Home-schooling can be a challenging topic to research because it exists outside of most governmental education data-collection systems. What are current estimates of the number (and percentage) of children who are home-schooled in the US, and has this rate grown over time? Describe your search strategy to find reliable estimates, and if sources disagree, briefly explain how and offer some reasons why.

The practice of homeschooling students has, in fact, become more and more popular over the past decade. In 1999 the National Household Education Surveys Program found that across the United States, about 1.7 percent of students, approximately 850,000 individuals, were homeschooled. By 2003, the percentage of students studying at home rose to 2.2 percent. In the 2005-2006 school year, between 1.9 and 2.4 million students were homeschooled. The number of youth educated at home continues to rise. However, current, up-to-date data was difficult to locate despite my best search efforts, most likely due to the difficulty posed to researchers by the collecting of this information.

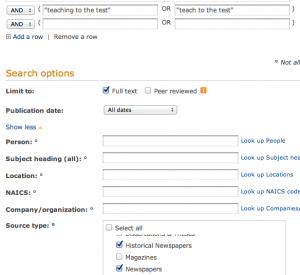

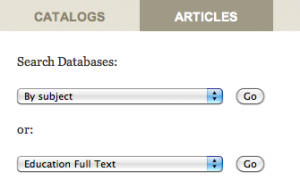

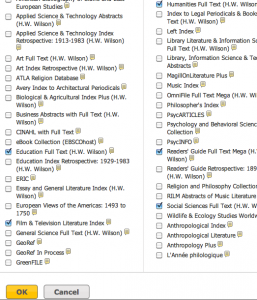

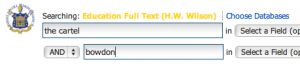

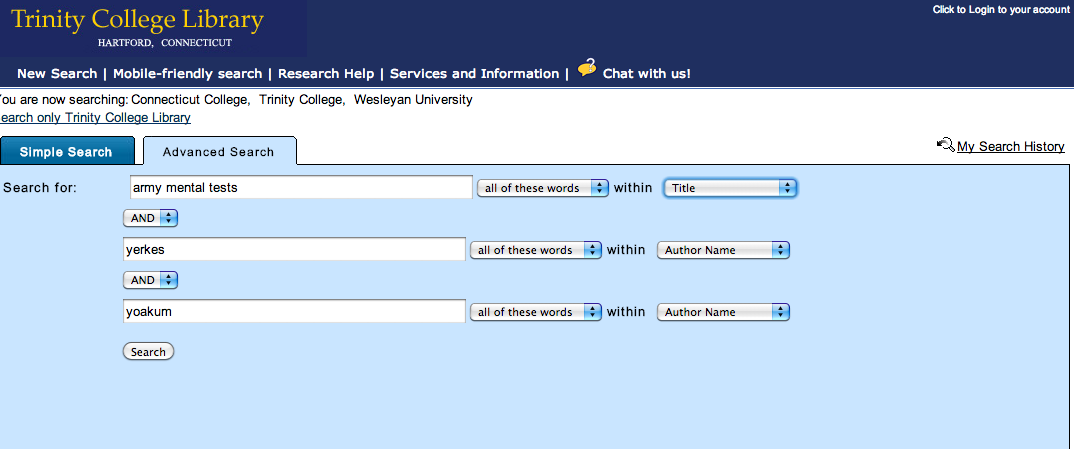

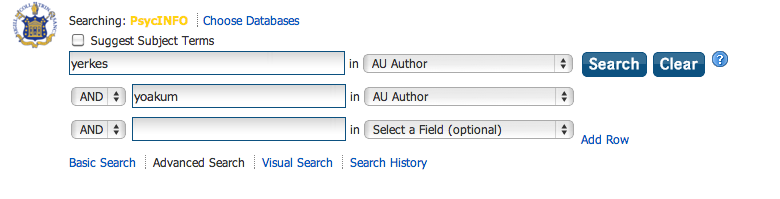

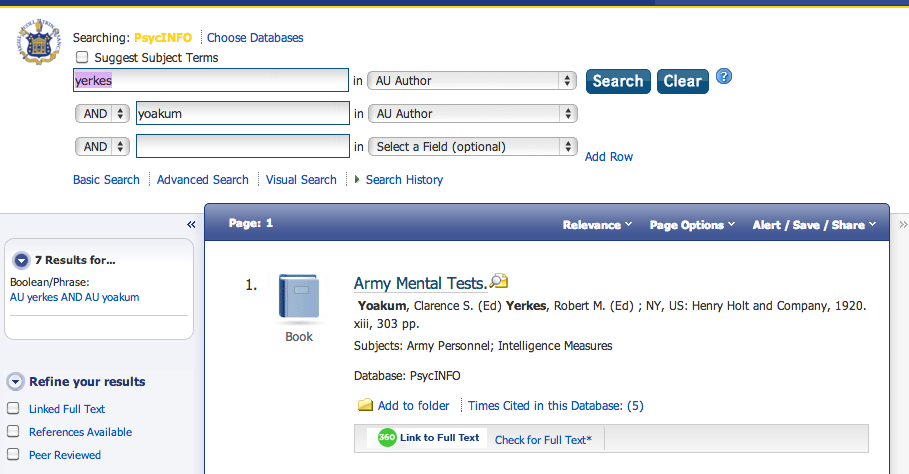

To start, I searched the terms “homeschooling in the united states” on Google Scholar, which led me to a number of studies by the National Household Education Surveys Program that involved collecting data about homeschooling in the United States. These sources provided some statistical data concerning the number of students in the United States being homeschooled in a given year, and the percentage of all U.S. students that they constitute. My next search, “current homeschooling rates,” was not quite as successful. It proved far more difficult for me to find information about current rates of homeschooling in the United States. In fact, many of the sources I found with data about home schooling did not discuss information that was current at the time they were published: for example, one work was published in 2001 and referred to 1999 statistics.

To start, I searched the terms “homeschooling in the united states” on Google Scholar, which led me to a number of studies by the National Household Education Surveys Program that involved collecting data about homeschooling in the United States. These sources provided some statistical data concerning the number of students in the United States being homeschooled in a given year, and the percentage of all U.S. students that they constitute. My next search, “current homeschooling rates,” was not quite as successful. It proved far more difficult for me to find information about current rates of homeschooling in the United States. In fact, many of the sources I found with data about home schooling did not discuss information that was current at the time they were published: for example, one work was published in 2001 and referred to 1999 statistics.

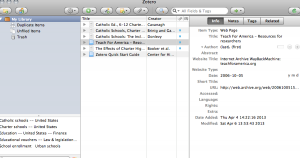

Next, I moved to WorldCat and began my search with various terms, “current homeschooling rates,” “homeschooling in the US,” and “2012 home education.” Most of the information I found included information on tried and true homeschooling practices, books discussing specific groups within the homeschooling community (for example, Write these laws on your children : inside the world of conservative Christian homeschooling, a book by Robert Kunzman), and when I searched “2012 home education,” I was led to a series of sources that equated to high level ‘how-to’ guides and self-help books. Unfortunately, none of these sources were geared toward statistical analysis or data collection about the rates of homeschooling. In desperation, I turned to Wikipedia – which, perhaps, I should have done at the start. According to the “Homeschooling in the United States” page, approximately 2.9 percent, or 2 million, United States students are currently being homeschooled. I used some of the cited references from the Wikipedia page to find out a bit more about current rates.

A Wikipedia reference led me to a brief issued by the National Center for Education Statistics from December 2008. According to the Parent and Family Involvement in Education survey conducted by the NHES, 1.5 million United States students were engaged in home education in 2007. This brief led me to search for the National Center for Education Statistics on Google where I found the most recent version of Projections of Education Statistics to 2012. Unfortunately, “Neither the actual numbers nor the projections of public and private elementary and secondary school enrollment include homeschooled students because more data are required to develop reliable projections” (Projections 1).

A Wikipedia reference led me to a brief issued by the National Center for Education Statistics from December 2008. According to the Parent and Family Involvement in Education survey conducted by the NHES, 1.5 million United States students were engaged in home education in 2007. This brief led me to search for the National Center for Education Statistics on Google where I found the most recent version of Projections of Education Statistics to 2012. Unfortunately, “Neither the actual numbers nor the projections of public and private elementary and secondary school enrollment include homeschooled students because more data are required to develop reliable projections” (Projections 1).

It seems to me that the most current information available on homeschooling statistics is lagging by a few years. The sources that I found did not discuss the homeschooling rate at the times they were published, but instead, the data from approximately three years prior. Nevertheless, I was able to uncover the fact that the practice of homeschooling has become more prevalent over the past decade and the number and percentage of students being educated at home has increased.

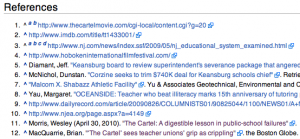

Works Cited

Bielick, Stacey, Kathryn Chandler, and Stephen P. Broughman. “Homeschooling in the United States: 1999.” (2001). Education Resources Information Center. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=ED455926

Princiotta, Daniel, Stacey Bielick, and Chris Chapman. “1.1 Million Homeschooled Students in the United States in 2003. Issue Brief. NCES 2004-115.” National Center for Education Statistics (2004).

“Projections of Education Statistics to 2021 – About This Report.” Projections of Education Statistics to 2021 – About This Report. National Center for Education Statistics, n.d. Web. 12 Apr. 2013. <http://nces.ed.gov/programs/projections/projections2021/>.

Ray, Brian D. “Research Facts on Homeschooling. General Facts and Trends.” National Home Education Research Institute (2006). Education Resources Information Center. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/detail?accno=ED494583