Who published the National School Service and why? For our next class we’ll read a short article by educational psychologist Robert Yerkes, “The Mental Rating of School Children,” National School Service 1, no. 12 (February 15, 1919): 6–7, http://archive.org/details/nationalschoolse01unituoft. Who created this publication and what was its purpose in 1919? What major themes stand out in the February issues? And who made it available for us to view on the Internet today?

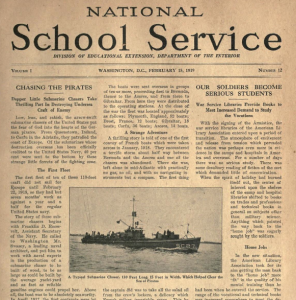

The National School Service was a monthly paper (magazine) produced and distributed by the Division of Educational Extension, in the Department of the Interior of the United States government. This publication was addressed namely to the teachers and educators who had the most impact on the minds of children, but was also available to the public, such as parents of children in the educational system.

Though these monthly issues would seemingly focus on the latest academic developments and teachers who inspire change in the lives of students, the National School Service actually serves a very different purpose. These monthly papers serve as a form of propaganda, promoting nationalistic views of America and informing teachers of the most important aspects of the military…namely, the victories and sacrifices of American soldiers the government wants fed to the minds of youth. Conveniently enough, a very patriotic poem “My Country,” is plastered directly underneath Robert M. Yerkes’ article. That is to say, Major Robert M. Yerkes. Yerkes is not just a psychologist or a scholar, but also a member of the United States Armed Forces.

(Image from http://archive.org/details/nationalschoolse01unituoft)

Robert Yerke’s article within the February 1919 issue of The National School Service suggests a new way to evaluate the mental capabilities of students, thereby classifying them into three groups. By using “the application of mental measurement in the army,” Yerke suggests tracking students in 3 groups: A, B, and C; A completing 5th grade material in 3 years, B in 4, and C in 6. These groups would then separate students into “diverse courses,” funneling A students into a professional track, B into an Industrial track, and C into a manual labor track. Yerke argues that this would be beneficial to students’ intelligence (each student would be able to work at their own level without being pushed or held back), and would provide equal opportunities for children of families in all classes.

(Image from http://archive.org/details/nationalschoolse01unituoft)

This issue was published in February of 1919. Though World War I had just come to a close, the Red Scare was just beginning to take root in society. Furthermore, soldiers were returning from war and had extreme difficulty finding jobs. Interestingly enough, a front-page article of this issue is entitled, “Our Soldiers Become Serious Students,” and another article, “Special Message to Teachers” emphasizes how this month it is imperative that teachers stress the extreme importance of staying in school to their students. This push to both keep kids in school and send retuning soldiers back to school shows how desperate the government was to produce a highly intelligent youth after such a devastating war. Furthermore, it illustrates the lack of job opportunities that currently exist, or jobs that the government feels “may lead him nowhere.” These are most likely the manual labor jobs that Yerke’s “group C” kids would be tailored for.

(Images from http://archive.org/details/nationalschoolse01unituoft)

These National School Service issues were made available online by the Internet Archive, an incredible resource housing millions of primary sources online, and giving multiple means of locating past information on the internet. However, these issues were posted on this database by The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education in Toronto, Canada. I found this curious, seeing how The National School Service was an American produced paper. The information that I needed to answer my questions were located within the text of the February 1919 issue and I was able to reach conclusions through my own historical knowledge of WWI and the Red Scare. However, I wanted to further investigate why these magazines were made available by a Canadian library, and where, if anywhere, could I find the magazine in the archives of the United States government.

(Image from http://archive.org/details/nationalschoolse01unituoft)

I was surprised and alarmed upon realizing that the government has done a very keen job at making The National School Service papers disappear from American history. Not only was I not able to find the works through any of Trinity’s library resources, but I was also unable to find references to the issues on academic search engines such as JSTOR.

Though the National School Service is not directly available through Trinity resources, Trinity does offer, through WorldCat, multiple resources to locate an issue.

(Image from http://trincoll.worldcat.org/title/national-school-service/oclc/1759403)

Blame it on my generation…but I was extremely narrow-minded in my thought process of: If I can’t find something online with ease, it must either not exist, or those controlling the internet must be hiding it! However, copies of the National School Service are conveniently located in many libraries (yes, with actual books….yikes!) around the country.

It was only through a search for Yerkes (not the magazine itself) on JSTOR that I was able to find, “The Handbook of private schools” written by Porter Sargent. This book mentions Yerke’s study on the mental measurement of students as found in the National School Service, though this was the only place in which I could find any proof that such an issue even existed.

Though the above statement is no longer accurate, I think that the passage within Porter Sargent’s “The Handbook of private schools” does a nice job of summing up Yerke’s article.

.

(Image from http://archive.org/details/nationalschoolse01unituoft)

Upon searching the National Archives at www.archives.gov/education, no record of “The National School Service” was found. Clearly, America is ashamed of the propaganda this paper promoted.

It is true that through a search of the national archives online I was not able to locate any issue of the National School Service. However, that is why the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education is so important. This library has utilized their time, resources, and funds to prioritize the online availability of the National School Service, and as scholars, we must be grateful for such accessibility to a document that reveals so much about our country’s past education system.

Good detective work on the publisher and pro-American tone of this 1919 education periodical, which vivid examples from the text. But the claim that US government was “ashamed” or “hid” this periodical is not supported. To the contrary, a WorldCat title search revealed that at least 34 libraries (nearly all in the US) hold this item on their shelves. See http://trincoll.worldcat.org/oclc/1759403 and click on “availability.” The more important point is this: just because a library owns an item does not necessarily mean that they have the funds or have prioritized digitizing it for the web. We’re fortunate that the OISE library in Toronto spent the resources to upload for the rest of us.

Great to see how you revised your post in a way that allows readers to view your prior response (and how it changed), and for crediting the Canadians for digitizing this US government periodical.