Spiritual Libertarianism

On April 6, Mark Silk gave the following talk at a Boston College colloquium titled “Why Libertarianism Isn’t Liberal.”

Thirty years ago, when I was in the process of transforming (or should I say degenerating) from a medieval historian into a journalist, I undertook a freelance assignment from the Boston Globe to write a series of profiles of notable academics – one of whom was the late Robert Nozick, professor of philosophy at Harvard, a bit of a wild and crazy guy, and the most philosophically sophisticated libertarian in the country. In preparation for this colloquium I thought I’d exhume that profile and, if I do say so myself, it stands up pretty well.

But one line jumped out at me as out of date; to wit: “In matters of freedom, American culture provides for a certain division of labor, whereby the conservatives uphold free markets and the liberals bear cudgels for free expression and liberated life styles.” Nowadays, the liberals are no longer worrying so much about free expression and while the conservatives are still upholding free markets, they have extended their libertarian outlook beyond economic behavior.

For example, in his 1994 conservative polemic Dead Right, David Frum takes after William Bennett for subtitling The De-Valuing of America, his 1992 conservative polemic, The Struggle for Our Children and Our Culture. “What is the locution ‘our children’ doing in Bennett’s mouth?” asks Frum. “The phrase contains the thought that one’s obligation to all the other children in the country is similar in nature to one’s obligations to one’s own; that a purely political bond—that between citizens of one nation—can resemble in some meaningful way the biological bond between parent and child.”

Since then, Frum has drifted away from this kind of libertarianism, but his book marks a societal shift that has recently been spelled out by Robert Putnam in his new book, Our Kids: the American Dream in Crisis. Here’s Putnam talking about the book a month ago with NPR’s Scott Simon:

When I was growing up in Port Clinton and my parents talked about doing things for our kids – when they said, you know, we’ve got to pay higher taxes so that our kids can have a swimming pool or a new French department or whatever – by the word, our kids, they did not mean my sister and me. They meant all the kids in town. And what’s happened over the last 20, 30, 40 years is that our sense of what counts as our kids has shriveled.

Contra Dead Right, I would argue that the political obligation to the children in our community, nation, and world is similar to the biological tie between parent and child. And I think that view still prevails in the precincts of the Democratic Party, as perhaps evidenced by Hillary Clinton’s use of the well-traveled proverb, “It takes a village to raise a child.” But in that other Party, not so much.

Here is Fox News’ Andrea Tantaros talking with Bill O’Reilly about an alleged downside to government programs to make children healthier. Saying “the road to hell is often paved with good intentions,” Tantaros claims that these are “causing mental problems” and that kids will develop eating disorders because of them.

“Oh, Andrea, come on!” O’Reilly expostulates. “One or two kids are gonna have an eating disorder no matter what you do. It’s the greater good that must be served.” “The greater good!” explodes Tantaros, pointing at O’Reilly. ‘There’s the People’s Republic of Massachusetts oozing out on the couch.”

Whoa!

Of course, Bennett and Reilly are Catholics of a certain generation who for all their ideological conservatism have retained the teaching of their Church articulated last month by Pope Francis: “A society can be judged by the way it treats its children.” I presume that Tantaros, the daughter of Greek immigrants, is or was Greek Orthodox – but more importantly, she’s a child of the Reagan era three decades younger than Bennett and O’Reilly.

The enthusiasm for Rand Paul (and before him his father) among the younger generation of conservatives is plain for all to see, and it has infected even old conservative fogies like George Will. In a word, conservatives have moved toward a philosophy that is explicitly hostile to any public policy that smacks of concern for “our children”—ergo, pejoratively, The Nanny State.

I will consider that philosophy, libertarianism, to be what the contemporary libertarian thinker Tibor Machan defines as “the view that the task of politics is liberty, nothing more or less, and the task of virtue, human excellence or happiness, is a task that only the individual on his own can strive to fulfill either alone or in personal and voluntary association with others, never by force or coercion.”

There are, of course, alternative views of the task of politics, including not only human excellence and happiness but also social welfare and justice and harmony. But for purposes of this colloquium, I propose that we consider the libertarian view to be opposed to what Catholics tend to call the common good – a complex political undertaking that aims at a number of the above tasks, and which therefore must find a balance among them. Forgive me if I neologistically call this view “common-goodism.”

It’s important to recognize that while libertarianism and common-goodism may each have a proclivity for certain public policies, they are not policies themselves but rather ways of advancing, justifying, or rationalizing them. When Nozick says that the government should not be in the business of preventing “capitalist acts between consenting adults,” he is making a libertarian argument for capitalism. When Joseph Schumpeter argues that capitalism advances morality, he is not making a libertarian argument for it.

“Our bodies, ourselves” is a libertarian argument for abortion; protecting poor women from the hardships of unwanted pregnancies is not. Minimizing pain and suffering is not a libertarian argument for physician-assisted suicide; claiming a right to terminate one’s life whenever one wants to is.

What makes a libertarian a libertarian is, as Machan indicates, the privileging of liberty over all other political ends, and a consistent libertarian will do this across all realms of political activity. But as my old profile of Bob Nozick suggested, across-the-board libertarianism has not been the rule, at least in this country.

Traditionally, we’ve had economic libertarians, who embrace the Austrian school of economics; civil libertarians, who identify with the ACLU; and moral libertarians, sometimes known as libertines. The distinctively new development is what I propose calling spiritual libertarianism.

This is a form of libertarianism that sets as its highest political task not free markets or free speech or (let us say) making the country safe for sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll, but the free exercise of religion. This new spiritual libertarianism has, in the past decade, established itself on the American right.

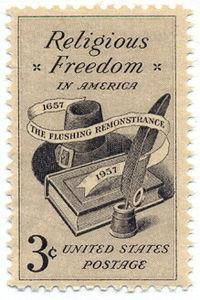

The story of the valorization of religious freedom among conservatives is an interesting one, particularly since within pretty recent memory liberals were the religious freedom stalwarts. For them, providing a means for religious minorities—Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, the Amish—to gain exemptions from legal injunctions was an important dimension of civil liberty, and part and parcel of the rights revolution in American jurisprudence.

Under the circumstances, then, it was no surprise that liberal justices were the ones on the Supreme Court who opposed Justice Scalia’s decision in Employment Division v. Smith, which determined that neutral laws of general applicability could, ipso facto, not violate the Free Exercise clause; i.e. that you couldn’t go get a court to protect your free exercise rights against a law or regulation that applied neutrally to everybody.

This decision led, of course, to the passage of the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which was designed to make the Court revert to its pre-Smith standard of strict scrutiny, requiring the government to demonstrate a compelling state interest in the law or regulation and to show that this interest was being advanced by the least restrictive means.

The coalition that made RFRA happen was led by the dean of liberal religious lobbyists, David Saperstein of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism (now our Ambassador for Religious Freedom). The bill, which passed Congress almost unanimously, was enthusiastically signed into law by President Clinton.

Four years later, the Court swatted down this intrusion on its judicial prerogatives in Boerne v. Flores, but ever since it has sought to limit the reach of Smith without actually reversing it. (Beware the wrath of Nino!)

Because my time is short, let me cut to the chase and say that in his Smith decision Scalia quite intentionally threw Free Exercise into the political arena, saying to religious objectors: “Look, if you want an exception from a neutral, generally applicable law, make your case in legislative bodies.”

Subjecting the constitutional right of free exercise to majoritarian decision-making seemed like a really bad idea to civil libertarians, but most conservatives had no problem with it, I figure because they didn’t imagine that they’d ever lack the political clout to get the exceptions they wanted. They began to have problems when they stopped getting those exceptions. Suddenly, religious freedom was under assault as never before in American history.

Spiritual libertarianism was on display this year in the run-up to passage of Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act, so much so that it extended its reach beyond religion in a way analogous to conscientious objection during the war in Vietnam. Here, for example, is an excerpt from a blog post by conservative activist Monica Boyer, featured on the Indiana Tea Party website in January:

The media has wrongly portrayed this bill to be only about gay marriage. This couldn’t be further from the truth. This Freedom of Conscience bill was designed to protect those who want the freedom of conscience when it comes to healthcare decisions, as well as organizations such as religious charities, businesses who have convictions, colleges with faith statements for students and employees, and so much more. The Indiana RFRA is not only for those be [sic] religious. As my friend Jesse Bohannon said, “Even an Atheist has a right to refuse to do something that is morally repugnant!”

Hoosiers should not be required to provide a service, produce a product, rent out property, or be forced to do business with someone if the service goes against their conscience. Religious or not. Contrary to the hype the media is spewing, this is not a theocratic bill. It is a FREEDOM bill. Freedom for everyone, not just some.

It’s worth noting that the Indiana Catholic Conference, which supported the bill, gave at least lip service to a more balanced philosophy. The bill, the Conference said in a statement,

establishes a legal standard that protects state interests as well as individuals and religious institutions. When there is a compelling state interest in the law or regulation, it must be done in the least restrictive manner thus protecting both [sic] the common good while respecting the conscience and religious freedom of all affected.

And after the national firestorm over the Indiana law broke out, the state’s Catholic bishops said in a statement, “We urge all people of good will to show mutual respect for one another so that the necessary dialogue and discernment can take place to ensure that no one in Indiana will face discrimination whether it is for their sexual orientation or for living their religious beliefs.”

I’m afraid, however, that spiritual libertarianism is alive and well in the American Catholic Church. This is, for the historically conscious, somewhat ironic, given how late the Church came to the modern world’s religious freedom party. Indeed, in the early 1990s the American Catholic bishops were latecomers to the RFRA coalition because they feared that in a hoped-for post-Roe v. Wade world, someone would try to use the act to assert a Free Exercise right to abortion. But in recent years, religious freedom has been promoted as the ne plus ultra of the American democracy. As the bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee for Religious Liberty put it in 2012, it is “our most cherished freedom. It is the first freedom because if we are not free in our conscience and our practice of religion, all other freedoms are fragile.”

In practice, this spiritual libertarianism can be found in the Catholic lawsuits opposing the Affordable Care Act’s contraception mandate, which manifest a singular unwillingness to acknowledge common good considerations on the other side. As Michael Sean Winters wrote the other day:

[S]omeone should tell the Little Sisters of the Poor that their conscience should not be troubled by filling out a form that exempts them from having to provide contraception coverage to their employees. Instead, we have bishops who suggest same sex marriage is a civilizational threat, which it is not, and who encourage the Little Sisters to think that signing a form is material cooperation with evil.

The Fortnight for Freedom has become the Church’s annual festival of spiritual libertarianism. Why not, say, a Fortnight for Immigration Reform?

To my way of thinking, the goal of balancing religious liberty and common good considerations has been on display most clearly in Utah’s recent anti-discrimination legislation, which was not merely backed by, but negotiated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. There, as in Indiana, the Catholic Church seems to have held back, and may even be said to have supported the bill. At least that’s how I read this sentence reporting on it in the Intermountain Catholic, the diocesan newspaper:

The bill represents many hours of work with leaders of the Church Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and LGBT (lesbian, gay, bi-sexual and transgender) advocacy groups to create a state law that strikes a fair and just balance between providing for these basic needs and protecting the rights of people of faith to exercise their beliefs.

By contrast, the Catholic Church actively opposed a comparable anti-discrimination bill in Wyoming, calling it “an unconstitutional infringement on a fundamental constitutional right.” Last month, that bill failed. I’ll just conclude by saying that libertarianism, in its spiritual form, is very much at war with common-goodism in the Church today.

You have done a good job in presenting the standard leftist mantra but this view of the common good is so frighteningly politically correct. What you want is for certain rights to one’s property to be trumped for the collective “common” good.

I find your attempts to make libertarianism at “war” with the common good to be unpersuasive. What its at war with is your particular and fringe view of group rights. If a property owner who does not believe in same sex marriage refuses to cater to such a wedding you would have them surrender that right because “common goodism” is the prevailing leftist dogma.

I shouldnt be surprised but its still frightening that there are still academics who still write this kind of stuff with a straight face.

Never mind I reread your bio at another site. You are no longer an academic. That’s Good. I stand corrected.