Since the 1990s, there has been an increasing focus on special education due to the American Disabilities Act being passed. The change over time in prioritizing equal access and accommodations has led to new forms of assistive technology being created to aid people both in and outside of the classroom. Some of the technological innovations come in the form of smartboards, Ipads, clickers, computers, and special keyboards. On these platforms, apps have been created with new fonts, games, videos, and communication tools to help people with special needs learn in a new fashion. Some critiques of these programs emerged due to the lack of human interaction that may occur, and that may hinder the social aspects that the educational system provides for students with a disability–mental, physical, emotional, etc. Larry Cuban is a researcher who investigates the impact of technology on the educational system. He inspects whether technology altered classrooms live up to the promises that the new systems guarantee in the educational system over time. My research presents information about assistive technological programs in the special education system: although historian Larry Cuban has questioned whether technology changes classroom teaching and learning, has assistive technology for students with special needs been an exception to this rule over time?

I argue that assistive technological programs are beneficial in special education classrooms when the programs are intertwined into the normal classroom routine overtime. If introduced at once, it may cause a sensory overload for the students which may reduce the effectiveness of the assistive program. This may also decrease the human interaction too quickly and negatively affect the socialization of the students with adult leaders and fellow peers. However, there are benefits to the introduction of assistive technology programs in special education classroom which is why they should still be introduced to the daily learning process in the classroom. Advancements in technology have increased over time with faster processors and more interactive programs, and lots of promises have been made about how beneficial the ‘progress’ will be. Cuban delves into the truth about how reliable the beneficial promises about implementing technology into the classroom actually are. By examining multiple sources such as written works by Larry Cuban, blogs, and scholarly articles, this paper will address both how assistive technology has been implemented in special education classrooms over time and how effective the programs implementations are.

The introduction of technology into classrooms in more recent years has been a process that has been critiqued by people concerned that technology will lessen the learning experience. The introduction of computers to schools “as an instructional tool has been preceded by enormous publicity and speculation, obscuring many of the substantive issues surrounding its real and potential uses” (Howell, 1). Many educators and parents are anxious about computers being implemented into any classroom because of the little evidence of the beneficial qualities of computers with furthering education that was initially available. However, even as research has been done on the introduction of technology into schools, “the general findings of which are a sober reminder of how difficult it is to translate innovation of any kind into practice” even when “important observational and naturalistic studies have been conducted” (Rieth and Woodward, 1). Essentially, a point that researchers are trying to make to people who are wary of these implementations is that new systems of doing things has always taken time to adjust to. This can be applied to educational systems as well as ways of cleaning or communicating. The intensity of speculators has been even greater with implementations of technology to special education classrooms because there needs to be a lot of individualization into the programs.

Multiple forms of technology have been introduced into the classroom, starting in the 1970s and, in the 1990s—the programs became more advanced. One form of technology—that this paper focuses on—is assistive technology which “employs various types of services and devices designed to help people with disabilities function within their environment” (Blackhurst, 2). Assistive technology for people with special needs is comprised of different strategies, devices—mechanical or not—that may be specialized to a certain disability, aids, etcetera that “(a) assist them in learning, (b) make the environment more accessible, (c) enable them to compete in the workplace, (d) enhance their independence, or (e) otherwise improve their quality of life” (Blackhurst, 2). However, a common critique of the goal of assistive technology in classrooms is that the use of the technological devices “should lead to cognitive gains that are superior to traditional instructional methods” (Woodward and Cuban, 6). This claim works to discredit teachers of the vital work that they do for the students. Emphasis of the word ‘should’ in the quote highlights that the introduction of technology is not perfect; there is trial and error with the implementation of new teaching techniques and technology—especially in the classroom. Because of this, researches argue that assistive technology “must also be used in combination” with other teaching devices and methods (Blackhurst, 4). Also, the programs are more beneficial to the learning process when they are introduced over time so that there is time and space to tweak the different forms of assistive technology to best aid the students and teachers.

Furthermore, the introduction of computers into special education classrooms over time as assistive technology has had both a positive and negative response. There can be some more personalization within the programming of computers to the individual student which can help with them learning at the specific pace that is most beneficial to them:

“Likewise for special-needs students, who find learning via e-readers, computers and software to be more engaging. And because lessons through such devices can be personalized for the students rather than a single lesson for the whole class, children with learning disabilities find themselves able to handle even advanced lessons and reach their fullest potential” (n.a., 1).

For many, this is an added draw to adding assistive technology into the classroom. The ability to manipulate the technology has not always been a factor in assistive programs. For example, when braille was introduced in 1829, everyone who used it had to learn it and apply it in the same manner which made a beneficial advancement less applicable and helpful. For this reason, “the setting factors that determine when and where computers will be used in the classroom, including their location, scheduling, and patterns of usage among students and teachers” are vital components to implementing assistive technological programs in special education classrooms (Howell, 1). A lot can be learned from older implementations of programs for people with special needs that guided introducing new programs in the past forty years.

An important timeline in the implementation of technology that lead to the introduction of the computer and other devices. Beginning in the 1970s, “attempts to summarize the effectiveness of technology in special education” began appearing due to the beginning stages of microcomputers (Woodward and Cuban, 5). The device continued to be created and became mass produced in the 1980s and is considered to be “the most influential technology of the late 20th century” (Blackhurst, 1). The microcomputer became a template for more modern forms of computers and tablets and their implications into the classroom today. Yet, the microcomputers were not introduced to teachers or students individually because “the 1980s also witnessed an increased emphasis on assistive technologies and the emergence of technology literature and computer software targeted directly at special education” (Blackhurst, 1). From this overdose of technology, researchers found that negative responses to assistive technology appeared at a heightened rate. Parents and teachers were wary “that technology’s primary use was to teach content material or basic skills; that is, in those studies, technology was used as an electronic tutor” (Woodward and Cuban, 5). For special education classrooms in particular, this posed a major concern about losing the individualized approach that comes from Individualized Education Plans (IEP) and teacher-student interactions. The goal of assistive technology, as seen earlier, is not to act as a tutor, but to make the daily life of a person with a disability easier and more accessible. In the classroom, the technology also helps to provide equal access for all students in the building, even if environmental factors vary. The late 1980s also had legislation being passed—the Technology-Related Assistance for Individuals with Disabilities Act—where Congress said that technology is beneficial for people with disabilities and should be allowed/accommodated for. Thus, the 1980s served as a transition period into the 1990s in terms of awareness and computer advancements.

Once the American Disabilities Act (ADA) passed in 1990, there was an increased focus on special education classrooms. With the ADA, a shift about the function of assistive technology occurred: “the remedial and special education literature abounds with a number of effective interventions, such as direct instruction, peer tutoring, and cooperative learning” (Woodward and Cuban, 6). The transition in perception around assistive technology use in special education classrooms suggests that teachers and parents are fining success in the alterations of the technology as it develops overtime. Plus, at this point in time, computers were starting to be seen more in the classroom on a regular basis; in fact, in a survey about technology use, “all of the special education teachers surveyed thought learning about computers was important and thought computers should be used in subjects other than math” (Elkins, 3). Not only is there a shift in the effectiveness of technology in the classroom, but teachers are also becoming more aware and versed in the different applications of the programs to most benefit the students. Cuban notes this “as a modest shift in the spectrum from non-users to occasional users and from occasional users to serious ones,” and he accounts this to the ADA being passed in 1990 and a heightened drive in teachers to explore ways of greater inclusion (Woodward and Cuban, 122). Also, the “focus on instructional design variables” around this time helped in “identifying the impact of critical instructional variables” on “potentially significant implications because these features could be added to or subtracted” to programs for students with disabilities (Woodward and Cuban, 8). The design variables are a step towards solving the problem around assistive technology with needing individualized plans for the students in special education classrooms to align with their IEPs.

Today—the early 2000s—is a technology centered world, but there are still concerns around technology being used in special education classrooms. Many parents are concerned that there is too great a dependence on technology in schools as some transition from textbooks to computers and Ipads. This is a positive in a sense for students who use keyboards to communicate—sometimes seen with students on the Autism Spectrum—because it lessens the emphasis on the student using something that signifies them as ‘different’. Yet, a key point to emphasize is that “the ultimate decision as to how or whether they will be used is left generally to the individual teachers” (Elkins, 1). Different attitudes toward teaching with technology generally relate to “teacher attitudes toward computing, [and] therefore, are critical if computer are to be successfully implemented in special education classes” (Elkins, 1). This discussion relates back to the transition in the number of teachers moving towards technology-based learning back in the late 1990s. Some teachers use “videodisc programs…with an entire class of students” to teach the general lesson, and then work individually with the students to work through remaining questions about the overall learning goal (Woodward and Cuban, 11). A rebuttal to this program—using technology only as a general introduction and not for the students—is that some applications are actually better for teacher organization and allow for the programming to be individualized for each student if they log into an account:

“Applications such as Google Classroom help teachers stay better organized and connected with their class while also tracking a student’s academic progress. This has helped to yield critical information regarding the learning process and performance of special-needs students, and subsequently, teachers can create more customized lesson plans for those students as well as determine how technological devices and software applications can better be used to assist them in their instruction” (n.a., 1).

However, the knowledge that this is not a unanimous practice emphasizes that “new technologies will not be easily integrated without a more definitive understanding of the interactional context into which they are being introduced” (Howell, 1). Instead, many people emphasize that the individual student matters more in the education process than the actual implementation into the program. Also, the setting of the classroom being a communitive place actually allows assistive technology to be a segway for more complex forms of reasoning because there can be collaboration with the other students in the classroom (Howell, 1). Therefore, the current debates around the implementation of assistive technology in special education classrooms is still fairly similar in the major conflicts that the discussion faces. Yet, with computers and programs, the installment of updates lets technology update to the newest version each second meaning that the newest programs are slowly upgrading to allow teachers and students time to get comfortable with assistive programs.

Overall, the use of assistive technology in special education classrooms is still widely debated today because of the potential lack in individualization and the lack of systematization across education systems. If teachers use technology in the forms of keyboards for communication, individualized apps for interactive learning, and smartboards with clickers for whole-class discussion, then there may be success with the programs. Yet, they must be introduced and advanced in increments to the classroom because they could inhibit socialization and communication techniques if used too quickly. In the past forty or so years, teachers and researchers have worked to improve the introduction techniques of assistive technology, especially after the ADA. Larry Cuban’s research on the effects of technology in the classroom are challenged by the use in special education classrooms due to the emphasis on one-on-one interactions between the student and teacher or aid. Moreover, the research around assistive technology in special education classrooms complicates the introduction of general technology because the purpose around assistive technology is slightly more geared to advancing skills that me need more fine-tuning for students with disabilities than students who are not in the special education classroom. Therefore, if assistive technology is integrated into special education classrooms in conjunction with standard classroom techniques and works to individualize programs based on student needs, then it is beneficial for the learning process and teaching practices in special education classrooms.

For a helpful infographic, follow this link:

Works Cited

50th-Anniversary-Timeline.Pdf. https://csd.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/607/2017/06/50th-Anniversary-Timeline.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr. 2019.

“Assistive Technology for Students with Disabilities.” The Tech Edvocate, 21 Nov. 2016, https://www.thetechedvocate.org/assistive-technology-students-disabilities/.

Blackhurst, A. Edward. “Perspectives on Applications of Technology in the Field of Learning Disabilities.” Learning Disability Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 2, 2005, pp. 175–78. JSTOR, JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1593622.

Elkins, Ruth. “Attitudes of Special Education Personnel Toward Computers.” Educational Technology, vol. 25, no. 7, 1985, pp. 31–34. JSTOR.

Howell, Richard D. “Technology and Change in Special Education: An Interactional Perspective.” Theory Into Practice, vol. 29, no. 4, 1990, pp. 276–82. JSTOR.

Woodward, John, and Larry Cuban. Technology, Curriculum, and Professional Development: Adapting Schools to Meet the Needs of Students With Disabilities. Corwin Press, 2001.

Woodward, John, and Herbert Rieth. “A Historical Review of Technology Research in Special Education.” Review of Educational Research, vol. 67, no. 4, Dec. 1997, pp. 503–36. SAGE Journals, doi:10.3102/00346543067004503.

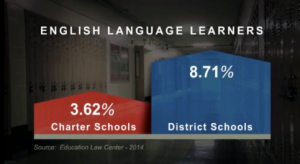

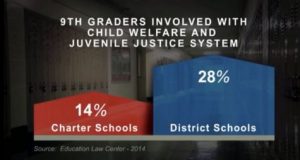

(Mondale, Backpack Full of Cash, 0:20)

(Mondale, Backpack Full of Cash, 0:20)