Question: What caused the narrative of the Supreme Court’s doctrine with regard to school choice and voucher programs to change from its initial ruling in Everson v. Board of Education (1947) to Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002)?

As the nature of the public school system is rapidly changing in the 21st century, school choice plans have become more and more commonplace. These programs naturally impact those religious academies (predominantly being Catholic schools) that served as the traditional counterpart to the public school system, and the Court has articulated a series of changing arguments with regard to how the government can and cannot aid religious academies. The triangle of public schools, religious academies and government funding has always created establishment clause concerns, and the Supreme Court has been called upon to resolve these constitutional questions, beginning in 1947 with its landmark incorporation of the establishment clause to the states in Everson v. Board of Education of Ewing, NJ (330 U.S. 1). The narrative of the court’s doctrine has changed over time with regard to school choice, and investigating the stimuli behind the court’s changing views with regard to voucher programs, school choice, reimbursement programs, etc. and religious academies can show why the court has granted increase deference to educational policymakers in the 21st century. When evaluating programs of school choice, the Court must weigh facilitating the individual freedom of parents to decide how to educate their children with the constitutional prohibition of government directly aiding or meddling with religion and religious organizations (Minnow 816). Looking at the full text of the court’s opinions and dissents, along with a discussion of changes in educational policy, can show why the court has increasingly ruled to uphold programs of school choice, even when squared against the establishment clause. In the 21st century as problems associated with the nation’s public school system grew increasingly pressing, the court has granted greater leeway to policymakers in using religious academies as parts of voucher or school choice programs. The increasingly compelling state interest in ameliorating public schools have certainly resulted in the Court granting increased deference to educational policymakers, but the partisan shifts to the right on the nation’s highest legal bench from Everson to Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002) have been the deciding factor in changing the narrative of the Court’s legal doctrine. While grating greater policymaking “slack” to those in the educational field may be an auxiliary factor, the dominant factor has been the addition of justices who envision the “wall of separation” between church and state as being shorter than some of their colleagues from the mid-to-late of the 20th century. In the end, some regard indirect aid to religious institutions as unconstitutional, while other jurists see indirect as a matter of private choice.

The court first began asserting the establishment clause with regard to such programs in Everson, when the court held that Ewing, NJ’s use of township monies to compensate the transportation costs for parents who send their kids to religious academies did not constitute a 1st Amendment violation. The opinion of the court, written by Justice Hugo Black – an ex-Klansmen appointed by Franklin Delano Roosevelt who would become one of the constitution’s strongest textural defenders – incorporated the Establishment Clause to the states and used Thomas Jefferson’s metaphor of a “wall of separation between church and state” to guide future cases concerning government establishment of religion (330 U.S. 15, Feldman 65). Black believed that the government had a compelling interest in using taxpayer monies to provide fire and police protection, sewer lines and other services to religious organizations and schools, and that remunerating student transportation costs served the interest of student safety and was analogous to the aforementioned programs (330 U.S. 17-20). Furthermore, since the township’s compensation program gave the reimbursement to parents and not the religious organizations themselves, the aid to religion was even more indirect than police protection, sewer lines, etc. The first dissent in the case, written by Justice Robert Jackson, stated that the program itself did not pass Black’s own “wall of separation” standard, and that taxpayers only assume the responsibility of paying for public schools. Justice Rutledge’s separate dissent stated famously that “Certainly the fire department must not stand idly by while the church burns (330 U.S. 61). Nor is this reason why the state should pay the expense of transportation or other items of the cost of religious education.” The case was decided by a divisive 5-4 vote, and the dissents proved to be more influential in later cases like Lemon v. Kurtzman and Flast v. Cohen. In Everson, the court upheld the transportation compensation program as indirect aid to religious organizations, and as being within the compelling interest of the state to provide for public safety. The most influential aspect of Everson however, was its incorporation of the establishment clause to the states, which would allow for future judicial review of state programs that might offend the 1st amendment (330 U.S. 18).

After the Court’s ruling in Everson, state governments and Congress began initiating programs that were seen as indirectly aiding religious academies, or aiding them in a secular manner. Such was the intent behind Pennsylvania’s Nonpublic Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1968, a statute which used taxpayer dollars to supplement salaries for teachers of secular subjects within private schools, including religious academies (403 U.S. 606-612). The Court had changed too, with the addition of liberal justices William Brennan, Byron White, Thurgood Marshall and Harry Blackmun to the high bench. Alton J. Lemon, a resident of Pennsylvania sued challenging the statute as violating the establishment clause. When the case, Lemon v. Kurtzman, reached the high court in 1971, it was consolidated with a case challenging the constitutionality of a similar program in Rhode Island. Almost a quarter-century had passed from the court’s landmark ruling in Everson, and the nation’s educational system, while not perfect by any means, was not yet suffering from the salient problems that would later drive considerable media, legal and constitutional attention. When the court issued its ruling in Lemon, it struck down the Pennsylvania and Rhode Island statutes as violating the establishment clause. The opinion of the court, written by Chief Justice Warren Burger, a Richard Nixon appointee and conservative jurist, articulated a three-pronged standard that still guides Supreme Court doctrine. Quoting from Chief Justice Burger’s opinion, “First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion…finally, the statute must not foster ‘an excessive government entanglement with religion’” (403 U.S. 602 612-613). If a statute failed any of the three prongs, it would be invalidated. Burger stated that the Pennsylvania and Rhode Island statutes served secular interests in promoting the teaching of secular subjects, and were offered to all private academies regardless of what faith they aligned with, so it satisfied the religious neutrality prong of the test. What created the establishment clause violation Burger stated, was that government would have to monitor whether the funds went only to the teaching of secular subjects, so it violated the famous “excessive entanglement” prong of the test.

The two legislatures, however, have also recognized that church-related elementary and secondary schools have a significant religious mission, and that a substantial portion of their activities is religiously oriented. They have therefore sought to create statutory restrictions designed to guarantee the separation between secular and religious educational functions, and to ensure that State financial aid supports only the former. All these provisions are precautions taken in candid recognition that these programs approached, even if they did not intrude upon, the forbidden areas under the Religion Clauses. We need not decide whether these legislative precautions restrict the principal or primary effect of the programs to the point where they do not offend the Religion [p614] Clauses, for we conclude that the cumulative impact of the entire relationship arising under the statutes in each State involves excessive entanglement between government and religion” (403 U.S. 602 613-614)

While what was or was not “excessive entanglement”, or what kind of entanglement could be defined as “excessive” made the Lemon Standard an inherently vague piece of legal doctrine, but it has held sway in establishment clause cases from its birth in 1971 to present day cases like Hosanna-Tabor v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2012). What distinguished the case from Everson however, was what Justice Brennan called in his concurring opinion a “case of direct subsidy” since the monies went directly to the religious institutions in question (403 U.S. 653). Since the funds went directly to the religious organizations, the government would have to “foster an excessive entanglement” to make sure that they did not advance any sort of religious teaching. While the government may have been able to aid secular subjects in a separate hypothetical situation where it would be easy to monitor the strictly secular use of the funds, the facts of the case distinguished it enough for the two statutes to be invalidated by an 8-0 vote (with Justice Marshall abstaining). Ultimately, the “excessive entanglement” prong would prove vague in future Court doctrine, but here it provided a clear legal impetus for the invalidation of the programs in question. The addition of liberal justices to the Court from Everson to Lemon certainly served as an important factor in the invalidation of the statutes. While the conservative Chief Justice Warren Burger authored the standard in Lemon, the clear and impactful support of left-leaning jurists like Justice Brennan surely had a strong impact on the resolution of the case. Ultimately, Justice White set the stage for the future in his partial concurrence, stating

“Our prior cases have recognized the dual role of parochial schools in American society: they perform both religious and secular functions. See Board of Education v. Allen, supra, at 248. Our cases also recognize that legislation having a secular purpose and extending governmental assistance to sectarian schools in the performance of their secular functions does not constitute “law[s] respecting an establishment of religion” forbidden by the First Amendment merely because a secular program may incidentally benefit a church in fulfilling its religious mission. That religion may indirectly benefit from governmental aid to the secular activities of churches does not convert that aid into an impermissible establishment of religion.” (403 U.S. 663-664)

The impact of Justice White’s concurrence cannot be understated. The notion that religion can indirectly benefit from government aid may not seem like anything outlandish. After all, it is the logical conclusion of Justice Black’s opinion in Everson. While the program in Lemon benefited secular and religious schools equally, the aid was seen as more direct, which would require the sort of “excessive entanglement” the Court feared. Ultimately, the Court did not attack the notion of indirect benefits to religious institutions not being unconstitutional, and precedent set in Everson in that regard would rear its head in future decisions.

After Lemon, Chief Justice Burger’s three-pronged standard faced tough tests in several cases, but was still used as the legal maxim as late as 2000 in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe. Earlier in 1997 however, the Court had stated that the third prong of the test, “excessive entanglement” did not apply to school funding programs. The case, Agnostini v. Felton (521 U.S. 203), invalidated the third prong and further strengthened the case for the constitutionality of programs that indirectly aid religious institutions. While Agnostini can be considered a landmark case in its own right, its use as precedent in the Court’s 2000 decision in Mitchell v. Helms (530 U.S. 793), is extremely important. The opinion of the Court in Mitchell, written by conservative Justice Clarence Thomas, upheld a program that loaned school materials (like textbooks) to secular and sectarian institutions because the aid went to serve the needs of students, as opposed to schools. Since where their children went to school was determined “only as a result of the genuinely independent and private choices of individuals.” – citing Agnostini in affirming the statement – the aid to religious academies was indirect, and ergo constitutional, even when squared with the Establishment Clause (530 U.S. 810). The doctrine regarding indirect impacts on religious institutions, first detailed by Justice Black, had been amplified by the addition of Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, Anthony Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor and the elevation of William Rehnquist to Chief Justice. In the twenty-one years following Lemon, four conservative justices were appointed the Court, and the Court’s doctrine changed in a variety of fields of law, including school choice and the Establishment Clause. Mitchell is an important case in its own right, just as Agnostini certainly is, but it served an important role as a legal facilitator for the Court’s landmark foray into efforts to reform the nation’s failing schools in 2002.

The Court’s monumentally important decision in Zelman v. Simmons Harris (536 U.S. 639), the most important Establishment Clause case of the Rehnquist Court era, was saw the affirmation an important legal doctrines. The opinion of the Court, written by Chief Justice Rehnquist, stated that the final destination of government aid does not impact a program’s constitutionality if citizens make “true private choice[s]” in determining how the assistance (monetary or otherwise) is used (536 U.S. 650). The case divided the court along ideological lines, with the five conservative justices (Rehnquist, Thomas, Kennedy, O’Connor and Scalia) opposing the weakened liberal wing composed of Justices David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, John Paul Stevens and Stephen Breyer. The Court in Zelman set a new five-pronged test to further weigh programs of school choice or others that indirectly aided religious institutions against the Establishment Clause. Following the Lemon Test, the Chief Justice articulated the “True Private Choice” standard, which stated that programs must have a legitimate secular purpose, benefit a wide range of persons, be religiously neutral, include adequate secular alternatives and provide the aid to parents as opposed to the institutions themselves. The background facts for Zelman only serve to cloud the test. Cleveland’s urban schools were among the worst in the nation, and the state of Ohio, with the city of Cleveland, implemented a voucher program that allowed parents to send their children to sectarian institutions – which do a remarkably good job educating inner-city minority students – or private secular institutions if they were below the federal poverty line (Ravitch 116-125). Certainly there was a legitimate secular purpose in ameliorating the city’s failing schools and it did benefit a wide range of impoverished families in Cleveland, but the remaining three prongs divided the court. For one, the liberal justices disagreed with the notion that indirect aid to religious was automatically constitutional, as seen in the dissenting opinions in Agnostini, Mitchell, and Zelman. Secondly, the program in question gave vouchers that amounted to less money than the state gave to public schools on a per-student basis. It almost seemed as if the program was designed specifically to benefit religious institutions. As for the religious neutrality prong of the test, the government aid could certainly find its way to a wide variety of religious institutions as noted by the majority of the Court, but it did have a disproportionate impact on Catholic institutions, a point noted by Justice Breyer in his dissent (538 U.S. 639). Moving to the adequate secular alternatives prong, the justices again remained divided. Justice Souter wrote in his dissent that more than 95% of the participating voucher schools were private, religious academies, which muddled the implementation of the prong. As previously stated, public schools in Cleveland had little incentive to participate, and secular private schools asked for far greater amounts in tuition money than the voucher offered, and few had open seats available (539 U.S. 639). While the conservative wing of the court believed there were adequate nonreligious options, the liberal justices aptly countered by noting, again, that more than 95% of the participating schools were religious schools. The last prong of the test, concerning indirect aid, similarly divided the Court. While there are specific liberal/conservative differences in opinion regarding indirect aid, the vouchers were given to parents, but the money itself was given directly to religious institutions. The conservative justices likened it to a tax credit, if a citizen receives money back on their taxes and donates some to his church, it should not be an Establishment Clause violation. The liberal justices however, were concerned with the fact that the vouchers were given to schools by the parents, but the money itself was given directly from taxpayer funds to the institutions themselves.

Ultimately, the Court’s opinion in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris was highly divisive. In addition to the fact that the programs were upheld by a 5-4 vote, the case produced six separate opinions, further evidence that the Court’s membership could not agree on a single legal conclusion regarding the constitutionality of the voucher program. The end result of Zelman however, was the affirmation of the principles outlined by Hugo Black in Everson. When the government indirectly aids religious schools, and when parents make private choices in where and how that aid is used, the programs are upheld. It is clear from the opinions of the Court’s conservative justices however, that these programs are being upheld not as an act of deferring to local and state educational policymakers, but rather because they see Thomas Jefferson’s “wall of separation” as being far shorter than their liberal colleagues. In an alternate metaphor, programs of “true private choice” that give indirect harm can also be seen as a door allowing the Court to uphold them.

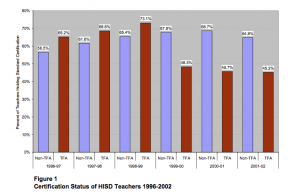

The problems plaguing the nation’s public schools are great in number, size and scope, and the Court’s decision in Zelman certainly enlarged the toolbox available to policymakers, but the motivation behind the Court’s ruling does not lie in aiding educational policymakers. Instead, it is simply a side effect of the Supreme Court’s ideological shift to the right, especially in the eras of the Burger and Rehnquist Courts. There is no evidence in the Court’s many opinions in these cases to support a the conclusion that the Court has lowered the wall with the express purpose of aiding educational policymakers. The Court’s lowering of the wall of separation is primarily driven by an ideological interpretation of the Establishment Clause that tolerates government aid to religious schools, institutions and affairs. The key factor behind the changes in Court doctrine lie in the changes in its membership. From Everson to Lemon, five liberal and two conservative justices were added to the Court (joining two liberal justices who remained on the high bench), and from Lemon to Agnostini, Mitchell and Zelman, five conservative and four liberal justices were added. Ultimately, the narrative of the Court’s doctrine regarding school funding, voucher programs and school choice has been parabolic, moving to uphold such programs in Everson, striking them down in the Lemon era, and again moving to keep them in place as the Court shifted to the right in the late 20th and early 21st century. The primary cause of the parabolic nature of the Court’s doctrine however was not a desire by the Court to give education policymakers greater deference, but rather was caused by shifts to the political right among its membership.

Works Cited

330 U.S. 1 (1947) Everson v. Board of Education of Ewing, NJ

403 U.S. 602 (1971) Lemon v. Kurtzman

521 U.S. 203 (1997) Agnostini v. Felton

530 U.S. 793 (2000) Mitchell v. Helms

539 U.S. 639 (2002) Zelman v. Simmons-Harris

Feldman, Noah. Scorpions: The Battles and Triumphs of FDR’s Great Supreme Court Justices. New York: Twelve, 2010. Print.

Minow, Martha. “Confronting the Seduction of Choice: Law, Education, and American

Pluralism.” Yale Law Journal 120 (2011): 814-48. The Yale Law Journal Online.

Yale University, Jan. 2011. Web. 2 Apr. 2012. <http://yalelawjournal.org/the-yale-law-journal/feature/confronting-the-seduction-of-choice:-law,-education,-and-american-pluralism/>.

Ravitch, Diane. The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing

and Choice Are Undermining Education. New York: Basic, 2010. Print.

According to the school’s student run newspaper The Wesleyan Argus, the college’s first African American student Charles B. Ray attended the institution for seven weeks in the fall of 1832 after harsh racist acts he dealt with from white (mostly southern) students (Argus, par. 1). These students pleaded with Fisk to expel Ray; some even threatened to withdraw their attendance from the school. After Ray’s withdrawal from the school, the board of trustees at the time passed a resolution that stated “None but white male persons shall be admitted as students at this institution” (Argus, par. 1).

According to the school’s student run newspaper The Wesleyan Argus, the college’s first African American student Charles B. Ray attended the institution for seven weeks in the fall of 1832 after harsh racist acts he dealt with from white (mostly southern) students (Argus, par. 1). These students pleaded with Fisk to expel Ray; some even threatened to withdraw their attendance from the school. After Ray’s withdrawal from the school, the board of trustees at the time passed a resolution that stated “None but white male persons shall be admitted as students at this institution” (Argus, par. 1).