Unlike the current school lottery system, parents would have been guaranteed that their children would be placed in one of their selections. There would be a variety of options and all schools would be of good quality.

Relinquishing the Remedy: Why Didn’t This Happen?

At the time of the report in 1998, there were 172 public schools within the proposed district. It is difficult to get groups within a single district to agree on a course of action. Bringing several districts with varying demographics together presented many obstacles.

Such large and small changes are usually met with resistance. According to Gordon Bruno, the metro integration plan was opposed by many and elected officials refused to consider it because of concerns about getting support for re-election. Bruno also names the Connecticut Parent Teacher Association (CTPTA) for being in direct opposition to the plan. He does note that the CTPTA’s opposition would not be directly towards integration, but the consequences of school district reduction. Consolidation of school districts would mean a reduction in school board members. In a 2004 interview, Dr. Bruno says that the ranks of superintendents would have been reduced from over one hundred and seventy to about a dozen (Bruno 6). Career displacement for high-ranking educators was incredibly controversial. Those controversies ultimately lead to political pressure. Dr. Bruno recalled that a number of constituents agreed with the plan behind closed doors, but none were willing to face the political backlash by publicly supporting the plan. According to Dr. Bruno, the plan was the right thing to do for the students, but the wrong approach for political interests.

Dr. Bruno and Dr. McDermott’s may very well have been too radical in their suggestions for integration for serious consideration in the “land of steady habits”. Attorney and former education committee chair, Cameron Staples, notes that Connecticut has a long history of local school control. He believes the plan was too extreme and doesn’t recall anyone supporting it besides the authors. He goes on to say that a shift from local to regional consolidation may have been viewed by suburban constituents as a way to disperse the issues of Hartford public schools to the suburbs (Staples 2).

There was opposition to this progressive plan that stemmed from fears of forced integration. Of school integration, Dr. Bruno says that it is “both right and required” (Bruno 4). He did not believe that voluntary integration would yield results.

Some may assume that urban parents were desperate to integrate schools and give their children ‘better opportunities’. Co-author, Kathy McDermott points out that the threat of forced integration was something that both urban and suburban parents feared. She asserts, “City people are just like suburban people and generally like the idea of having their kids right around the corner …” (McDermott 2). Politicians were leery of telling people where to send their children, particularly when that may mean long commutes between districts.

Although admirable in its approach, the metro integration plan did not happened. There were several factors that prevented the plan from becoming reality. The logistics of governing and details like transportation coupled with a genuine fear of change and the unknown prevented the plan from garnering real support. When Dr. Bruno retired from The Connecticut Center for School Change, The Unexamined Remedy retired with him (McDermott 4). The remedy was indeed examined, but tossed aside for more politically friendly approaches. The school district boundary lines have remained intact, and the families that choose to integrate have found other means of doing so through choice programs and magnet schools.

References

“About Sheff v. O’Neill.” Sheff Movement. Web. 5 April 2013. <http://www.sheffmovement.org/aboutsheffvoneill.shtml>

Bruno, Gordon. Interview with Jennifer Williams. The Unexamined Remedy Metropolitan School District Oral History. Hartford, 2004.

McDermott, Kathryn. Interview with Jennifer Williams. The Unexamined Remedy Metropolitan School District Oral History. Hartford, 2004.

“Memorandum of Decision – 3/3/99.” Connecticut Judicial Branch. Web. 1 May 2013. <http://www.jud.ct.gov/external/news/sheff.htm>

“About This Website.” Smart Choices. Web. 1 May 2013. <http://caribou.cc.trincoll.edu/depts_educ/smartchoices/about.html>

Staples, Cameron. Interview with Jennifer Williams. The Unexamined Remedy Metropolitan School District Oral History. Hartford, 2004.

The Connecticut Center for School Change. The Unexamined Remedy. 1998. PDF file.

“Who We Are.” The Connecticut Center for School Change. Web. 5 April 2013. <http://www.ctschoolchange.org/who-we-are/>

Williams, Jennifer. “The Unthinkable Remedy: The Proposed Metropolitan Hartford School District”. Presentation for the Cities Suburbs Schools Project at Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, Summer 2004.