When discussing sex education in the United States, there are a number of reasons as to why it is a controversial subject taught in schools. Differences in religion, questions of age appropriateness, and varying opinions in regards to whether co-ed or single sex education is more effective, all plague the integration of successful sex education programs into schools across the nation. Sexual boundaries in the 1950’s in the United States were very clearly defined: there was no pre-marital sex, and the path to marriage began with friendship, moved to courtship and “going steady”, and ended with a heterosexual marriage and children. These societal understandings influenced the types of sex education taught in schools beginning in the elementary years. Activities and lessons taught students that men were breadwinners, broadly meaning that men had the job that supported themselves and their families, were in charge of finances within the family, had their main responsibilities outside of the home. The same lessons taught students that women were homemakers: women were expected to keep a clean home for their husbands’, supported their husbands’, and gave birth and raised their children to grow up and accept these same gender roles. My research asks the following questions: how were male and female gender roles portrayed in U.S. sex education materials before the sexual revolution in the 1950’s, and during the sexual revolution of the 1960’s. Also, how do the gender roles presented in 1960’s materials differ from those presented in sex education materials today?

I argue that although one would expect sex education materials during the sexual revolution in the 60’s to have changed due to a society’s changing acceptance of appropriate gender roles, in reality, they looked very similar to, if not unchanged, from sex education materials in the 50’s. When looking at sex education from the 60’s to today, however, there are dramatic changes regarding redefining gender roles within society. More specifically, sex education curricula that are widely used throughout the nation, such as the SexEd Library 1 , and many others, include full lesson plans to discuss with students the current gender roles within society and how to confront situations where one feels uncomfortable in the role that they are placed in.

The 1950’s represent a time where people were expected to live their lives within the confines of acceptable social behavior, which embodied a moral, heterosexual way of life. The definition of sex education in the 1950’s and 1960’s remained the same according to H. Frederick Kilander’s book “Sex Education in the Schools.” It was defined as:

“[including] all educational measures which in any way may help young people prepare to meet the problems of life that have their center in the sex instinct and inevitably come in some form into the experience of every normal human being.” 2

Despite changing beliefs of what a “normal human being” experience was in the transition from the 1950’s to the 1960’s, this definition remained a standard for sex education courses. The 1950’s sex education materials depicted an image of stereotypical men and women in society, which pressured young students to adhere to these presupposed roles.

Source: YouTube 3

Source: YouTube 4

These two films are examples of lessons taught in sex education classrooms in the 50’s before the sexual revolution began. There are many obvious examples of stereotypically defining gender, and elementary and secondary school-aged students were absorbing these values and understandings. At this very vulnerable and influential time of life, students were understanding of the roles of men and women in society, and were expected by their teachers to mimic their actions. These same values and lessons taught within sex education courses can be found in “Sex Education in the Public Schools” by G.G. Wetherill. This book describes a sex education curriculum from the 1950’s in San Diego, California with an extremely strong emphasis on the differences between boys and girls both physically and in relationships, family lives, etc. 5 In a report on the book written by G.G. Wetherill himself, he mentions one lesson that is responsible for the discussion of “strengthening right attitudes toward sex and growing up, boy-girl relationships, and moral and spiritual values.” 6 In the same curriculum, Wetherill describes one of the ultimate goals of the lessons as being to “encourage good home teaching, interpret masculine and feminine roles in society…” 7 The focus on a traditional family life with a mother that is at home raising the children and keeping the household functional, and a father who is working throughout the day and making an income to support the family is emphasized in this program, and can be seen in Jeffery Moran’s “When Sex Goes to School.” Moran interprets Wetherill’s curriculum in the following way: “In short, family life education had become the remedy for almost all the problems that plagued individuals or communities at midcentury.” 8 To look at the way stereotypical gender roles were more specifically inserted into sex education materials in the 50’s, Esther Schulz and Sally Williams’ “Family Life and Sex Education: Curriculum and Instruction” includes a section called “The Physical Aspects of Necking and Petting” from a 1959 curriculum in New York. This lesson is directed towards a girl who is out on her first date with a young boy who she would like to “go steady” with. The entire story is extremely emotional and sensitive, with sentences such as “the emotions that this kind of kiss stirs are not simple and straight-forward and uncomplicated. This kiss evokes more than a simple exchange of pleasant thoughts.” 9 The very sensitive way of describing this big step in an adolescent’s life is stereotypical of all sex education lessons for girls in the 50’s. As the lesson continues, there is more discussion of what a girl learns from her parents about cheating: “in grade school you learned not to cheat, and you didn’t cheat, because your parents and the teacher said not to.” 10 Finally, the lesson strongly advises the girl not to have premarital sex because it ruins her reputation as a moral young woman and causes various other problems in her life:

“pregnancy outside of marriage is a mistake because it hurts you and the child, your family, and the man who is the father of the child. Only a very irresponsible or immature person can ignore these responsibilities.” 11

The end of the 1950’s came with drastic changes in the way women and men viewed themselves and their gender roles in society, however, sex education lessons and materials did not change to accommodate the nation’s changing perceptions.

As the 1960’s approached and the U.S. began to experience a change in the perception of sexuality and appropriate sexual behavior, older generations were shocked. Young women were presenting themselves as what society believed to be immoral by proudly exclaiming that they have had multiple sexual partners before marriage. Moran’s book showed the media portraying young women making statements such as, “we’ve discarded the idea that the loss of virginity is related to degeneracy.” 12 Kristin Luker’s “When Sex Goes to School” interpreted the 1960’s in the following way: “sex, gender, marriage, and authority were all enmeshed in the sixties, and the sexual revolution represented them all.” 13 As changes like this continued to occur and the media played an integral role in presenting women as increasingly powerful outside of the home in a working environment, very few changes were being made in sex education materials to teach young America that the stereotypical gender roles were no longer the norm. According to Kilander,

“Industry and business have been removing adults, especially mothers, from the routine of the home, in which important educational influences formerly accompanied normal family life. Families have become smaller. And more and more, children and youth are segregated outside of the home into groups about the same age.” 14

The 1967 Anaheim, California “Sex Education Course Outline for Grades Seven through Twelve” notes the same changes in society in the U.S. and even states an effort to create a sex education course that coincides with these changes. Parents and teachers in a citizens advisory committee met, and after “a very thoughtful and thorough study of the whole problem of sex education” devised a revamped program for teaching their students about sex. 15 This school took on a “positive, objective approach” for sex education, and emphasized “developing effective interpersonal relations and attitudes to serve as a specific basis for making meaningful moral judgments.” 16 The planning and preparation behind sex education curricula played a major role in the actual implementation of programs within schools. Not only does Kilander map objectives of both Family Life Education and Sex Education, but he does so beginning as early as preschool. He defends his position of this early-age sex education plan with the top three reasons: “sex education is not as emotional a problem at this age level…” “the child is most likely already beginning to pick up inaccurate information…” “the child accepts sex education more readily and naturally at this age level.” 17 Kilander’s curriculum planning at the preschool age level revolves around the two most popular questions that seem to plague this age group: “What is the difference between boys and girls?” and “how do babies get born?” 18 The first of these two questions shows the beginning of a definite line showing that there is a significant difference between boys and girls.

Kilander continues to point out with the aims of sex education in the early elementary years, that it is important for curricula to emphasize the roles of boys and girls. For example, Kilander writes as his number two aim for sex education in elementary school: “give direction toward male or female role in adult life.” 19 As the years continue in elementary school, more gender-specific goals are defined by the lessons in sex education, like “appreciate efforts of mother and father for family members,” 20 which puts young students in the position to define the differences in the roles that the most influential people in their lives play. In the curriculum for sex education, role-play is often times an integral part in the growth of students and their understanding of specific topics. Kilander writes, “Some of these might pertain to family roles of mothers and fathers, to simple courtesies or ‘manners’ displayed by family members toward one another and by boys and girls toward each other in the classroom, cafeteria, etc.” 21 When speaking of “desirable attitudes,” Kilander discusses examples such as how girls would help “care for a new baby,” for example. Some of the concepts that sex education is meant to make clear for younger students include gender role stereotyping topics. For example, the curriculum emphasizes that “every person needs to have a feeling of belonging,” 22 which is true, and with the lessons in 1960’s sex education classes, the students belong to either a stereotypical male group, or stereotypical female group. Within the lessons of 60’s sex education, there is an extreme emphasis on the differences of boys and girls, their role in the family, and where each individual student belongs in these groups that are defined by a gender stereotyping society.

In 1960’s secondary sex education, the objectives become far more detailed and advanced. Students are expected to learn about sexual intercourse, marriage, “boy-girl and man-woman relationships of the right kind,” and many others. 23 In the Anaheim, California sex education curriculum, the same morals are emphasized. This source specifically focuses on the values of marriage and the more traditional views of dating, sex, and relationships. A great example of this is Appendix III on page 4 with the “Dating Ladder.” It begins at the bottom rung with “children playing together,” and ends with the highest rung and “engagement and marriage.” 24 Learning activities in secondary school sex education classes can range from as simple as finding where body organs are located, to the discussion of making appropriate life decisions. In a test of “attitudes” of the students in the sex education class, some of the questions that students must respond to include “A girl should remember that she is a lady, and should never participate in vigorous sports,” and “A boy could not get serious with a girl who has a reputation of being promiscuous.” 25 Both of these examples give students the opportunity to believe that either of these options are something to agree with, or disagree with. In today’s society, the response would clearly be ‘disagree’ for both of these examples, however, with the lessons of sex education in the 1960’s, all of the emphasis of acceptable gender roles in society led students to agree with both of these statements due to the fact that society was acceptable of the idea that men were bread-winners and women were home-makers. This general idea that was a result of sex education classes during the 60’s is not any different from the perception of gender roles in society through sex education materials in the 1950’s.

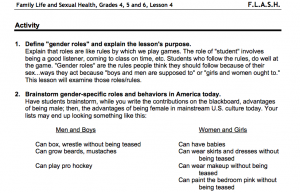

When looking at the changes that occurred between sex education materials from the 1960’s to today, the most significant differences can be seen beginning as early as the late 1990’s. Luker interprets these changes through statistics of women in the working environment: “between 1960 and 1998, the number of ‘high-powered’ professional women leapt from just under 5 percent to over 25 percent.” 26 This dramatic change can also be seen in changes to sex education materials between the 1960’s and today. The Department of Curriculum and Instruction in Montgomery County Public Schools, Rockville, Maryland 8th Grade Health Curriculum from 2005 clearly shows the emphasis in redefining gender roles and no longer only accepting the stereotypical male-female roles. For example, the teaching topics have expanded from only how to act appropriately on a date, to mental health discussions such as “managing stress” to “risk-taking.” 27 The most significant differences between 1960’s sex education materials and today’s materials is the inclusion of an entire lesson dedicated to “gender roles” and “gender identities.” The Maryland 8th Grade Health Curriculum has various examples defining what a stereotypical gender role may be. For example, on page 11, the curriculum defines gender role stereotyping in ways such as “girls are better at English, boys are better at science” or “boys don’t cry, girls do.” The lesson plan then asks students to discuss how these stereotypes are “destructive to the community” and can hinder “the ability of people to accept and respect diversity.” 28 Another main source for teachers of sex education courses today is the website “SexEd Library.” This website shows lesson plans and teacher notes for how to discuss the very sensitive issues of sex and health in 2012. Similar to the Rockville, Maryland curriculum, the SexEd Library has an entire lesson devoted to the understanding and acceptance of various definitions of gender and gender roles. A Society and Culture unit has a lesson called “gender roles”, which is summarized as a:

“lesson [that] helps young people explore the sources of gender role beliefs, learn the similarities and differences between the expectations of each gender, recognize that a person’s beliefs about roles can influence his or her decisions.” 29

These lessons are seen throughout the nation in 21st century sex education materials and in comparing them to 1960’s materials, the most significant change is the inclusion of entire lessons devoted to the discussion of the roles of men and women within society. Due to the beginning of the sexual revolution in the 1960’s, one would expect sex education materials for young students to have changed in regards to what gender roles are acceptable and expected in society. Research shows, however, that that was not the case and many of the same values and gender role expectations remained in sex education materials from the 1950’s to the 1960’s. The most significant changes that one can see in these materials are between the 1960’s and today in the 21st century. Sex education materials are more sensitive towards the changing understanding in society that women are not expected to stay home and raise children for their adult lives, but rather they can have extremely successful careers as well. At the same time, sex education materials today show that men are able to manage a household and raise children without being criticized by society. This redefinition of acceptable gender roles in society is the most significant change in sex education between the 1960’s and today. As the nation continues to change and the acceptance of various definitions of gender and sexual orientation become more widely known, sex education materials will continue to change, and discussions between teachers and students about these topics will become more necessary.

About The Author: Ashley Ardinger is a senior at Trinity College in Hartford, CT and will be graduating this month with a major in Educational Studies and a minor in Music. In Ashley’s near future she will be attending the Columbia Teachers College and getting her Masters in Inclusive Secondary Special Education. Ashley loves to sing and is the director of the Trinity Pipes A Capella group on campus, and is looking forward to beginning a new learning chapter in New York City.

- “Gender Roles,” SexEd Library, 2012, http://www.sexedlibrary.org/index.cfm?pageId=768. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 3. ↩

- “1950’s Sex Education Video,” YouTube video, 1:36, November 17, 2007, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZIssz_RH4s4. ↩

- “Sex Education for Girls Part 2,” YouTube video, 7:24, March 1, 2007, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIltdURp-9Y&feature=relmfu. ↩

- G.G. Wetherill, “Sex Education in the Public Schools,” The Journal of School Health, The American School Health Association XXXI, No. 7 (September, 1961). ↩

- G.G. Wetherill, “Sex Education in the Public Schools,” The Journal of School Health, The American School Health Association XXXI, No. 7 (September, 1961): 237. ↩

- G.G. Wetherill, “Sex Education in the Public Schools,” The Journal of School Health, The American School Health Association XXXI, No. 7 (September, 1961): 239. ↩

- Jeffrey P. Moran, Teaching Sex: The Shaping of Adolescence in the 20th Century (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000), 61. ↩

- Esther D. Schulz, Sally R. Williams, Family Life and Sex Education: Curriculum and Instruction (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1969), 146. ↩

- Esther D. Schulz, Sally R. Williams, Family Life and Sex Education: Curriculum and Instruction (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1969), 147. ↩

- Esther D. Schulz, Sally R. Williams, Family Life and Sex Education: Curriculum and Instruction (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1969), 149. ↩

- Jeffrey P. Moran, Teaching Sex: The Shaping of Adolescence in the 20th Century (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000), 159. ↩

- Kristin Luker, When Sex Goes to School: Warring Views on Sex and Sex Education Since the Sixties (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006), 68. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 7. ↩

- Anaheim Union High School, “Family Life and Sex Education Course Outline: Grades Seven Through Twelve”. Anaheim Union High School District, June 1967, ii. ↩

- Anaheim Union High School, “Family Life and Sex Education Course Outline: Grades Seven Through Twelve”. Anaheim Union High School District, June 1967, iv. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 51. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 52. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 56. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 56. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 60. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 61. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 73. ↩

- Anaheim Union High School, “Family Life and Sex Education Course Outline: Grades Seven Through Twelve”. Anaheim Union High School District, June 1967, 4. ↩

- H. Frederick Kilander, Sex Education in the Schools (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), 155. ↩

- Kristin Luker, When Sex Goes to School: Warring Views on Sex and Sex Education Since the Sixties (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006), 75. ↩

- Department of Curriculum and Instruction: Montgomery County Public Schools, Rockville, Maryland, “Grade 8 Health Education Curriculum,” TeachTheFacts, 2005, http://www.teachthefacts.org/Grade8_Field_Test_Revised.pdf, 5. ↩

- Department of Curriculum and Instruction: Montgomery County Public Schools, Rockville, Maryland, “Grade 8 Health Education Curriculum,” TeachTheFacts, 2005, http://www.teachthefacts.org/Grade8_Field_Test_Revised.pdf, 11. ↩

- “Gender Roles,” SexEd Library, 2012, http://www.sexedlibrary.org/index.cfm?pageId=768. ↩

- “Gender Roles,” SexEd Library, 2012, http://www.sexedlibrary.org/index.cfm?pageId=768.” ↩

- “Gender Roles,” SexEd Library, 2012, http://www.sexedlibrary.org/index.cfm?pageId=768, 4-3 ↩