In 1969, Trinity College enrolled its first coeducated class, accepting the first women to study at the previously all-male institution. In 1990, Professor Noreen Channels conducted a survey with the female graduates of the first twenty years of coeducation at Trinity. As Weiss Malkiel (2016) puts it, coeducation was not a triumph of feminism, women still make gendered choices in education, and issues of sexual harassment and assault are no more under control today than they were in the first years of coeducation. Looking at the answers Trinity graduates gave to the survey questions, one can determine whether this statement is true, whether coeducation was a success in the history of the college, whether the discrimination experienced by the first women who coeducated the institution improved over the years. Thus, this paper seeks to answer the following questions: Did the percentage of Trinity women who describe experiencing classroom discrimination or sexual assault against them or others increase or decrease as more women attended the college from 1969 to 1990? Are their accounts similar or different over time?

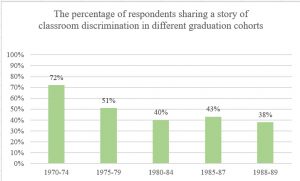

Through a detailed analysis of the survey responses, I will show that while the percentage of women describing classroom discrimination steadily declined – from three-quarters of the respondents of early 1970s graduates to roughly a third by the end of the 1980s –, the percentage of women experiencing sexual assault against them or others remained the same over the years. In terms of classroom discrimination, the types of experiences shared in the women’s accounts also show a gradual improvement – even with some issues, such as the lack of female faculty members remaining the same – from an overall feeling of not being treated as an equal to only experiencing discrimination or sexism from certain professors, and on a social level, rather than educational. On the other hand, the stories shared about sexual harassment and assault remain similar over the years: it seems like women’s concern for their safety, the general dismissal of assaults, and rapes or rape attempts remained an unchanged part of Trinity women’s college experience in the first twenty years of coeducation.

By 1955, 75 percent of colleges in the United States were coeducated, but many colleges – including such prestigious institutions as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale – remained all-male institutions until the end of the 1960s, while many women’s colleges existed as well. At the end of the 1960s, the second wave of the women’s movement became more active and visible, and the cultural changes led to single-sex institutions seeming old-fashioned. Thus, administrators at single-sex colleges began to worry that they would lose students to coeducated institutions, and many – Yale, Princeton, Amherst, Dartmouth, and so on – decided to become coeducational. The news that other institutions already decided to admit women or were considering doing so made Trinity College decide adopt coeducation as well (Miller-Bernal & Poulson, 2004). The reason why I believe it is important to examine the effects of this decision is because it not only profoundly shaped the life of the college itself, but because it had a lasting impact on the women’s lives who coeducated the institution. Also, it is especially important to analyze the experiences of these women with classroom discrimination and sexual assault because 92 percent of female Trinity students in 2010 expressed that issues of sexual assault, and being considered equal to men inside and outside the classroom are important issues to them (Hughes, 2010).

As mentioned above, to answer the research question, this essay focuses on Professor Channels’s “Survey of the Trinity College Alumnae”, conducted in the fall of 1990. This survey was mailed to approximately 3000 women who attended Trinity College from the start of coeducation, between 1969 and 1990, and was returned by 990 women. From Professor Channels’s report on the survey, it is known how many women returned the survey from different graduation cohorts (meaning whether they graduated between 1970 and 1974, or 1988 and 1989, for example). To see what percentage of these women shared an anecdote of classroom discrimination or sexual assault – the respondents could choose whether they want to share a story about being a woman at Trinity or not –, I simply counted the number of stories that Professor Channels categorized in the sections “Education, Classroom, and Faculty” and “Sexual Harassment and Abuse and Safety and Security Concerns”, and compared it to the number of women who answered the survey.

It is important to note that the experiences of women who responded to the survey are not necessarily representative of the experiences of the total female population attending the college. The women who answered most likely felt it is important to examine the question of women’s experiences after coeducation in a previously all-male college. However, it cannot be assumed that those women who did not answer the survey questions, or answered but did not share an anecdote, did not experience similar things, but also cannot be assumed they did. I do believe it is important to examine the answers of those women who thought it important to share their accounts, because we can get a rough picture of what it was like to attend Trinity College as a woman after coeducation.

To answer my question, I also had to determine the overall number of women attending the college in the years the survey respondents graduated. To do so, I looked at Trinity’s admission statistics that show the number of enrolled women in different years, and the US Department of Education’s NCES longitudinal data on post-secondary institutions that shows the total number of enrolled women on campus in certain years after 1980. This data tells us that in the beginning, when only the first-year class was coeducated, women on campus formed only a small minority in the overall student body, even with possible transfer students among the upperclassmen. According to the admissions statistics, 106 women were enrolled in 1969 to the class of 1973, and this number was growing over the years, resulting in a campus where half of the student body was female by the end of the 1970s: the NCES longitudinal study tells us that in 1980, 853 women attended Trinity, forming 47 percent of its student body.

Classroom discrimination

Among those survey respondents who graduated between 1970 and 1974, 72 percent shared a story about classroom discrimination. This number is 51 percent among those who graduated between 1975 and 1979, 40 percent among the graduates of the years between 1980 and 1984, basically the same, 43 percent among those from between 1985 and 1987, while it is only 38 percent among the graduates of 1988 and 1989:

This data tells us that as more women attended Trinity, the experiences of classroom discrimination decreased in number. Reading the stories these women share, there are themes that come up among all the cohorts: the encounter with sexist or misogynistic professors and male students; the experience with patronizing professors; the lack of female faculty members; the lack of attention to women’s issues; the lack of women from the curriculum; the lack of support for women and the lack of advising for them, especially in certain majors.

Even though many of the stories shared by women from the later years are similar to those from the earlier years, at a closer look these anecdotes show the gradual improvement in classroom discrimination, and Trinity’s development into a truly coeducated college in academic terms. The best indicator of this change is that those women who graduated in the early years of coeducation shared a feeling of Trinity still being an entirely male institution, while many of the graduates of the 1980s shared stories of support and feeling equal within the classroom – even if outside of it, in the social sphere, they still experienced discrimination. I believe that the alumna who graduated between 1970 and 1974 summarized the changes perfectly:

“Upon entering Trinity in 1969, I discovered that coeducation was a myth. At that time, Trinity was still a men’s institution, with some women in attendance. While a number of male students displayed extremely negative attitudes to the female presence, the faculty response was even more disappointing. The professor who announced that no woman in his course would ever receive a grade higher than a “C” stands out in my mind. In visiting the campus over the last 20 years, I have observed that the situation has improved with the increased numbers of women on campus. Trinity’s evolution into a co-ed college appears to be a success – but one should not believe that it happened overnight. Academically, Trinity has stood me in a very good stead for both my graduate studies and my career. I sincerely hope those standards have not fallen.”

As this quote tells us, the first women who arrived at Trinity did not feel welcome by male upperclassmen and professors, since many of them expressed negative attitudes towards change. Even though this general feeling of Trinity still being a men’s institution has changed over time, the encounter with one or several sexist or misogynistic professors remained an experience that many female Trinity graduates shared. Those graduating between 1970 and 1974 shared stories such as “being counseled about classes by a senior professor who said he didn’t believe in educating girls”, and “the chairman of the department made it quite clear that he did not want women in his department”. One of the strongest descriptions of such open discrimination in the classroom is the following, shared by an alumna who graduated between 1975 and 1979:

“In labs, he would ridicule all the women and refuse to answer any of their questions. ‘Oh, I don’t see any hands up in this row’, when I was waving it 2 feet from his face. On the other hand, he would coddle with the guys and practically do their experiments for them if they didn’t understand. He would cruise the lab room making sexist remarks and laughing and ignoring any requests from women. I dropped the course. (He gloated during a particular lab which required us each to use our own urine, and cackled when women’s labs would be ruined if it was the wrong time of the month for them – they were not allowed to use someone else’s if they had a problem.)”

Many of these women explain how they felt that racism and sexism were similar dynamics, such as in cases like the one described by an alumna: “One teacher told me that women and blacks don’t belong in college. The women and blacks all got C’s in that class – the only C I got at Trinity.” Among those who graduated in the later years, these experiences became much rarer, and if they encountered sexism on part of faculty members, they usually wrote that it was only one particular professor in one particular department, and they believed that it was not a characteristic of the entire school environment by then:

“The only negative memory I have regards one episode of discrimination. I was told by the science professor that the only reason I was a lab assistant was in case a woman spilled a chemical on herself and needed to be showered down. To my surprise the professor also told me that wiping up spills would be a useful skill for my further role as a housewife. Fortunately, I knew that he voiced many strong opinions, and I did not place much importance in his opinion – beyond disbelief that such attitudes existed. I don’t think this experience was at all characteristic of Trinity.” (Alumna who graduated between 1980 and 1984.)

Thus, over time, overt sexism on the part of professors became something that women students experienced less often, while experiencing sexism on the part of male classmates in educational settings also seem to have disappeared by the 1980s – while, according to many survey respondents, it remained an important part of social life at Trinity. In the early years of coeducation, many upperclassmen resented the female presence – with many of them being accepting of course – but the situation improved significantly and, since this type of experience seems to be missing from the experiences of those who graduated in the 1980s, rapidly:

“There was a certain amount of vocal unwelcoming noise expressed mainly through the Tripod by upperclassmen who opposed coeducation at Trinity. Coming from a public high school it was sometimes hard for me to keep these negative comments in perspective. However, the majority of the students were accepting, and the situation continued to improve from year to year.” (Alumna, graduated in the years 1970-74.)

Thus, by the end of the 1970s, male students accepted women’s presence in the classroom, as a graduate from between 1980 and 1984 described “being taken just as seriously by men (students/faculty) educationally, but not fully socially.” Then, as I described, most professors did not demonstrate explicit sexism, but subtle forms of discrimination and patronizing attitudes are present in the stories of students from the later years as well, along with the seemingly unchanged assumption on the part of many male professors that women are only in college to find husbands or that they are only going to work until marrying, then becoming a housewife, and thus, there is no need for them to study anything hard or challenging:

“Although he did offer some advice, his overall tone was extremely patronizing. He remembered how when he began at Trinity there were no female students, and advised me not to worry about the class because someday (he felt in the future) I will be married and this will be unimportant. He advised me to take ‘nice’ courses in the future. He suggested a language course. That was my first and last science course at Trinity.” (Experience with the lab compartment of a science class, alumna graduated in the years 1985-87.)

Another issue that is present in many female graduates’ anecdotes is the lack of female faculty members, often combined with the opinion that the presence of female role models, especially in majors that are male-dominated, would be important and inspiring to young women attending the college. While many of the women expressed the need for more female faculty members, many also shared an encounter with an inspiring woman professor, which shows why it would be important to have more women in the faculty as the college got coeducated:

“I was fortunate enough to meet a female faculty member, who played a crucial role during my last year at Trinity, and I am now pursuing a graduate degree. Had I not had the positive experiences and encouragement during my senior year I may not have chosen to pursue graduate work.” (Alumna who graduated between 1985 and 1987.)

What is especially important about this opinion is that this situation does not seem to really improve over the years, it is still present in the accounts of women who graduated in the end of the 1980s:

“Although this isn’t a specific memory of my experience at Trinity, the lack of positive female role models in the ‘science and math’ departments, clearly remains as a strong, disconcerting memory of my college experience.” (Alumna who graduated between 1985 and 1987.)

Along with the lack of female faculty members, many survey respondents remembered that in general, there was a lack of attention to women’s issues, that women were missing from the curriculum, and that women lacked support and advising, especially in certain majors, most likely math and science. This issue does not seem to improve over the years, as women who graduated in the 1980s still shared experiences such as being ridiculed for expressing feminist views – as the account of a graduate from between 1980 and 1984 tells us:

“Oftentimes we were discouraged – as in the case of being called a “lesbo” or having new ways of doing history disparaged. There were many sacred cows, not to be questioned, but fraternities were the most sacred of all. Questioning the fraternities meant you were ‘militant’ or weird. Certainly you’d be isolated and, of course, you were socially ugly. These messages can be conveyed subtly as well as explicitly – and I’d say it was more the build-up of subtle messages than incidence that convinced me I was a feminist – and very proud of it.”

The term used by this alumna – “socially ugly” – highlights how, even though discrimination and sexism on the part of most professors and male students was not an issue by the end of the first twenty years of coeducation, social discrimination was still often experienced by female Trinity students, while some issues – like the lack of female faculty members –remained relatively unresolved. Overall, I would argue that we can agree with the alumna who graduated at the end of the 1970s who said that by the time she enrolled in the college, “coeducation was no longer a big deal”. In academic terms, Trinity College’s coeducation seems to have been successfully implemented by the time of Professor Channels’s survey. Looking at the responses categorized in the survey’s sexual harassment and assault section gives us a different picture that shows that determining whether coeducation was a success is a more complicated task.

Sexual harassment and assault

The percentage of women among the survey respondents who shared a story of sexual harassment or assault that happened to them or to others, even though quite low, remained technically unchanged over the years: among the graduates between 1970 and 1974 this number is 13,5 percent, between 1975 and 1979 it is 14 percent, between 1980 and 1984 it is slightly higher, 23 percent, between 1985 and 1987 it is 18 percent, and it is 13 percent among the graduates of 1988 and 1989:

Even though these numbers are low, and many women shared not their own experiences but that of a friend, a roommate, or a story that they simply heard of, the fact that these experiences were so important to them that they share it after several years show that these experiences cannot be dismissed. Also, as it is known, survivors of sexual assault often do not share their stories.

Women who graduated in the early 1970s and those in the late 1980s all shared similar stories: concern for safety, especially when walking home at night; verbal assault and degrading comments; being harassed in fraternities or by professors; rapes and rape attempts; and most importantly, the general dismissal of these cases, are experiences that remained a part of female Trinity students’ campus life over the years. One story that stands out is the gang rape incident that happened in one of the fraternities: this story appears in almost every account of women who graduated between 1980 and 1984, and even appears in the stories of later graduates. The fact that so many women felt it is important to share this story probably explains the higher percentage of women sharing a story of sexual assault in this cohort. Most of the accounts of these women describe how the administration did not deal with the incident in a way they were supposed to, and how awful they felt when they learned that many of the male students actually supported the members of this fraternity:

“The event I remember in particular is a gang rape that occurred at Crow one year to a woman non-student. I remember feeling disgusted, angry, helpless as well as humiliation for my feelings about it. The school put Crow on probation – no parties or something – the event was extremely controversial. Most of the men I know supported the Crow brothers involved and many of the women I knew were silent (as was I), or passively supportive. I could not understand why nothing more was done and why the frat system couldn’t be abolished completely. It does nothing for the status of women there – and there’s no need for it at such a small school. Really.”

Although no other event was highlighted in the graduates’ accounts as many times as this gang rape, many other women experienced rape or rape attempts during their years at Trinity. In some cases, this was done by strange men who entered the dorms and people’s rooms while they were sleeping. Oftentimes, it was done by fellow male students: male students attempted rape in dorms’ showers, in the hallway, and so on, but date rape is also an issue that often comes up in the stories, with the account of an alumna who graduated between 1985 and 1987 being one of the most disturbing:

“I was far from being in a compromising position when he suddenly jumped on top of me with a hand holding my mouth when 4 of his fraternity brothers came in, ripped off only my clothes that were necessary for their purposes and all proceeded to rape me, my ‘date’ still holding me down. Thoughtfully they all wore condoms so I had no physical results of this act but I don’t think I have to go into the emotional results. Looking back I wish I had reported them and ‘destroyed’ them the way they had me. (…) My friends were sorry for me but we all came from nice towns and nice schools and this didn’t happen to ‘nice girls’. Maybe that’s one reason I didn’t report it. I also came to Trinity a year after the ‘Crow Incident’.”

As it can be seen, this alumna not only referred back to the gang rape in Crow in the previous year, but she also felt a sense of guilt after she was raped, and she also gived an explanation of why she did not report the incident. Those who reported such cases, however, often faced an administration that tended to dismiss the cases: women were often pressured not to press charges, often because they were told that it would hurt the college’s reputation. Also, as the account of an 1985-87 graduate whose roommate was raped tells us, if the perpetrator’s family was wealthy, there was usually nothing done to them:

“The man that had raped her was a senior at Trinity. His family was very wealthy, he was a fraternity brother (not that those are related). Because it was spring semester and he was about to graduate she was advised against pressing charges. It would have been her word against his and he had more money. There was never a security alert about the incident and not one thing was done to the man. He was graduated and went on his merry way while my roommate was made to feel that she’d done something wrong and she was a bad person because she’d gone to his room on their way back from the Summit. That’s rotten. Trinity and everyone else failed in that situation and my roommate transferred.”

Of course, not all women who shared a story of sexual harassment and assault told an experience of rape or rape attempt. An issue that comes up more often is the women’s concern for their safety, especially when walking home at night. Many of these accounts link this to the fact that Trinity is located in the inner-city – some even blaming administration for not preparing the students for inner-city life while most of them are used to suburbia. However, even though some women were actually attacked or harassed by locals, a just as often talked about issue is being harassed in fraternities. Women shared the experience of “feeling like a piece of meat in a frat party”, where an alumna from the years 1980-84 also experienced “hearing a girlfriend pleading to be let out of a room in a frat house and realizing that not one of the guy’s ‘brothers’ would step in to tell him to let her out”. Especially after the “Crow incident”, as the gang rape is often referred to in the women’s accounts, the fraternity scene felt even less safe for many of them:

“It all represented to me the worst of the whole fraternity scene. It opened my eyes and politicized me. The whole fraternity scene no longer felt safe to me. (…) The whole incident was quickly hushed up. I blame the administration for that. (…)” (Alumna, graduated in the years 1980-84.)

Although a less frequent experience, especially in the accounts of the women who graduated in the 1980s, some of the alumnae shared anecdotes of being harassed by a professor. Oftentimes, the refused professor gave the female student a worse grade, and just as in the case of rape committed or attempted by male students, this harassment was also dismissed by the administration:

“A member of the faculty made sexual advances to me. Upon reporting the incident to the [administration], I was asked if I had ‘led him on’ – this an overweight, over seventy professor. His chairman insisted I had made the whole thing up – despite the fact that as I learned later, the same professor had been reported to the Dean six times in the past. What did I think about being a woman at Trinity. Ge, it was just swell.” (Alumna who graduated between 1975 and 1979.)

A last issue that is often shared in the women’s accounts over time is that of experiencing verbal assault, receiving degrading comments, such as being called out for wearing a short skirt in a classroom, or being called a “feminist bitch” when expressing concern about harassment. In terms of such comments, what seems to be an unchanged experience of Trinity alumnae over time is that of being rated based on their appearance upon arrival at the college by upperclassmen:

“I remember vividly being excited about attending Trinity because I was in the first class of women fresh’men’ and though that a great challenge. Especially being one of 100 women amidst 1200 men. Upon arriving I was hurt by the men’s reaction. They seemed dismayed that we had arrived and only had interest in meeting the women whose pictures were most attractive in what was then called the ‘freshman pig book’.” (Alumna from the first coeducated class.)

As the above described percentages already told us, the issue of sexual harassment and assault remained relatively unchanged in the first twenty years of coeducation. The different experiences women shared in their anecdotes show that graduates at the end of the 1980s faced very similar situations as those in the early 1970s. Even though an “awareness day” was introduced after the often-cited gang rape incident, it can be seen that while Trinity appears to have successfully achieved coeducation in terms of equality in the classroom, female students’ stories about sexual assault do not show such improvement.

Conclusion

In his analysis of Professor Channels’s survey, Peter J. Knapp (2000) argues that “as the survey reveals, coeducation has touched the lives of alumnae in varying ways, in the process working as well to alter the life of the institution” (p. 382), and that even though coeducation was a difficult experience for some, it was also an extraordinary opportunity. After reviewing the stories that female Trinity graduates shared, I would conclude that coeducation has definitely altered the life of the institution, as by the end of the 1980s, classroom discrimination that was such a common experience of the first women who attended the college, was only experienced by some. However, the numbers and issues of sexual harassment and assault remained technically unchanged over the years, suggesting that the social integration of men and women was not entirely successful in the first twenty years of coeducation. Whether this situation has improved in the almost thirty years since Channels’s survey is questionable, but it would be interesting to explore in further research. Comparing the experiences of Trinity graduates to those of other nearby colleges, or to those of the alumnae of previously all-women colleges would be fascinating and important to explore as well.

Works cited:

Primary sources:

Channels, Noreen L. (1990): Survey of the Trinity College Alumnae. (Available at the Watkinson Library)

US Department of Education’s NCES longitudinal data on post-secondary institutions (Database available at: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data)

Trinity College Admission Statistics of 1969-1998 (Available at the Watkinson Library and Google Spreadsheet)

Bibliography:

Hughes, James (2010): 2010 Survey of Female Students at Trinity College. Available at: https://share.trincoll.edu/SiteDirectory/irp/sextant/Lists/Posts/Post.aspx?ID=2 (Last visited: March 30, 2018)

Knapp, Peter J. (2000): Coeducation, Long Range Planning, and the Advent of Information Technology. In: Trinity College in the Twentieth Century. Hartford, CT: Trinity College, pp. 365-466.

Miller-Bernal, Leslie & Poulson, Susan L. (2004): Going Coed: Women’s Experiences in Formerly Men’s Colleges and Universities, 1950-2000. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Weiss Malkiel, Nancy (2016): Coeducation at university was – and is – no triumph of feminism. aeon, November 8, 2016. https://aeon.co/ideas/coeducation-at-university-was-and-is-no-triumph-of-feminism. (Last visited: March 30, 2018)