Sample Five-Year Budget for Proposed Charter School in CT

A few weeks ago, Jacquline Rabe Thomas reported that five private operators had submitted applications to CT State Board of Education (SBOE) and CT Department of Education (CSDE) to create and operate new charter schools in Connecticut. This year, the applications for new charters would directly impact two suburban/rural towns, Danbury and Winchester, and two cities, Hartford and Norwalk. These applications can be viewed as a sales pitch by private education entrepreneurs attempting to get State government to shift public dollars to their charter school ventures.

Unlike previous years, there are some changes to how new charter schools get approved. Rabe Thomas noted that a recent change in the law required that the SBOE and CSDE call for applications for new charter schools on a yearly basis. However, there is no requirement to actually create any new charter schools. Also, the State Board of Education only recommends the creation of new charter schools through a “certificate”. Then the State Legislature has the final say on creation and funding of new schools. At least one reason for these changes came as a result of charter school entrepreneurs advertising for new charter schools that had not even been funded by the legislature, which placed legislators against parents that were promised a new school that did not yet exist.

In any event, it will be interesting to see what the SBOE and CSDE do given what we are learning about charter school issues and problems. For example, the NAACP has called for a national moratorium on charter schools because of excessive disciplinary practices, mixed records of achievement, siphoning resources away from traditional public schools into private ventures, and continuing segregation by race and ability. You can learn more about that charter school moratorium here.

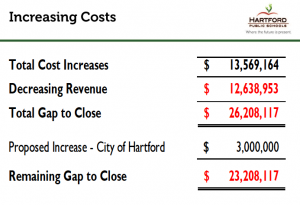

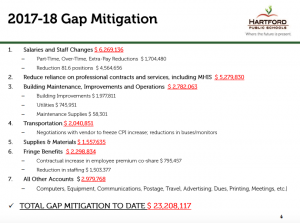

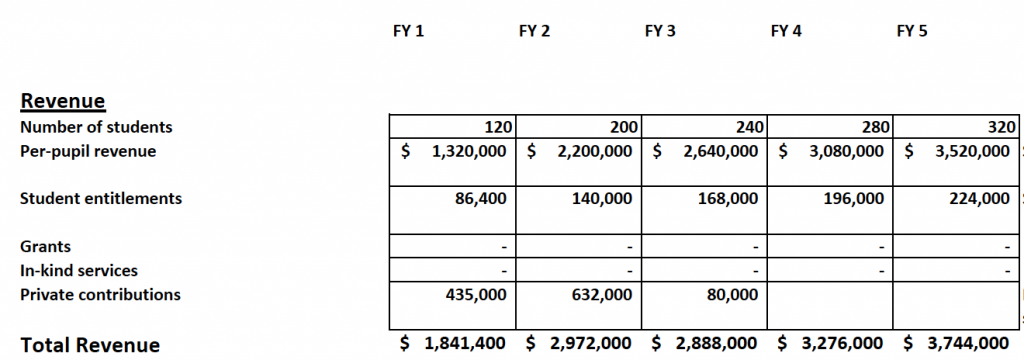

Reviewing these applications could be a daunting task given the amount of information presented in the five new charter school applications, which are several hundred pages in length. In addition to reviewing these long applications, there is also a context of financial strain. There is no State budget (as of 10/3/2017) and there is lack of consensus about the method of funding for public education and charter schools. Below you can take a look at the new charter school applications and find out what these entrepreneurs are trying to sell to the public this year.

Source: Connecticut State Department of Education.

Community First Charter School – Hartford

Danbury Collegiate Charter School

Danbury Prospect Charter School

Norwalk Charter School for Excellence

Winchester Academy Charter School

Winchester Academy Charter School (appendices)