“Teach for America Welcomes and seeks out rigorous independent evaluations as a means of measuring our impact and continuously improving our program.”

Six years ago, on October 5th, 2006, this quote appeared on the Teach For America website promoting the importance of continuous improvement and change in order to ensure the maximum efficiency of this still developing program. Today, six years later, hard evidence and research is entirely omitted from the website with the emphasis on personal testimonies of corps members and inspirational quotes and statements. This pattern is not solely apparent within the Teach for America (TFA) website, it is also apparent among multiple different studies conducted over time among TFA advocates. Beginning in the early 1990’s, the first evidence reflecting the impacts of Teach for America began to be produced by scholars and TFA advocates. Multiple criticisms appeared, ranging from inadequate training of corps members prior to their placements to a lack of improvement on reading scores in the classrooms. However, improvements were acknowledgeable, specifically in regards to math due to the statistically significant positive impact TFA corps members had on students’ math scores. Continuing through the early 2000’s, studies and advocates continued to analyze TFA based on statistics; however, results were beginning to appear negative than the beginning years of the program. Recently, a drastic shift in scholarly articles, mainly from former TFA members or advocates of TFA, analyzing the effectiveness of TFA has begun to occur. Five years ago, TFA advocates emphasized and encouraged reform in response to numerous scholarly studies evaluating the statistical impact of the program, but present-day materials from advocates focus on testimonials and inspirational quotes instead. This change over time on the part of advocates is due to the difficulty in providing a reliable nation-wide statistical evaluation of TFA, whereas anecdotal evidence is concrete and unequivocal.

TFA, only a twenty-two year old program, originated in 1989 at Princeton University when Wendy Kopp wrote her senior thesis on the achievement gap in America. She was determined to create a program that would help to bridge this gap and provide students with the quality teachers they deserved from some of the most elite universities in the country. She was initially faced with the difficulty of receiving adequate funding to support her new endeavor but with a $500,000 grant from H. Ross Perot, Kopp’s hopes to create an impact through a revolutionary program quickly became a reality. TFA began in 1990, a year after Kopp’s graduation from Princeton, with a small group of 500 corps members. These members underwent training at the Los Angeles summer institute prior to being placed in their schools. TFA initially began as a small-scale grassroots organization educating 35,000 students across six different regions in the United States. Remarkably, the most recent data from 2010 shows that TFA now consists of 8,200 corps members who are educating over 500,000 students (Teach for America: A Timeline, 2011). In addition to TFA’s drastic expansion within the United States, in 2007 Kopp launched Teach For All in order “to support development of [the Teach For America] model in other countries” (TFA Website, 2012).

One of the most influential changes, in regards to advocates of TFA, that has occurred over the past half a decade is mainly notable through the evaluation of the TFA website. In 2006, as stated above, the TFA website clearly encouraged outside scholars to conduct research and provide feedback in regards to the progress of the program:

In 2006, a study conducted by Decker, Mayer, & Glazerman (2004), was advertised proudly on the TFA website, as shown in the screenshot above, to indicate the gains they had made in regards to math score achievement. This study was a national evaluation of TFA, based on the Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, New Orleans, and Mississippi regions. This national study provided a comparison of control group teachers and TFA teachers. Control group teachers referred to any teachers that had no affiliation with TFA and TFA teachers referred to TFA corps members still participating in their first two years of teaching required by TFA and former corps members that were still teaching despite their completion of their two required years. It was concluded that “about 25 percent of TFA teachers had either a bachelor’s or a master’s degree in education compared with 55 percent of control group teachers overall” (Decker et al., 2004). Similarly, 51 percent of TFA teachers had earned their teacher certification whereas 67 percent of the control group had earned their teacher certification.

Even with this discrepancy in certification and achievement levels in schooling towards degrees involving education among TFA teachers and control teachers, Decker et al. found that TFA teachers still had a statistically significant positive impact on their students in regards to achievement on math scores but not in regards to reading scores. The graph below represents this relationship shown in Decker et al.’s study:

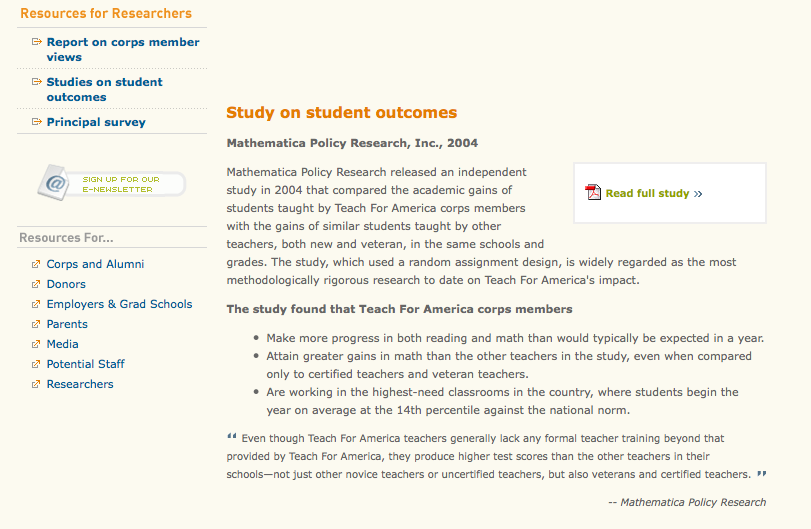

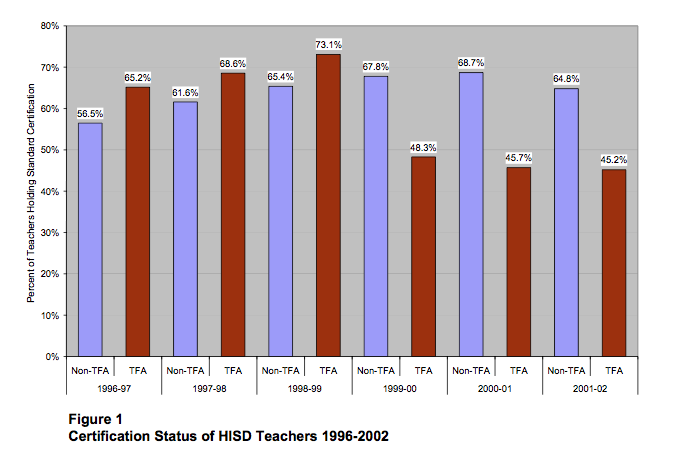

Similarly, a study conducted in 2005 by Darling-Hammond, Holtzman, Gatlin, & Heilig provided an excellent statistical analysis of the impacts TFA has had based on a large sample of students from Houston Texas. The study compared TFA corps members to certified teachers with similar amounts of experience from 1995-2002. As stated earlier, all TFA members underwent a brief training period prior to entering their schools, but many have not participated in state certification programs that can take years to complete. This study examines the differences between TFA members with their teacher certification, TFA members without their teacher certification, teachers in the Houston school systems that were not TFA members with their certification, and Houston teachers that had not received their teacher certification.

It was found that from 1996-1999 there were significantly more certified TFA members than certified non-TFA members, however, from the 1999-2000 school year and on, this relationship was completely reversed and significantly more non-TFA members were certified than TFA members (Darling-Hammond et al., 2005). This relationship can be shown by the graph below:

This decrease in the certification of TFA corps members over time has caused an overall negative effect on the program in Houston. In the earlier years of this study, when TFA members were more likely to be certified than Houston teachers that were not TFA members, the impact of their teaching was positive, specifically in regards to the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS) math test. However, in the early 2000’s, when the number of certified TFA members declined, the impacts were found to be non-significant, or even negative, in regards to improvements on scores (Darling-Hammond et al., 2005).

In response to this data, the TFA website intelligently chose to advertise the positive outcomes resulting from these studies when declaring, in regards to Decker et al.’s study that TFA teacher’s students “attain greater gains in math than other teachers in the study, even when compared only to certified teachers and veteran teachers” (TFA Website). However, advocates are not seeking to ignore the other statistics, especially when articles have been written by TFA advocates proposing reform and improvement to the flaws emerging from scholarly studies. In 2008, Hopkins, a former TFA corps member, wrote an article in response to data from earlier studies on TFA. Due to concrete statistics in regards to what was beneficial for the program and what was detrimental, Hopkins was able to suggest reform efforts to TFA that could have the potential to make a significant impact on improving an incredibly promising program. She suggests three alterations, “1) extend the TFA commitment to three years; 2) convert that first year of teaching to a residency training year, offering classroom training with expert veteran teachers while corps members also complete coursework toward certification; and 3) offer incentives for corps members to teach longer than three years” (Hopkins, 721). These suggested reforms may not be the only answer, but they were an attempt by a dedicated former member of TFA to address some of the more prominent issues the program struggles with and are challenged on by critics.

The acknowledgement of numerical analysis provided by studies over a decade after the implementation of TFA, by advocates, allowed for the hope of incredibly beneficial reform to this still developing program. The data produced in the early to mid 2000’s suggested both positive and negative impacts the program had made on school systems and both former corps members and employees of TFA were receptive to this data and willing to publicly advertise it. Recently, in the past few years, advocates of TFA have taken a different approach, eliminating the focus on statistical research and relying heavily on testimonial evidence.

Studies from 2011 and 2012 impeccably mirror the more recent changes to the TFA website over the past six years. As shown through Decker et al.’s study, statistics in regards to mathematics scores are in favor of TFA, however, TFA has made little to no impact on reading scores. Also, Darling-Hammond et al. provides evidence that the statistics favoring TFA are slowly declining over time. More recent studies have chosen to avoid these findings and instead propose testimonial explanations for TFA’s success, mainly due to the contradictory statistics produced at local and national levels in regards to the effects of TFA.

The most notable change, since 2006, occurred within the TFA website. Six years ago clearly on the bottom of the web site appeared the link “researchers”:

Today there are still similar links such as, “how to apply” and “donate” but instead of options to view research there are links such as “where we work,” due to the expansion of the program and the numerous site options, and “committed individuals” among others. One of the first images seen when entering the website is, “What Role Will You Play?” with the caption below the question stating, “We know it’s possible to provide a great education for all kids. Hear from corps members who are leading their students to success.” The website has shifted from promoting and advertising the program in a fact based manner to utilizing, as said before, personal testimonies that evoke emotion and inspiration among possible future participants.

This shift over time has been reflected not solely on the TFA website but also among studies written in the past two years by other advocates of TFA. These studies claim that “more influential in the policy world are the anecdotal stories surrounding TFA, which range from portrayals of dismal schools where TFA teachers worked diligently in the interests of oppressed youth (e.g., Foote, 2008; Johnston, 2002), to testimonials supporting TFA’s impact on students’ lives” (Téllez, 2011). Téllez presents an entire case study based on “Stephen,” a pseudonym for a former corps member, and his story of entering education, his TFA experience, and his continued path in the field of education after TFA. Téllez claims that studies like Stephen’s “could help to move us past the indeterminacies of the quantitative research as well as providing a more objective analysis of TFA than the descriptive literature” (Téllez, 2011). As Stephen has continued on to become the principle of an Urban Charter school, his personal testimony emphasizes that TFA’s undeniable support and optimistic outlook on his ability to make a difference among his students at his placement school is what led him to succeed. He would not have gained motivation from observing favorable statistics for TFA. He gained confidence in his abilities from the support and belief instilled in him by TFA members and Téllez’s study seeks to portray that same message through his qualitative study.

Initially, with the emergence of Teach for America, advocates were eager to publicize and view statistics in regards to the impact of the program. These findings, on a local and national level, produced analogous data in some respects but with such an expanding program and many confounding variables it was found that it is hard to evaluate the impact of the program accurately. Therefore, a shift in present day materials produced by TFA advocates has occurred in order to avoid the ambiguity of certain statistics. The statistical data should not be ignored and is worth acknowledging and considering for the proposal of improvements to the growing program, but analysis of testimonies and promotion of these personal achievements is an effective and precise portrayal of the program and the impact it is making on its members as well as their students.

Resources:

Darling-Hammond, L. “Does Teacher Preparation Matter? Evidence About Teacher Certification, Teach for America, and Teacher Effectiveness Linda Darling-Hammond, Deborah J. Holtzman, Su Jin Gatlin, and Julian Vasquez Heilig.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 13, no. 42 (2005): 2.

Decker, P. T, D. P Mayer, S. Glazerman, and University of Wisconsin–Madison. Institute for Research on Poverty. The Effects of Teach for America on Students: Findings from a National Evaluation. University of Wisconsin–Madison, Institute for Research on Poverty, 2004.

“Home”, n.d. http://www.teachforamerica.org/.

Hopkins, Megan. “Training The Next Teachers For America: A Proposal for Reconceptualizing Teach for America.” Phi Delta Kappan 89, no. 10 (June 2008): 721–725.

“Teach for America: A Timeline.” Education Week 30, no. 24 (March 16, 2011): 24.

“Teach For America – Home”, October 5, 2006.

Téllez, Kip. “A Case Study of a Career in Education That Began with ‘Teach for America’.” Teaching Education 22, no. 1 (2011): 15–38.