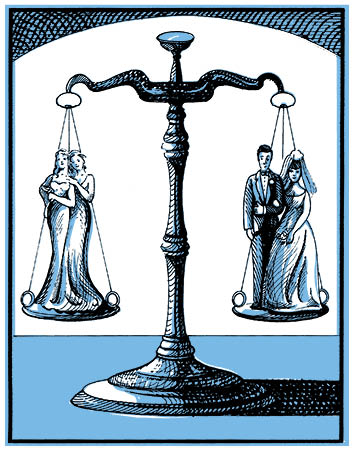

Same Sex Marriage Comes to Alabama

On March 12, 2014, Alabama Circuit Court Judge Karen Hall rejected a petition for divorce from Shrie and Kirsten Richmond, two women who were married in Idaho in 2012. Granting them a divorce, Hall wrote was “not pursuant to the laws of this state.”

“I have a lot of faith in the court system, I have a lot of faith in Judge Karen Hall and I believe she ruled the only way she is able to given the current state of the law in Alabama,” Patrick Hill, Shrie Richmond’s lawyer, told the Birmingham Times. Hill went on to say that he intended “to pursue this as far as I can to see to it that the law that prevents my client from getting a divorce is reversed, and the divorce case is given back to Judge Hall.”

Two months later, Cari Searcy and Kimberly McKeand, a same-sex couple married in California, filed suit in federal court challenging the Alabama law that banned adoption by same-sex couples after Searcy was prevented from legally adopting McKeand’s eight-year-old son. In 2012, their adoption petition had been rejected by Mobile County probate judge Don Davis as a violation of the state’s ban on same-sex marriage – a ruling upheld by the Alabama Court of Civil Appeals.

On Friday, February 6 of this year, both sets of petitioners got good news when Callie Granade, a federal judge in the Southern District of Alabama, ruled the state ban unconstitutional under the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the 14th Amendment. The same day that Granade issued her ruling, the Richmonds resubmitted their request for an uncontested divorce. But the course of same-sex marriage in Alabama did not run smooth.

Two days later – at 8:17 Sunday evening – Chief Justice Roy Moore of the Alabama Supreme Court sent an email to the state’s probate judges ordering that “effective immediately, no probate judge of the state of Alabama nor any agent or employee of any Alabama probate judge shall issue or recognize a marriage license that is inconsistent with Article 1, Section 36.03, of the Alabama Constitution or § 30-1-19, Ala. Code 1975.” In Alabama, probate judges are responsible for distributing marriage licenses.

The email put Moore in the national spotlight – for the second time.

In 2001, after being elected chief justice, Moore arranged for a 2.6-ton granite rock engraved with the Ten Commandments to be placed in the state judicial building in Montgomery. This resulted in a federal court case that found the monument in violation of the First Amendment’s ban on religious establishments.

After Moore refused to obey a federal judge’s order to remove the monument, he was himself removed from office by the Alabama Court of the Judiciary. In 2012, the voters of Alabama elected him to the position again.

Alabama has a history of ignoring federal orders in the name of states’ rights. Most notoriously, Gov. George Wallace stood at the doors of the University of Alabama a half century ago in a symbolic attempt to prevent two African-American students from enrolling. That history weighed heavily on the state’s leading opinion writers.

Calling Moore an “activist judge” and a “grandstanding politician,” the Anniston Star declared:

“Alabama is back to its embarrassing past, all thanks to Moore. His rejection of the supremacy of federal courts was tried by countless Alabama politicians and judges in the past, most notably in refusing to grant full citizenship rights to African-Americans for more than 100 years. In case after case, the argument that Alabama could trump federal court orders was demolished. Each time, Alabama’s reputation suffered another indignity. Each time, Alabama appeared as a small-minded place. Each time, sadly, an Alabama huckster politician scored some points with a devoted following in love with demagoguery.”

Similarly, the editorial board of the Alabama Media Group (comprising the dailies in Birmingham, Huntsville, and Mobile) lamented:

“Unfortunately Alabama remains a state where an obstructionist Supreme Court judge can delay action directed by a federal court. When he told probate judges to ignore a federal judge’s order legalizing same-sex marriage, Roy Moore unnecessarily blocked the doors of some Alabama courthouses and reinforced every national stereotype of an obstructionist Alabama that some here have worked for decades to overcome.”

J.D. Crowe, the Media Group’s cartoonist, portrayed Moore clutching two thunderbolts and saying “NOT ON MY WATCH” as he blocked a door labeled “21st century.”

The morning after Moore issued his order, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a request from Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange to stay Granade’s order – leaving the probate judges to decide for themselves whether to obey a federal court or the state’s top judge. “The Chief Justice has explained in a public memorandum that probate judges do not report to me,” Strange said. “I advise probate judges to talk to their attorneys and associations about how to respond to the ruling.”

Gov. Robert Bentley issued a statement saying he wouldn’t punish them either for issuing or not issuing marriage licenses to gay couples. The result was a predictable checkerboard.

At the Mobile County courthouse, Robert Povilat told the AP’s Kim Chandler and Jay Reeves, “We sat and waited all day for them to open a window. They never did.” Over the next several weeks, 43 of Alabama’s 67 counties issued same-sex marriage licenses, according to one count.

On February 20, even as Moore continued to insist that probate judges refuse to carry out Granade’s order, Bentley told Politico, “We are a nation under laws. We may not always agree with them, but we obey them.” He would, he said, “never do anything to disobey a federal court ruling.”

Then on March 3 the rest of the Alabama Supreme Court stepped up to support their leader, issuing a 7-1 opinion (with Moore abstaining) that forbade probate judges from providing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The 148-page opinion took the position that “state courts may interpret the United States Constitution independently from, and even contrary to, federal courts.”

“As it has done for approximately two centuries, Alabama law allows for ‘marriage’ between only one man and one woman,” the court said. “Alabama probate judges have a ministerial duty not to issue any marriage license contrary to this law. Nothing in the United States Constitution alters or overrides this duty.”

At once, the probate judges stopped issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The actual legal situation was murky.

“Roy Moore–while he gets some important things wrong–is right that state court judges don’t have to follow lower federal judges’ decisions,” American University law professor Amanda Frost told the ABA Journal February 12. In an article published this year in the Vanderbilt Law Review, Frost made clear that the Supreme Court has never determined how much weight state courts should give lower federal court rulings, outside of litigation regarding habeas corpus (the right of detainees to obtain relief from unlawful imprisonment).

But Frost said she considered that in issuing marriage licenses probate judges were acting in an executive rather than judicial capacity, and thus were obliged to follow a lower federal court ruling.

After the Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling, Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr., a law professor at the University of Alabama, told the New York Times that while the decision was technically valid, a sense of “comity” and “respect” usually prevented such actions. “If state supreme courts routinely went out of their way to reject the precedents of their local lower federal courts, it would be conducive to complete chaos, and the system of dual courts would collapse,” Krotoszynski said.

Whatever the legality of the Alabama Supreme Court order, same-sex marriage itself appeared to be legal in Alabama, under Granade’s ruling. On March 13, Judge Hall went ahead and granted Shrie and Kirsten Richmond’s petition for an uncontested divorce on the state grounds of “incompatibility of temperament.”

“The order was directed to probate judges not to issue marriage licenses,” said Mark McDaniel, a legal analyst for Huntsville TV station WAFF. “The issue then is a divorce case, a same-sex divorce case, before a circuit judge, should the circuit judge sign the divorce. In my opinion, right now they should do that.”

But as for actually getting married in the state of Alabama? “We’re at a standoff here,” University of Richmond constitutional law professor Carl Tobias told the Los Angeles Times. “This hasn’t happened in any other state. I’m afraid that’s where we are and it may not be resolved until the Supreme Court rules in June.”

And so it was…more or less. After June 26, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Americans have a constitutional right to marry someone of the same sex, most Alabama probate judges began issuing licenses to same-sex couples. A few holdouts refused to issue any marriage licenses at all, citing a state law that permitted them to do so.

On Friday, July 24, in Mobile County Probate Court, retired Baldwin County Circuit Court Judge James Reid approved Cari Searcy’s petition to become the other parent of Kimberly McKeand’s son Khaya. In an irony noted by the Mobile Press-Register’s Casey, Reid had been appointed to handle the case by Roy Moore after Mobile County probate judge Don Davis recused himself. “It’s good because I finally have two legal parents,” the nine-year-old told Toner.

Not that Alabamans opposed to same-sex marriage are done. On August 3, while the legislature was in special session to deal with a state budget shortfall, the Senate Finance and Taxation General Fund Committee approved the bill to do away with state-issued marriage licenses altogether. Instead, the Montgomery Advertiser reported, “spouses would file a signed marriage contract at probate offices.”

Stay tuned.