Educational support programs outside of the classroom have been long known as highly beneficial for improving the educational development and achievement outcomes of youth, especially for those of color who come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. According to a longitudinal study sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, “among the typical after-school care arrangements poor children experience, ASPs (After School Programs) appear unique in their ability to promote academic-related success,” as they found that, “Children characterized by the ASP care arrangement showed significantly higher reading achievement at the end of the school year compared with children in all other patterns of after-school care and were rated by teachers as holding greater expectancies of success compared with children in the other adult/nonadult care pattern” (Carryl, Lord, Mahoney 2005). However, it is also important to note that these programs exist within a larger educational context. The landscape of American education is constantly changing as our society evolves and its needs and priorities shift. Throughout these changes, the overarching goal is to improve our quality of education. One of the means by which many have attempted to advance education outside of the classroom is through pre-college educational programs. These have been known, and supported by research, to be highly instrumental in the educational development and achievement outcomes of youth, and their impacts have shown to be especially significant for students coming from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. Given our constantly shifting educational landscape, the question arises of how are these programs affected by these shifts. Looking particularly at Upward Bound, a federally funded pre-college educational program, this essay investigates whether its goals or approaches have changed, if at all, since its origin in 1965, and if any factors may have pressured it to change.

In searching for changes in the program since its inception, my findings have shown a change in how this overarching objective is reached. This change was found in looking at the target population of the program. Since their inception, they have made a shift from focusing on opening the door to college for qualified but economically disadvantaged students, especially those of color, to emphasizing helping struggling students get on the pathway to that door. They began by giving well performing students, who were potential first generation college students, the necessary support to make sure they attend college. However, about 35 years after it began, they began to pay more attention to the net change in achievement and initiated plans to focus in on helping students who would likely not get into college without their support. This shift was largely influenced by the criticism received by the program on their effectiveness and their actual impact on student performance as opposed to college enrollment. These questions of efficiency had financial implications, as the federal funding for the program is results based. It wasn’t until a financial incentive was added by the Department of Education that the program began to make this shift in target population.

First, to provide background, the Upward Bound program came about in 1965, during the civil rights era, as a result of what Deborah P. Wolfe called “Excluding the Civil Rights Bill, the most significant legislation affecting the American Negro today,”(Wolfe 1965, p. 88) the Economic Opportunity Act. This act was legislated under the “War on Poverty” declared by President Lyndon B. Johnson and his administration (McElroy & Armesto 1998, p. 373). In explaining the circumstances of, and sentiment around, the act during during that time, Wolfe wrote, “When we look at the total picture in American life, we find that of the 9.7 million families in the United States with incomes under $3,000, 7.6 million, or 79 percent, were white and about 2 million, or 20 percent, were Negro. Such statistics bear evidence of the consistency of poverty among Negroes and therefore the concern that all American Negroes should have in alleviating these conditions as made possible through the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964,” (Wolfe 1965). This was indicative of the widely held view of this act being a beacon of hope for the socioeconomic mobility and advancement of the black population, among other minority groups. Upward Bound was the first of the set of programs that came out of this act and the Higher Education act of 1965, which are now known as the TRIO programs, but originally called the Special Programs for Students from Disadvantaged Backgrounds (McElroy & Armesto 1998, p. 373). This program “engages participating students in an extensive, multi-year program designed to provide academic, counseling, and tutoring services along with a cultural enrichment component, all of which enhance their regular school program prior to entering college,” (McElroy & Armesto 1998, p. 375).

For years, this program served as a sort of conveyor belt, which helped ensure that skilled and qualified students from disadvantaged backgrounds had they support they needed to proceed from high school, to college, and then graduate from college (McElroy & Armesto 1998). However, many of their critics argued that the statistical effectiveness of the program was being skewed due to the way students were selected to participate in the program. In 1997, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. (MPR) investigated statistical reports on the program’s effectiveness, in summary of their results, McElroy and Armesto stated, “MPR’s investigations found Upward Bound to have no effect on participants’ high school academic preparation or grades, it concluded that the program had a positive effect on students’ college enrollment,” (McElroy & Armesto 1998). Former TRIO program director, Larry Oxendine, had found in a 2002 draft report the results of a longitudinal study comparing students from similar backgrounds, which found that the program only increased the likelihood of college attendance for “Students who had low expectations of attending college at the start of the study,” who were an anomaly amongst the rest of students in the study.” As Kelly Field further explained, “Oxendine surmised that the reason Upward Bound failed to increase college-going rates for the rest of the participants was because those students would have gone to college anyway. He hypothesized that if Upward Bound were refocused on higher-risk students, its impact on college-going rates would be greater and its limited budget would be spent more effectively,” (Field 2007).

In talking with Education Week Reporter, Sarah Sparks, the vice president at Mathematica Policy Research and co-principal investigator of the federal What Works Clearinghouse stated of Upward Bound, “They were intended to solve a real injustice of students who were academically ready to go to college, but just were low income and needed information… When this started there was not an expectation that everybody would go to college, so why would they focus on struggling students?” (Sparks 2014). Upward Bound partly found that reason through their results-based grant funding, which incentivizes high improvements in the net change of student performance. As their program profile released in 2004 states, “The Department of Education has continued to encourage projects to serve greater numbers of higher-risk students,” (Research Triangle Institute 2004). If their focus remained primarily what they were accused of, which is bringing in participants who are college-bound without them, their results would yield little change in performance amongst these students.

After finding in national evaluations that they were achieving greatest increases in performance in 1999-2000 amongst students at high risk of not finishing high school, “the Department of Education awarded supplemental grants to 184 regular Upward Bound projects to encourage them to select and serve such students over a three-year period,” (Research Triangle Institute 2004). With the adoption of this plan, known as the FY 2000 Upward Bound Program Participant Expansion Initiative, the program had made an official plan to shift towards focusing on students who were likely to not graduate high school or attend college. This plan states, “The Secretary gives absolute preference to applications that meet the following priority… A project funded under this priority must serve a target high school in which at least 50 percent of the students were eligible for the Free Lunch program during the 1998-1999 school year,” (United States Department of Education 2000).

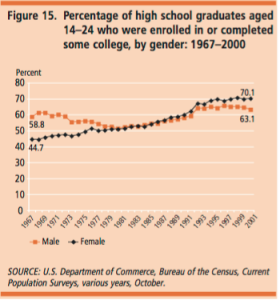

To contextualize this change, we must look that how the issues the program aimed to address have changed over that time period. From the early years of the program in the late 1960s and 1970s, to the turn of the twenty-first century, there were significant changes in parent education levels, youth poverty rates, and college attendance. Youth poverty rates showed the biggest decrease from 1970 to 2001 amongst the group with the highest rates, which is the black population, as the poverty rate for black children under the age of 18 went from 41.5 percent to 30.2 percent (Research Triangle Institute 2004).  This change came along with a general increase in educational attainment amongst all groups. The nation experienced an overall increase in college attendance amongst its citizens from 1967 to 2001, as the number of high school graduates aged 14-24 who enrolled in or completed college rose approximately 4.3 percent f

This change came along with a general increase in educational attainment amongst all groups. The nation experienced an overall increase in college attendance amongst its citizens from 1967 to 2001, as the number of high school graduates aged 14-24 who enrolled in or completed college rose approximately 4.3 percent f or males and 26.4 percent for women. In 1972, only 4 percent of fathers and 3.5 percent of mothers of black children ages six to eighteen had obtained a bachelor’s degree, but by 2002, these numbers rose to 16.5 percent of fathers and 13.9 percent of mothers holding bachelor’s

or males and 26.4 percent for women. In 1972, only 4 percent of fathers and 3.5 percent of mothers of black children ages six to eighteen had obtained a bachelor’s degree, but by 2002, these numbers rose to 16.5 percent of fathers and 13.9 percent of mothers holding bachelor’s  degrees (Research Triangle Institute 2004). These increases in education levels, especially those amongst women and people of color, show an increase in access to higher education for groups who previously lacked access. These changes in the landscape of our society serve as the context in which the Upward Bound program experienced its pressures to address its effectiveness and subsequently lead to a change in target population. When the program began in 1965, we were only ten years removed from the Montgomery Bus Boycott. At this point during the civil rights movement, war was being waged against the issue of a lack of access to institutions for blacks and other marginalized groups, and the program was intended to address this inequality under the Economic Opportunity Act. As our society improved in educational outcomes since the 1960s, the educational needs and priorities of the country shifted. The continued existence of race-based, class-based, and gender-based educational achievement gaps provided for an environment that would call for educational programs to place focus on helping low performing students raise their achievement level.

degrees (Research Triangle Institute 2004). These increases in education levels, especially those amongst women and people of color, show an increase in access to higher education for groups who previously lacked access. These changes in the landscape of our society serve as the context in which the Upward Bound program experienced its pressures to address its effectiveness and subsequently lead to a change in target population. When the program began in 1965, we were only ten years removed from the Montgomery Bus Boycott. At this point during the civil rights movement, war was being waged against the issue of a lack of access to institutions for blacks and other marginalized groups, and the program was intended to address this inequality under the Economic Opportunity Act. As our society improved in educational outcomes since the 1960s, the educational needs and priorities of the country shifted. The continued existence of race-based, class-based, and gender-based educational achievement gaps provided for an environment that would call for educational programs to place focus on helping low performing students raise their achievement level.

Overall, these findings have shown that a shift did indeed occur in the target population of the Upward Bound program, as the Department of Education placed explicit priority on serving students who at risk of not graduating high school and continuing to college. It also showed that a shift in social context, criticism on efficiency, and financial incentives have been the key factors in causing the Upward Bound program to begin this shift in its target population. The changing needs and priorities of American education that developed as access to higher education increased provided a propitious setting for the concerns and criticisms of the programs methods to be addressed. With these factors in place, the addition of a financial incentive served as the last needed component to formalize a shift in its target audience. The ways by which this program made its shift in approach also serves an example of how financial incentives tend to be the selling point of making changes that are viewed as beneficial for society. Which leaves us with the question, what level of importance do financial incentives hold when pushing for progressivity in educational programming?

References:

Carryl, Erica. Lord, Heather. Mahoney, Joseph L. &. (2005). An Ecological Analysis of

After-School Program Participation and the Development of Academic Performance

and Motivational Attributes for Disadvantaged Children. Child Development, 76(4),

811–825.

Field, K. (2007). Are the Right Students ‘Upward Bound?’. Chronicle Of Higher Education,

53(50), A20-A21.

McElroy, E. J., & Armesto, M.. (1998). TRIO and Upward Bound: History, Programs, and

Issues-Past, Present, and Future. The Journal of Negro Education, 67(4), 373–380. http://doi.org/10.2307/2668137

Research Triangle Institute. Cahalan, Margaret W. Curtin, Thomas R. (2004). A Profile of the

Upward Bound Program: 2000-20001. United States Department of Education Office of Postsecondary Education Federal TRIO Programs.

Sparks, Sarah D. (2014). ‘Lucky Few’ Served By War on Poverty College Programs. (cover

story). Education Week, 34(11), 1-15.

U.S. Bureau of Census. (2001). March Current Population Survey, various years as reported in

the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Condition

of Education.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. (2002). Current Population Surveys,

Historical Poverty Tables, Table 3. Poverty Status of People, by Age, Race, and

Hispanic Origin: 1959-2002.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. (2002). Current Population Surveys,

1967-2001.

U.S. Department of Education. (2000). Office of Postsecondary Education Upward Bound

Participant Expansion Initiative and Inviting Applications for Supplemental Awards

for Fiscal Year (FY) 2000. Part V. p 45699.

Wolfe, D. P.. (1965). What the Economic Opportunity Act Means to the Negro. The Journal of

Negro Education, 34(1), 88–92. http://doi.org/10.2307/2294300