Sonification of Harmonic Signals in the Brain

Therapies for cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients associated with chemotherapy: A meta analysis

The role of empathy, clinical traits, and eye gaze in contagious yawning and itching

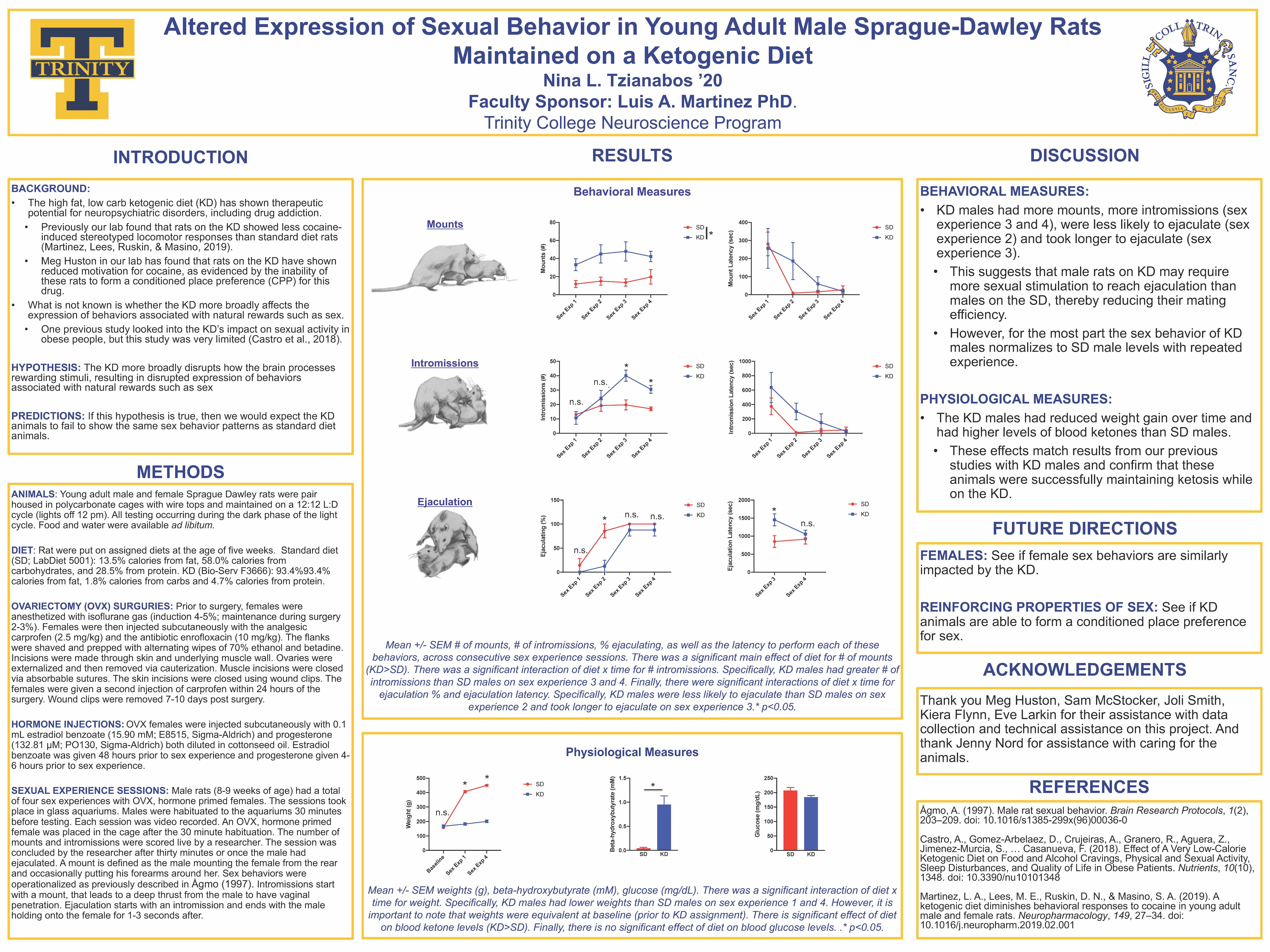

Altered Expression of Sexual Behavior in Young Adult Male Sprague-Dawley Rats Maintained on a Ketogenic Diet

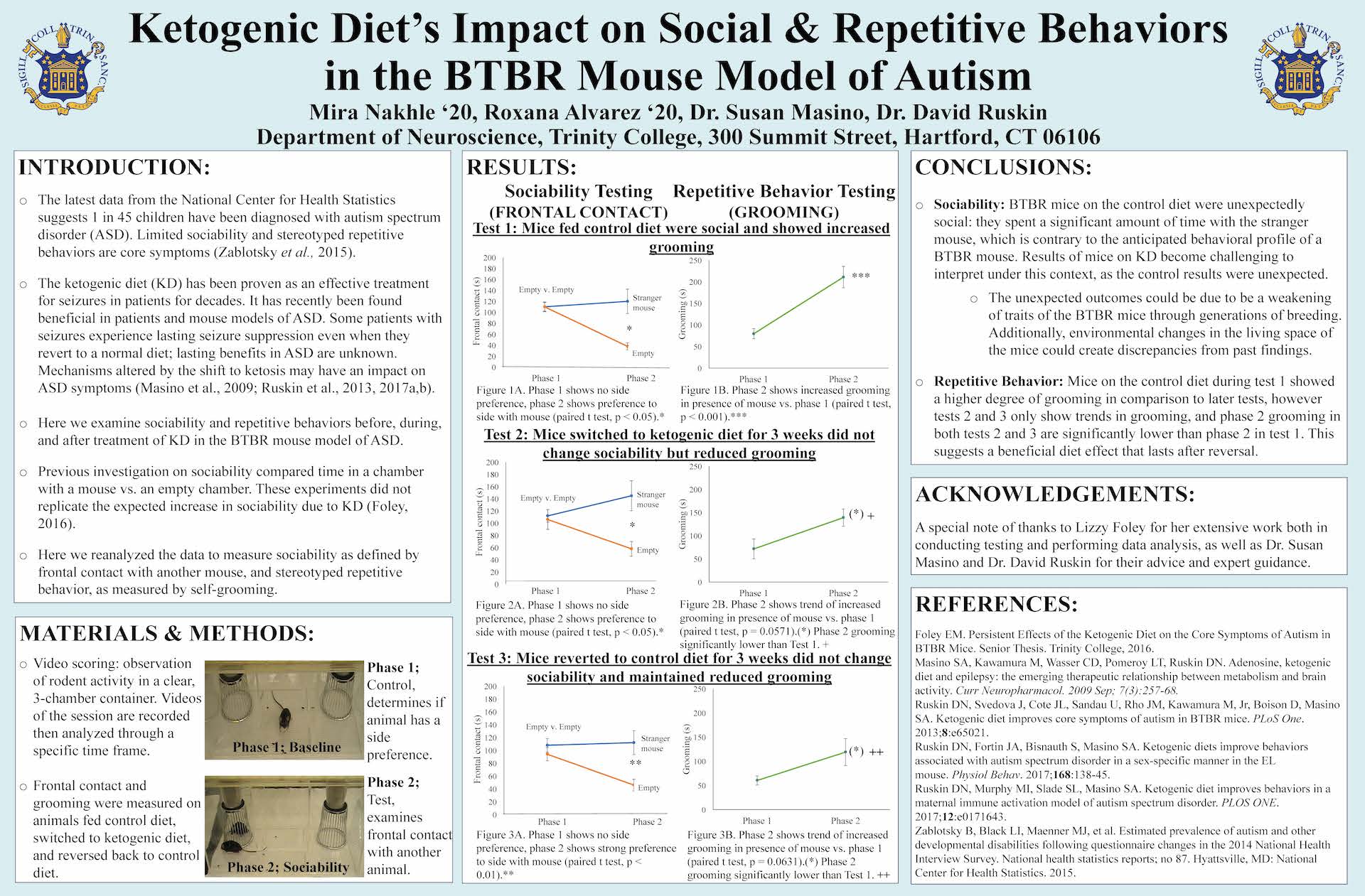

Ketogenic Diet’s Impact on Social & Repetitive Behaviors in the BTBR Mouse Model of Autism

Your friend has alcohol poisoning

Amanda Scopelliti

She was a tall, hazel-eyed brunette, a few years older, who had grown up in the same town as me. She lived on a street right by the high school and danced at my studio all the way through graduation. Then, she went off to college to continue her education and was found unresponsive in her dorm room after a night of partying. The paramedics pronounced her DOA: Dead on Arrival. The autopsy revealed that she had died from alcohol poisoning.

It’s no secret that college students all across America drink alcohol, but it’s important to be mindful that this substance is incredibly dangerous when consumed in excess and especially when combined with other psychoactive substances. It is estimated that about 1,825 U.S. college students die from alcohol-related injuries each year, and alcohol consumption is associated with lower college grades in addition to higher rates of on-campus sexual assaults, suicide attempts, and arrests. Furthermore, it has been found that students who binge drink are more likely to participate in unsafe sex habits, and a large number of American college students report being assaulted by a peer who was under the influence of alcohol (approximately 696,000 reports annually).

It’s important to be mindful that women are more vulnerable to alcohol poisoning than men, and symptoms include a loss of coordination, disorientation, hypothermia that causes clammy hands and bluish skin, repeated vomiting, passing out, slow or irregular breathing, seizures, being conscious but unresponsive, and coma. It is advised that you seek medical attention if you observe these symptoms in another individual, especially because alcohol poisoning can be fatal.

Additionally, there are several things than you can do to help a friend who has alcohol poisoning. You should stay with them and keep them conscious, warm (sine hypothermia can result from alcohol poisoning), hydrated with water. You should monitor their symptoms, and if they fall asleep, it’s important that you ensure that they’re on their side so that they don’t choke on their own vomit. I’ve heard people suggest that you put a backpack on their back so that they are unable to roll over in their sleep. Unfortunately, choking on vomit is just one of the complications that can result from alcohol poisoning, and other complications include being severe dehydration that results in permanent brain damage and developing an irregular heartbeat, which can eventually stop.

Furthermore, long-term excessive alcohol consumption has been shown to have devastating effects on the brain, causing serious neurological problems and permanent brain. Individuals with an alcohol use disorder often have a poor diet that results in malnourishment. This can cause a vitamin B1 deficiency because alcohol prevents the body from absorbing the vitamin. A lack of B1 may result in brain damage after heavy drinking over an extended period of time. One condition that can result is called Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome, which consists of two different forms of dementia and causes symptoms such as paralysis of the eye muscles, loss of coordination, and difficulty learning. An additional complication that is sometimes caused by heavy drinking is called hepatic encephalopathy, and symptoms consist of a shortened attention span, depression, anxiety, and impaired coordination. The disorder results from alcohol causing inflammation to the liver, which is the organ responsible for filtering out toxins. An impaired liver can cause a buildup of toxins in the brain and lead to the unpleasant symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy.

Link Between Sleep and Fear

Madison Gilbertson

Could there possibly be a link between the amount of sleep we receive at night and our reaction to fear? An article by Michael Y. Park in Live Science entitled “Scared? Your Sleep Quality Could Be to Blame” looks at this very question. The article focuses most specifically on Rapid Eye Movement sleep, commonly known as REM. There are several stages of sleep. Stages one, two and three are included in what is call non-REM sleep and the last stage is REM sleep. Park discusses evidence in the article that suggests that individuals who get more REM sleep have less activity in areas of the brain that have been linked to fear. These findings might suggest that REM sleep may be capable of altering areas of the brain that communicate with one another in regard to fear. In other words, fear reactivity would be kept lower in people who have a higher proportion of REM sleep. This could have important clinical implications, especially regarding Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Park’s article on REM sleep and fear networks may represent an important component in better understanding the relationship between REM and PTSD. In the future, it might be possible to examine how much REM sleep a person gets and from that be able to gauge how resilient that individual will be in the face of trauma. It might also be possible to know how likely it is that individuals will develop PTSD after that trauma. This research might help us in the future to decide who is fit for high stress jobs based on sleep patterns. The article also poses several interesting questions. One interesting question is whether there is such thing as a REM “sweet spot” and if too little or too much REM sleep might both actually raise a person’s risk of PTSD. Too much REM might very well be a plausible issue given that there is a link between PTSD and intense nightmares that occur during REM sleep. Another question that comes to mind is causality. Although it seems simple to just be able to state that low amounts of REM sleep could cause PTSD, it’s also just as likely that having PTSD symptoms, such as reoccurring nightmares, could result in less sleep to begin with. We then find ourselves with the classic question of what came first, the chicken or the egg. Either way, this research is a prime example of how important it is to maintain a healthy sleep schedule.

Park, M. Y. (2017, October 23). Scared? Your Sleep Quality Could Be to Blame. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/60742-sleep-quality-fear-ptsd.html

Are Psychedelics a Possible Medical Treatment for Depression?

Kevin Lyskawa

In an article published by Tim Martin in The New Statesman titled, “The New Science of Psychedelics,” Martin embarks on current and past research that could hold promise for the medical use of psychedelics as a treatment for depression or anxiety. Within this article, Martin references work from many famous psychedelic researchers such as Robin Carhart-Harris, Bill Richards and more. With strong scientific evidence supporting Martin’s claims, he has revolutionized this schedule one drug to more than its common misconceptions, but rather a potential medical treatment for depression.

I want to first establish the background of psychedelics in society and in the scientific world prior to illustrating the scientific evidence that has emerged in recent years. Psychedelics were first discovered by Swiss scientist, Albert Hoffman, who at the time was studying the effects of lysergic acid diethlamide-25, commonly known as LSD, to cure raspatory issues and headaches. The story goes that while Hoffman’s results provided little to no evidence supporting his cause, he came into contact with the drug via fingertips during synthetization. Soon after, Hoffman stated in his journal that he began to experience the world in a different dimension, one filled with vibrant colors that seemed to differ than the normal visual spectrum. He left his laboratory to his home traveling on bike which gave rise to April 23, 1943 officially becoming known as “Bicycle Day,” becoming one of the first individuals recorded to experience a psychedelic trip.

Since Hoffman’s discovery, many researchers became fascinated with this new class of drugs. Research continued making immense headway into the possible benefits for treatment before president Nixon abolished psychedelic research by withholding government funding towards research during Nixon’s “War on Drugs” in the 60’s. The age of the drug loving “hippies” soon came to an end and research was halted for many years until a well-known scientist, Bill Richards, resumed his previous work in the late 90’s.

In a famous experiment performed by Richards, he wanted to see if psychedelics could have an effect on an individual’s outlook on life while suffering a terminally ill disease. Therefore, Richards conducted an experiment with 51 cancer patients who were suffering from chronic depression or anxiety and were given varying dosages of psilocybin, the psychoactive component in psychedelics. The patient’s feelings and attitudes on life after ingesting the drug were recorded and it was found that 80 percent of patients experienced a more positive outlook on life. It should also be known that these effects remained for over six months after experiencing the effects from the drug. That being said, Richard’s study indicates that psychedelics could serve as a one-time treatment for individuals with depression or anxiety.

Richard’s acknowledged that the shift in drug culture after the 60’s might make many reluctant to believe the benefits of such as drug. It should be known, however, that Richard’s will continue his research to hopefully one day convince the public that this is in fact a legitimate treatment, or should at the very least, be considered an alternative approach to treating depression. In my opinion, although the drug culture has taken its toll on many individuals and families who have suffered addiction problems in the past, psychedelics should be sought upon under regulation by practitioners a viable form of treatment. It will be interesting to follow the trajectory of psychedelic research because if sufficient evidence can prove the benefits, society must look past its previous history and come to terms with what could be a significant medical breakthrough.

Literary Cited

Martin, T. (2018, September 7). The new science of psychedelics. New Statesman; London, 147(5435), 32–35.

Richards, W. A. (2017). Psychedelic Psychotherapy: Insights From 25 Years of Research. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(4), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167816670996

The “Nightcap” Misconception

Georgia Beckmann

Alcohol is generally known to be a depressant (or numbing) substance, and “nightcaps” have been used for generations to help ease people to sleep. However, many research studies contradict this common belief and have found that in actuality, alcohol consumption disrupts sleep cycles and patterns, especially among habitual/binge drinkers and alcoholics.

A Patrick, Griffin, Huntley, and Maggs (2016) study found that college students reported worsened sleep quality and quantity following a night of binge drinking (defined as four or more drinks consumed by women and five or more drinks consumed by men in a single night). While this disrupted sleep could have been impacted by factors other than the consumption of alcohol, like the fact that these students may have stayed out late socializing, there are other studies to support the assertion that alcohol directly alters sleep patterns and is not simply a correlational observation.

A study by Roehrs and Roth (2001) uncovered a possible explanation for the “nightcap” misconception. According to their study, alcohol consumption in non-alcoholics improved sleep to an extent. Non-alcoholics that consumed lower levels of alcohol (meaning less than four or five drinks per night) experienced longer and higher quality sleep, but when they consumed larger amounts of alcohol (i.e. binge drinking), their sleep was worsened during the second half of the night. Roehrs and Roth (2001) also observed the impact of alcohol on the sleep of alcoholics, which process alcohol differently than non-alcoholics. As alcohol consumption becomes more habitual and consumers develop physical dependencies on the substance, the disruption of sleep becomes more chronic and persistent, and sleep disorders like apnea can develop. Apnea prevents sufferers from attaining restful sleep, or even much sleep at all, due to their inability to take in oxygen when unconscious. Similar to the trend in heavy drinkers and alcoholics, Ogeil et al. (2019) found that persistent heavy use of alcohol over time was correlated with poorer sleep quality among adolescents.

Based on these studies, and experiments performed by Chan, Trinder, Colrain, and Nicholas (2015), alcohol was determined to have an arousal effect on sleep waves and patterns, which competes with and inhibits delta activity which occurs during deep non-REM sleep (Carlson, 2013). The Chan et al. (2015) study found that alcohol increased frontal alpha activity, which competed with the delta activity to impede restful sleep. Though it is not clear exactly why alcohol reacts to disrupt sleep waves in this way, the arousing results are evidence that alcohol consumption, particularly in larger quantities, hinder sleep.

Additionally, the Chan et al. (2015) study provide a possible explanation for the sleep trends in adolescent drinkers and alcoholics because it demonstrated that alcohol actively prevents non-REM deep sleep, which results in less restful sleep. It is important that heavy nighttime drinking, which occur frequently on college campuses, is discouraged on the basis that habitual heavy drinking before bed can severely impede getting a restful night’s sleep due to the prevention of delta activity. Many studies have shown the negative impacts of sleep deprivation over time in general, and given the disruption alcohol consumption has on deep, restful non- REM sleep it is important to avoid large amounts of alcohol before bed as an essential aspect of healthy sleep hygiene.

References

Carlson, N. (2013). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience, ninth edition. New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Chan, J. K., Trinder, J. , Colrain, I. M. and Nicholas, C. L. (2015), The acute effects of alcohol on sleep electroencephalogram power spectra in late Adolescence. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 39, 291-299. doi:10.1111/acer.12621

Ogeil, R. P., Cheetham, A., Mooney, A., Allen, N. B., Schwartz, O., Byrne, M. L., . . . Lubman, D. I. (2019). Early adolescent drinking and cannabis use predicts later sleep-quality problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(3), 266-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/adb0000453

Patrick, M. E., Griffin, J., Huntley, E. D., & Maggs, J. L. (2018) Energy drinks and binge drinking predict college students’ sleep quantity, quality, and tiredness, behavioral sleep medicine, Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 16(1), 92-105, DOI: 10.1080/15402002.2016.1173554

Roehrs, T. & Roth, T. (2001). Sleep, sleepiness, sleep disorders and alcohol use and abuse. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 5(4), 287-297. https://doi.org/10.1053/smrv.2001.0162