Tackling head injuries from several angles

By Jim H. Smith

Saturday, October 11, 2014, featured a cider-crisp snap in the air—perfect football weather. Trinity, riding a 52-game home-win streak, was hosting the Tufts University Jumbos. The Bantams had begun the season with victories over Colby, Williams, and Hamilton by an impressive cumulative score of 89–14.

Mike Weatherby ’14, an American studies major from Atlantic City, New Jersey, was on his game that afternoon. The speedy, hard-hitting outside linebacker was a Trinity graduate student at the time; since he had missed his first year while recovering from shoulder surgery, he was playing out his final year of eligibility. With back-to-back sacks in the third quarter, he buried the Jumbos deep in their territory, forcing them to punt. Then, late in the game, he capped his big afternoon with an interception. But it turned out to be something of a Pyrrhic victory.

“Typically, I was an emotional player,” says Weatherby, a team captain, “but after the interception, I just felt foggy. I knew something was off.”

Weatherby was well aware of the risk for head injuries that all football players accept as part of the game. What felt strange, though, was that he couldn’t remember hitting his head during the game. And no one had tackled him particularly hard.

Trinity went on to win 35–14. But Weatherby was diagnosed with a concussion and had to sit out for two games. In the second of those contests, he could only watch from the sidelines as Middlebury soundly defeated his team, winning by 20 points and snapping the 53-game home-win streak.

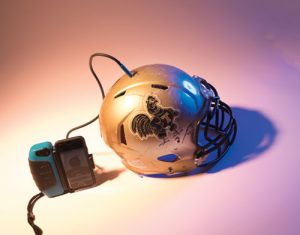

A Trinity football helmet connected to HelmetFit, a new inflation system that helps maintain a consistent fit for each player.

Photo: Ed Cunicelli

As things turned out, though, Weatherby’s concussion inspired him to think about how the air bladders inside players’ helmets are inflated. At the time of his injury, helmets were inflated mostly according to how well players thought the helmets fit. On any given game day, a player might be wearing a helmet inflated differently from the last time he’d worn it. It was all subjective.

Weatherby knew that while a tight fit maximizes a helmet’s protection, some players preferred wearing their helmets loose. So, in the years since his graduation—while he worked in real estate and then joined the Tampa Bay Rays baseball organization in a promotional role from 2015 to 2017—he has devoted his spare time to designing HelmitFit, a new inflation system that would enable trainers to precisely fit each player’s helmet, day after day.

Weatherby says he now has commitments from prominent Division I universities, including Syracuse and Ohio State, to use the system. “Our goal,” Weatherby asserts, “is to consistently find the perfect balance, for every player, between comfort and a nice, snug fit.”

MINING THE DATA

In recent years, news media have focused a glaring spotlight on the grim, and growing, roster of former NFL players suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a debilitating and incurable disorder afflicting many who have endured multiple brain injuries. In the ensuing dialogue, football and concussions have become almost synonymous.

But it’s important to note that not every concussion leads to CTE. Nor are concussions in sports limited to the gridiron. During the 2016–17 academic year, for instance, Trinity reported eight concussions. Though football accounted for four, two occurred in men’s soccer, and one each in men’s basketball and men’s ice hockey. No matter where or how concussions occur, Trinity is seeking better ways to diagnose, monitor, manage, and prevent them.

“Athletic training has evolved in response to the risk of head injuries,” says Scot Ward, Trinity’s director of sports medicine. “Regardless of the sport, we’re at all practices and events, and we treat any head injury as serious. We ask all of our student-athletes to participate in a baseline cognitive evaluation at the beginning of the year. Then we test the recovery of any athlete who has been concussed against his or her baseline. We’re very circumspect about how long a player will be sidelined. With concussions, we take no chances.”

Imran Hafeez, M.D., who has been involved with Trinity athletics since 2011 and has served as a team physician since 2015, says, “Thanks to our athletic trainers, student-athletes have a pretty good understanding of concussions. They understand the importance of complete recovery.

“In the past, concussions were addressed by requiring patients to pretty much put their lives on hold,” he adds. “In recent years, however, treatment has changed to normalizing life as much as possible, as long as the patient isn’t ignoring symptoms. Research has shown that this approach helps to speed recovery. So we don’t ask students to stop attending classes, but we ask them to stop if they experience symptoms. Research has also shown that some low-level aerobic physical activity can also help people recover.”

“In the past, concussions were addressed by requiring patients to pretty much put their lives on hold,” he adds. “In recent years, however, treatment has changed to normalizing life as much as possible, as long as the patient isn’t ignoring symptoms. Research has shown that this approach helps to speed recovery. So we don’t ask students to stop attending classes, but we ask them to stop if they experience symptoms. Research has also shown that some low-level aerobic physical activity can also help people recover.”

The big issue with concussions, says Hafeez, isn’t whether an athlete has one. It’s how the injured person deals with it. “The rule of thumb, if you have a concussion, is don’t ignore it,” he says, “and don’t put yourself in a situation to get another one until you’ve been cleared.” While there are no clear predictors for recovery—each concussion is unique—80 percent of people recover fully and usually within a month. Student-athletes, most of whom are in excellent health, often recover more quickly than that.

Last year, Ward and a group of Trinity staff attended a New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC) Concussion Summit in Maine. The event was hosted by Paul Berkner, medical director of Health Services at Colby College and founder of the Maine Concussion Management Initiative (MCMI), a program launched in 2009 to promote awareness about concussions and to conduct research.

“The MCMI is partnered with the NESCAC and more than 100 Maine high schools,” says Berkner. “Three years ago, we began receiving concussion reports from all of the NESCAC schools. We’re looking for risk factors for prolonged recovery. Our database is still small. Currently, we have NESCAC data on about 1,200 concussions. By collecting and cross-referencing the data from these reports, we hope to better understand concussions and eventually reduce the number.”

UNDERSTANDING, PREVENTING

Back at Trinity, several concussion-related studies are being conducted under the supervision of Sarah A. Raskin, professor of psychology and neuroscience, whose research focuses primarily on understanding the symptoms unique to individual brain injuries and the development of management techniques to improve quality of life for people who’ve suffered them.

Olivia DeJoie ’17, a candidate for an M.A. in neuroscience, is exploring brain injuries as they relate to incidences of domestic violence. Raskin says, “This work is important because studies have shown it’s not uncommon for women to sustain mild brain injuries during domestic disputes and be completely unaware of it.”

Chloe White ’18 is studying why a small number of concussion victims endure lasting effects, including attention and memory deficits. Working with Trinity students who have a history of concussions, she is evaluating the effect of diagnosis threat—fear of concussion-related inability to perform well in situations where intellectual capacity is required.

Zachary Bitan ’17, also an M.A. candidate, is working with Matthew Solomito, Ph.D., of Connecticut Children’s Medical Center on the development of a sophisticated tool called the Elite Balance Protocol (EBP). The EBP goes beyond the static balance test, an examination of an individual’s balance that has long been the standard for evaluating the progress of recovery from a concussion. Bitan says recent research has shown the static test is not sophisticated enough.

“The EBP asks patients to perform two tasks at once—a balance test and a cognitive load test,” Bitan says. “This test is more sensitive to the kinds of deficits seen after concussions. It is Dr. Solomito’s hope that the EBP will become a clinical tool that can aid physicians and sports medicine personnel in more effectively tracking individual recovery progress.”

And then there is Mike Weatherby, the former Trinity football player who suffered a concussion back in 2014. Two years ago when he had a HelmetFit prototype, the first place he asked to test it was his alma mater. The test went exceptionally well, says Mark Moynihan, athletic equipment manager for men’s sports. So well, indeed, that the device is routinely used at Trinity to fit helmets and to maintain ideal air-bladder pressure.

Based on Trinity’s feedback, the device—designed by the Bresslergroup, a prominent Philadelphia engineering company—and its software—created by BrickSimple, a Pennsylvania software development company—were tweaked. A new prototype was successfully tested last year by seven schools, as well as the San Francisco 49ers.