Editor: HANG ZHANG

After the outbreak of COVID-19, we were forced to stay at home, some of us lost relatives, and others lost their jobs. However, life goes on. We all have to think about where life is going after the coronavirus. Amongst the many changes, the most obvious is that women’s situation may not be good.

A Summary of Gender Issues Identified in COVID-19

According to the article ‘the gender gap in COVID-19 mortality in the United Stated’, men accounted for eight percentage points more deaths than women across all age categories during the COVID-19. However, regarding social impact women are more adversely affected by COVID-19.

Both men and women work from home during the outbreak of Covid-19, but women are the one who mainly cares for the family. In addition, schools were closed, and all students stayed home during the pandemic, which meant mothers needed to do more household duties than before.

Based on the article: ‘Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social, and economic indicators, they found that between March 2020 and September 2021, women are more likely to report unemployment (26.0%) than men (20.4%). According to the American Community Survey, women are overrepresented in low-paying jobs in the US. All restaurants and stores were closed during the outbreak, laying off millions of female sales and hospitality workers. Staying at home may sound simple, but things are often much more complicated for women who live with violent partners. According to the domestic violence charity Shelter, calls for help have increased by 25 percent since Covid-19. The more frightening news is that there have been at least 16 domestic violence killings of women and children in the first three weeks of Covid-19.

Policy Recommendations

First, employment and social security should be fairer. The government should encourage female-dominated industries. They should encourage firms that are manage by women with a majority of female employees, involve them in government procurement, and provide preferential finance and credit to help women obtain employment and attain economic independence. Moreover, they can provide unemployed women with free job-transition training. Second, support should provide in the family to alleviate domestic work and stop the violence. Men and women should share family chores, including housework, child care, and elder care. Then, the government could design targeted programs for preventing and suppressing domestic violence, protecting and aiding victims and providing public resources and social assistance.

Consequences without Intervention

The epidemic exacerbates gender inequality and even stalls or reverses the steps we have taken over the last few decades. We need intervention to recover from the COVID-19 recession. If not? Tourism, production, and service industries will have a hard time returning to their pre-epidemic state, resulting in a continued global economic downturn with the potential for a severe financial crisis.

Research Questions

What is the current situation of Chinese female workforce under the circumstance of Chinese government still taking COVID-19 serious and still adhering to its zero-clearance policy? If China’s leader were a woman, would China still be using the same policies to deal with COVID-19? There is no absolute way to prevent the spread and infection of the coronavirus, so we have to live with COVID-19 and what should government and companies to do to make the economy recover under such conditions?

How the COVID-19 impact me

The year I got my acceptance letter from trinity college, the epidemic started. The result was that I took a year off from school, and now I’m 21 years old and only a sophomore in college. In addition, after coming to the U.S., because of China’s zero policy, international flights reduced dramatically in China, and airfares skyrocketed, with the average price reaching 50,000 RMB one-way and only in economy class. So I was faced with either not being able to go home for a long time or paying high fees and being in hotel quarantine for ten days after returning to China.

What do I learned from the research

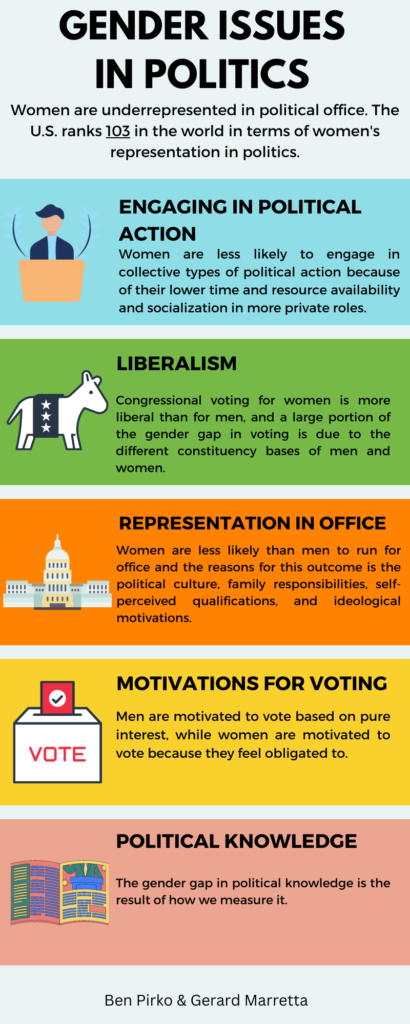

Even before COVID-19, women were still on the wrong side of society. COVID-19 magnifies the unfair treatment of women in society. In the past, I would never look at problems from a female perspective. The concept of women’s rights is vague in China, and many Chinese women do not realize that they are mistreated compared to men because of Chinese educational background. However, there are more serious feminist issues in China than in the United States, with the self-evident “preference for men” at job fairs, the predominance of male leaders in politics and business, and the fact that women are expected to do more of the household work. Unfortunately, in my search for literature on the topic of gender differences of China in COVID-19, this field of research is empty.

Reference

- Bateman, Nicole, and Martha Ross. “Why has COVID-19 been especially harmful for working women.” Brookings [Journal] 14 (2020).

- Albanesi, Stefania, and Jiyeon Kim. “Effects of the COVID-19 recession on the US labor market: Occupation, family, and gender.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 35.3 (2021): 3-24.

- Flor, Luisa S., et al. “Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social, and economic indicators: a comprehensive review of data from March, 2020, to September, 2021.” The Lancet (2022).

- Hennekam, Sophie, and Yuliya Shymko. “Coping with the COVID‐19 crisis: Force majeure and gender performativity.” Gender, Work & Organization 27.5 (2020): 788-803.

- Sevilla, Almudena, and Sarah Smith. “Baby steps: The gender division of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy36.Supplement_1 (2020): S169-S186.