The United States is known to be the land of opportunity and upholds the ideals of the “American Dream.” This “dream” includes providing equal opportunities for residents of the nation to journey into a life of success and prosperity. The American Dream is a motivating force for foreigners to immigrate to the United States for the chance to reap social, political, and economic benefits that their country of origin cannot provide. While some individuals patiently wait to immigrate to the United States legally, others desperately immigrate illegally for survival, and along come their children, unwillingly. Within the immigrant population lies a very vulnerable sector of individuals known as Dreamers. This term comes from the legislative Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (Dream) Act, introduced but failed to pass Congress in 2001, that focuses on “immigrant integration [and] addressing the problem of how young [students] who know no other country and identify as American best participate and contribute to the American society” (Zatz and Rodriguez, 2015). The challenge holding legislatures from granting these individuals citizenship is the polarized view of “protecting children from the consequences for actions over which the child had no control, while others frame the Act as a reward for illegal activity that would create an incentive for minor children to enter into the United States illegally” (Georgetown Law Library). After 11 years of revisions and rejection of the Dream Act, in 2012, President Obama made an executive order to implement the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to temporarily protect Dreamers. Despite political disagreement, more Americans have jumped on board to support the legalization of long-term immigrant students. As a result of this change, I want to pose the question: How have political leaders shaped opinions about long-term immigrant students from the introduction of the Dream Act in 2001 to the current debate over DACA today?

To date, the United States continues to face challenges of protecting its sovereignty as it faces increasing amounts of illegal immigration. Although the nation battles with strengthening border control between immigrants and Americans, immigrants travel to the United States to contribute to the United States’ society as an attempt to reap the benefits of the American Dream. Lacking legal documentation to gain respect for their societal contributions, many political leaders have been hesitant to honor the benefits and are quick to point out the consequences that immigrants have contributed to the society. Since the introduction of the Dream Act in 2001 and the implementation of the DACA program, the opinions behind immigrant students have shifted but continue to face pushback from those who believe that immigrants do not deserve citizenship for any reason. Since the 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump, debates over protecting DACA have been heightened causing many Dreamers to face a torturous fear of the program ending any day. While many extremists continue to fight against legalizing Dreamers, the upward shift in opinions has been a result in the reality of how America has tremendously benefitted, quantitatively, from Dreamers through their talents, values, and contributions to the economy.

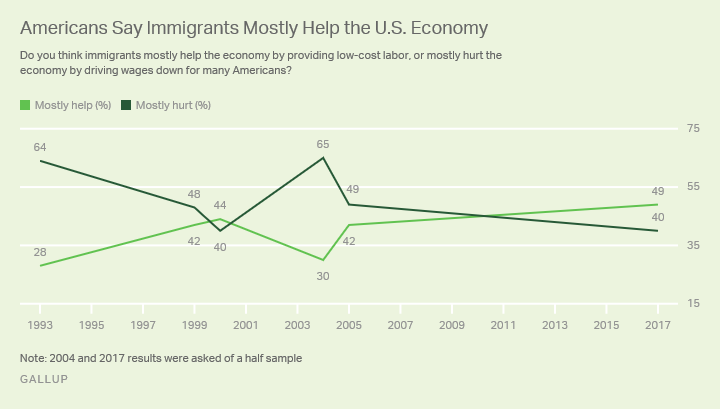

In terms of immigration reform policies, measures that impact undocumented immigrant rights, such as granting citizenship, is traditionally supported by Democratic legislatures. As for the Republican party, there is generally more pushback for implementing immigrant rights. This conflict was especially the case dating back to the Republican party’s anti-immigration movement in the mid 1990s that included the introduction of Proposition 187 by Republican governor Pete Wilson (Wroe, 2008). This policy denied public services to undocumented residents of California and required persons to report “suspected” illegal immigrants to the authorities. In effort to maintain the support of his voters, Wilson used the presence of illegal immigrants as a scapegoat for the long and deep recession of the time period. Wilson stirred feelings of resentment within the public towards illegal immigrants by speaking “out against illegal immigration, arguing that undocumented persons took jobs, burdened schools and hospitals, and avoided taxes” (Wroe 2008). At the time, nearly two-thirds of U.S. citizens thought more harm than good for the economy and the choice of rhetoric used by Wilson was one contributing factor (Swift 2017).

The United States has always taken great pride in the value of citizenship. Politics of race, gender, ethnicity, and social class are determining factors for the decision making of the country. Previous to the introduction of the Dream Act in 2001, President Ronald Reagan, Republican, made first attempts to confront social, economic, and political issues regarding US immigrants through the Immigrant Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1986. This act was an attempt to control the legalization of immigrants and regulate employers from hiring undocumented individuals. In his announcement speech, President Ronald Reagan’s expressed the motive behind passing IRCA:

“Future generations of Americans will be thankful for our efforts to humanely regain control of our borders and thereby preserve the value of one of the most sacred possessions of our people: American citizenship” (Wooley, Peters 2018).

President Reagan presented the pride in having and protecting a status of citizenship in the United States to the values of the nation. Reagan used his political power to influence Americans’ opinions of who deserves rights, access, and possession to the land. In 1993, 64% of Americans believed immigrants mostly hurt the U.S. Economy (Swift, 2017). Evidently, between the years of President Reagan and into the 1993 prelude presidential term of President Bill Clinton, the opinions about immigrants in the United States were very unsupportive of legalizing those who were undocumented. Although IRCA resolved immediate issues by controlling the legalization of immigrants and regulating employers from hiring undocumented individuals, the reform failed (Zatz and Rodriguez, 2015). The number of undocumented and “unauthorized immigrants living in the country soared, from an estimated 5 million in 1986 to 11.1 million by 2013 (Plumer, 2013).

As a result of 9/11 attack on the United States, enforced security of immigrants entering and undocumented individuals living in the country accelerated. It was the first time in 14 years that the “traditional unauthorized inflow [had] been flat or falling (Rosenblum, 2015). A huge influence for this reaction was the implementation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) which was the larger umbrella over other agencies: Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP), and US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) (Zatz and Rodriguez 2015). These agencies lead to a large number of raids in under-the-table workforces and immigrant homes across the country. Likewise, the measures of border security led to increased demands for exceptions over Dreamers, “the group of immigrants who may be well-assimilated, have good and useful jobs, or exhibit some other attributes that resonate with the values and moralities of nationals” (Nicholls, 2013). Action towards the issue of undocumented students brought to the United States unwillingly and unjustly facing consequences for actions they had no control over was in high demand.

In 2001, political leaders, Democrat Dick Durbin and Republican Orin Hatch, served as the voice for the Dreamers by introducing the Dream Act. This was an attempt to demand for action to be taken to protect the vulnerable sector of students in America. Specifically, the act proposed to create a path to citizenship for students who came to the United States before the age of sixteen, who are still below the age of thirty-five, who have resided in the United States for at least five years, who completed high school (or equivalent schooling, like a GED), and who enroll in either an institution of higher learning or the military (Keyes, 2013). Although failed to pass both chambers of Congress, this act was the ignition of conversation across the country about who deserves rights to resources in America, such as access to higher education.

Since the promotion of Dreamers in 2001, many house representatives continue to be hesitant to support full citizenship for those who have come to the country illegally; however, there has been a shift in political and public support for the consideration of legalizing Dreamers. A huge motive for this change of opinions are the results of the relationship between the economy and protecting undocumented immigrants. Being an everyday contributor to the United States’ society, statistics show granting citizenship to undocumented workers would significantly improve the American economy. The U.S. economy has “never before confronted such significant shifts in its industrial, occupational, and geographical employment patterns nor has it experienced such growth and compositional changes” (Briggs, 1996). From an economic perspective, the United States will dramatically be impacted if it were to experience a decline in immigrant populations.

Without citizenship, Dreamers are unable to pursue higher education because of the inability to apply for financial services, such as federal financial aid and in-state tuition. With the “increasingly competitive global market and economy demands more access to education so that [Dreamers]” can enter various sectors of jobs then strengthening the workforce. The increased demands for immigration reforms has encouraged many political leaders who previously opposed protecting Dreamers to shift their rhetoric about immigrant rights. In addition, the presence of Latino policymakers contribute to the change in opinions as they serve as an informative tool within politics to educate their co-leaders on the circumstances of Dreamers in the U.S.. (Nienhusser, 2015). As a result, the percentage of Americans who believe immigrants mostly help the U.S. economy has steadily increased since 2001 (Swift, 2017).

In response to 11 years of Congress’s inability to pass the Dream Act, several legislators sent President Obama letters urging him to use executive action to stop the deportation of innocent immigrant students in the United States. In 2012, President Obama introduced the DACA policy as a way to respectfully acknowledge Dreamers as “Americans in their heart, in their minds, in every single way but one: on paper” (Keyes, 2013). This policy grants Dreamers two-year renewable prosecutorial discretion from deportation and authorization to work. This has since given privilege to Dreamers to pursue a higher education and legally work in areas serving higher wages. Since the implementation of DACA, “beneficiaries have been able to get better paying jobs and in general become more financially stable” (Ortega, Edwards, Wolgin, 2017). Furthermore, in return, this has led to more tax revenue and greater economic benefits for localities, states, and the nation as a whole. Despite evident progress in the economy through temporarily granting Dreamers equal opportunities, opposing attitudes towards Dreamers continue to be a disruption on serving the nation’s interest. Republican Lamar Smith of Texas, chairman of Judiciary Committee views the Dream Act as “an American nightmare” because it would displace american students from public colleges (Preston, 2011). Representative Steve Pearce, a New Mexico Republican slightly shifted away from the general consensus of the Republican party and believes “if there are jobs for those people, then fine, let’s give them legal status, let’s give them work, but not citizenship, because that’s going to take benefits away from my family” (Parker, 2013). It is evident that providing Dreamers the legality to work will benefit the economy; however, Wilson’s rhetoric and emphasis that illegal immigrants steal goods (i.e. access to higher education) and are a burden to the society in the mid 1990s continues to creep in the minds of Americans.

Today’s political climate over the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals protecting Dreamers has intensified since the election of Republican President Donald Trump. In the years of 2015 and 2016, Trump campaigned on a platform of increased security and regulation of undocumented immigrants already living in the U.S. The debate over illegal immigrants in the U.S. has intensified due to Trump’s emphasis of the negative embodiments that immigrants bring to the country, such as “Haitians all have AIDS and declaration of countries in Africa as ‘shithole countries’” (Kirby, 2018). His rhetoric for the demand of “immigrants who can contribute to our society, grow our economy, and assimilate into our great nation” reproduces the “nation-state standards that define whether a person is a “good” and “deserving” member through a racial lense (Kirby, 2018; Carrasco, Seif 2014). Regardless of the “87% of Americans who favor granting protections for DACA immigrants,” Trump’s administration threatens to curtail DACA (Auter, Lall, 2018). Since Trump’s election,“partisan views on immigration appear to reflect the rhetoric and actions of his administration – Republicans dissatisfaction with immigration has dropped 16 percent, while Democrats’ dissatisfaction has risen 16 points between 2017 and 2018” (Auter, Lall, 2018). Causing much frustration, worry, and eagerness, Trump has yet to disband the DACA program knowing “immigration is an economic phenomenon and that its regulation is an instrument of economic policy making” (Briggs, 1996). Other political leader have encouraged for decisions behind policy making exclude “divisive politics and recognize [the] shared interest in common-sense immigration reform/affirm [the] perspective of what reform and human rights looks like through [the nation’s] actions” (Carrasco, Seif 2014).

The United States, also known as the land of opportunity, has had a broken immigrations system for decades creating a situation were a significant population of undocumented students struggle to integrate into society. As a product of the political rhetoric and work of political leaders, the public opinion, state legislators, and federal courts are dramatically shifting as they consider the needs of Dreamers and allocating equal opportunities to reap benefits of the United States. Since the introduction of the Dream Act and the evolution of the DACA program, ”undocumented young people are redefining what constitutes good citizenship to include those of us who have limited access to education, work in the underground economy” (Carrasco, Seif, 2014). With the shift in political and public opinions of Dreamers, the undocumented students who grow up associating themselves with an American identity will no longer have to worry about not having the same opportunities as their native counterparts to fulfill their dreams.

References

Auter, Z. and Lall, J. (Jan. 23, 2018). Republicans’ Dissatisfaction With Immigration Down, Democrats’ Up, http://news.gallup.com/poll/226175.

Briggs, R. (1996). Immigration Policy: A Determinant of Economic Phenomena. Mass Immigration and the National Interest: Policy Directions for the New Century, 7-22.

Carrasco, T. and Seif, H. (2014). Disrupting the Dream: Undocumented Youth Reframe Citizenship and Deportability Through Anti-Deportation Activism, Macmillian Publishers Ltd, 279-299.

Georgetown Law Library (2018). A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States, Georgetown Law, http://guides.ll.georgetown.edu.

Kirby, J. (Jan 11, 2018). Trump Wants Fewer Immigrants From “Shithole Countries” and More From Places Like Norway, https://www.vox.com/2018/1/11/16880750/trump-immigrants-shithole-countries-norway

Nienhusser, H. (2015). Undocumented Immigrants and Higher Education Policy: The Policymaking Environment of New York State, The Review of Higher Education, 271-303.

Nicholls, W. (Sep. 2013). Introduction. The DREAMers: How The Undocumented Youth Movement Transformed the Immigrant Rights Debate, 1-16.

Ortega, F., Edwards, R., and Wolgin, P. (Sep. 18, 2017). The Economic Benefits of Passing the Dream Act, Center for American Progress, 1-14.

Parker, A. (July 25, 2013). Sign of Hope Seen InHouse For Immigration Overhaul. The New York Times, http://www.immigrationworksusa.org.

Plumer, B. (Jan. 30, 2013). “Congress Tried To Fix Immigration Back in 1986. Why Did It Fall? The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news.

Preston, J. (Feb 8, 2011). After A False Dawn, Anxiety For Illegal Immigrant Students, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/09/us/09immigration.html.

Rosenblum, Marc R (2015). “A New Era in US Immigration Enforcement: Implications for the Policy Debate.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 16, no. 2, 122–132., www.jstor.org/stable/43773702.

Swift, A. (June 29, 2017). More Americans Say Immigrants Help Rather Than Hurt Economy. http://news.gallup.com/poll/213152.

Woolley, J. and Gerhard, P. (2018). Ronald Reagan: Statement on Signing the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu.

Wroe, A. (2008). Introduction. The Republican Party and Immigration Politics, 1-10.

Zatz, Marjorie Sue, and Nancy Rodriguez (2015). Dreams and Nightmares: Immigration Policy, Youth, and Families. University of California Press, 10